Natalia Zavalonkova, a former history teacher from Mariupol, Ukraine, has been staying at the PTAK Expo Center in Warsaw, Poland, for two months.

The center, which usually hosts large trade fairs and conferences, has served as a temporary shelter for Ukrainians fleeing the war since February of 2022. Inside one of the noisy, cavernous buildings, rows of camp beds are lined up side by side.

Zavalonkova is one of about 800 Ukrainians currently staying there. She carries her possessions with her in a small plastic bag at all times because she said she is afraid they will be stolen.

The center includes a medical facility, a veterinary office and a kids’ playroom. The space was intended as a temporary stop-gap for refugees arriving from Ukraine, but some of its residents have been there for weeks — sometimes months.

Starting March 1, Ukrainians staying in state-funded accommodation like this one for longer than 120 days will have to pay 50% of their housing and food costs. After six months, that goes up to 75%.

When Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24 last year, Poland opened its borders, promising millions of fleeing Ukrainians access to the Polish labor market, as well as health and social benefits.

Almost 10 million Ukrainians have crossed the Polish border in the past 12 months with more than 1.5 million staying on in Poland.

The country’s welcoming attitude has garnered much praise. US President Joe Biden on a recent visit to Warsaw said, “Poland’s generosity, your willingness to open your hearts and your homes, was extraordinary.”

Surveys show about 70% of Poles offered assistance to fleeing Ukrainians in the early months of the war and in 2022, Poland was estimated to have spent $8.3 billion on housing, health and other services for Ukrainians, the highest in Europe.

But prior to the war in Ukraine, the Polish government’s treatment of migrants and refugees was far from warm.

In 2021, it imposed a state of emergency at the country’s border with Belarus to prevent migrants and asylum-seekers, many from Syria and Afghanistan, from crossing into Poland.

In January 2022, authorities began construction of a 186-kilometer wall on its northern frontier to deter migrants. In November last year, the Polish government said it wanted to lower the cost impact of new Ukrainian arrivals.

Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said the rules would be changed on March 1, “so that Polish taxpayers have to pay as little as possible for this potential next wave.”

Anna Chmielewska, coordinator of the Help Center for Foreigners with the Ocalenie Foundation, one of the main refugee support organizations in Poland, said the new policy is already having an impact.

“When people got information that they’re going to have to pay for the accommodation, some of them decided to go back home to Ukraine, because they know that they won’t be able to pay,” she said.

There are exceptions to the new rules; those unable to work because of their age or disability will be excluded, as well as pregnant women and mothers of three or more children. But Chmielewska said the exemptions fail to take into account the varied circumstances of Ukrainian refugees, most of whom are women and children. Chmielewska wonders how a single mother can be expected to look for work with no child care in place.

She believes the government’s plan is less a cost-saving measure than a political stunt.

Poland holds a general election later this year and polls show the ruling Law and Justice party currently commands about 30% of the public vote. The government will do what it can to boost that result, she said.

Not all nongovernmental organizations oppose the policy.

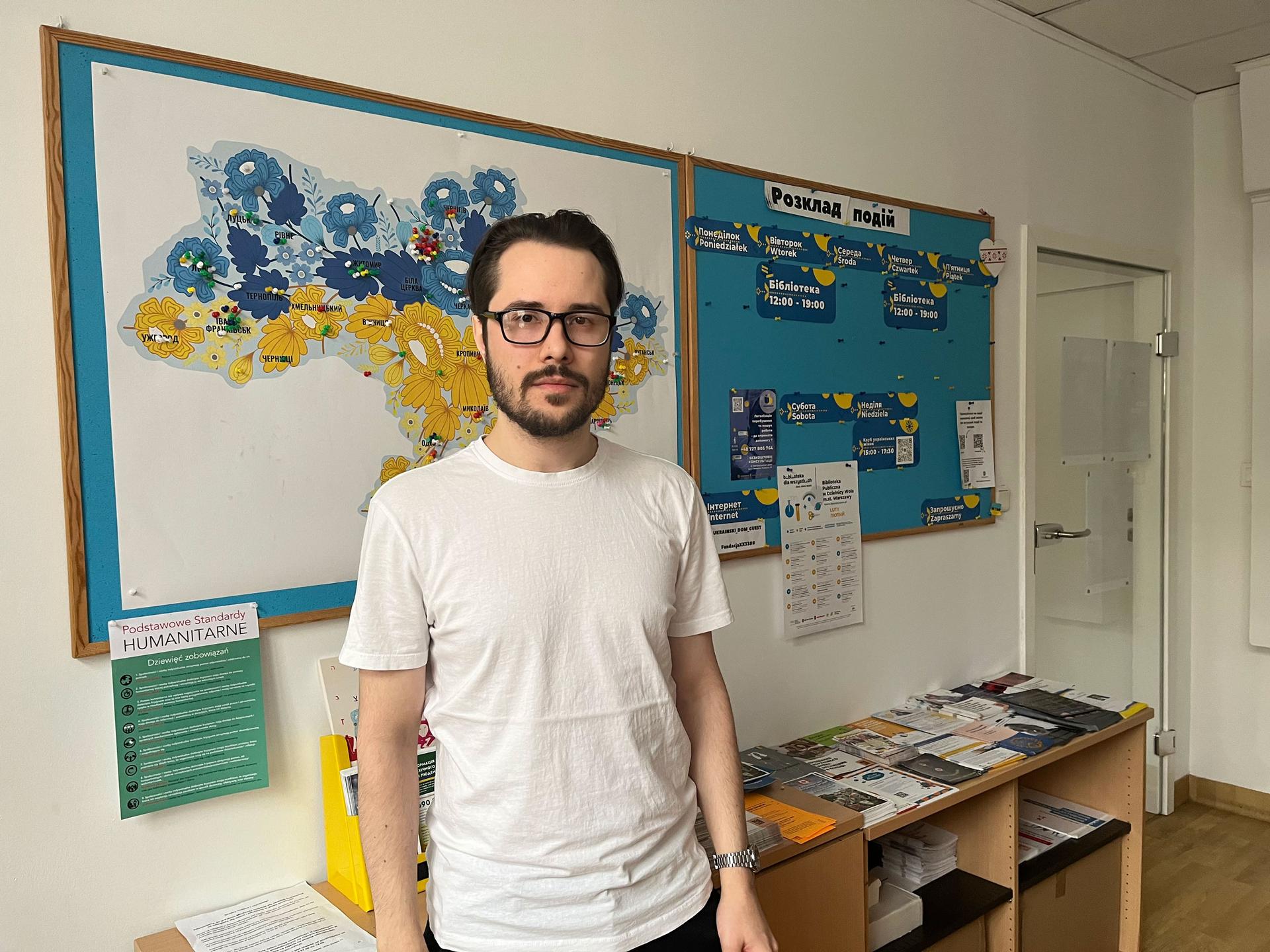

Dmitri Bilecki, a housing department employee at The Ukrainian House, a crisis response center that sources accommodation for Ukrainians arriving in Poland, said the Polish government cannot be expected to cover the cost indefinitely.

Bilecki believes the new charges might serve as an impetus for Ukrainians to find a job in Poland.

“They need to start finding a way to get themselves together in such a way that they can start to plan their lives,” he said.

Some Ukrainians are reluctant to look for work because they are hoping the war will end soon and they can return home, but this is not necessarily the case, he said.

Many Ukrainian refugees are now employed in Poland, with the number of foreign workers registered in the country’s social insurance system increasing by 22% in 2022.

Bilecki said there is work available, but the jobs may not meet standards they’re used to because of their lack of Polish-language skills.

Chmielewska also said that some refugees are still processing the trauma of the war. People often need psychological support before they can even consider looking for a job, she said.

The government’s policy is intended to move Ukrainians out of state-funded accommodation as soon as possible and into the private rental sector. But the rental market, particularly in large cities like Warsaw, is under tremendous pressure.

The sudden surge in the capital’s population in the last year has driven up demand. Ukrainians now make up more than 3% of Poland’s 37.8 million population. Inflation, high energy prices and opportunistic landlords have hiked up the fees.

Prior to the war in Ukraine, Poland was already seen as having one of the European Union’s most-challenging housing situations. A survey in 2019 showed almost 50% of young people living in overcrowded households, homeownership stagnating for over a decade and a deficit of more than 2 million dwellings.

Ukrainians trying to rent privately in Poland also face an additional challenge, Chmielewska said.

“There is this kind of atmosphere that it’s better not to rent a flat to a foreigner,” she said. Ukrainians and other foreigners find it difficult to rent here simply because they are not Polish, she said.

Chmielewska said that Poland’s warm reception to Ukrainians was uplifting to witness but she worries that some of that generosity of spirit may be waning.

In late 2022, more than half the Polish population were reported to be supporting refugees out of their own pockets. By January, that figure had dropped to 41%, according to the Center for Public Opinion Research in Warsaw.

The number of Poles offering to volunteer at the Ocalenie Foundation and assist Ukrainian refugees has also dropped in recent months. Chmielewska said all her organization’s volunteer workers are now non-Polish.

Ukrainian teacher Natalia Zavalonkova is hoping to leave the Warsaw Expo Center before her four-month time limit is up and she will be charged to stay. She is waiting on a visa to go to Britain where a woman has offered her a room in her house. They talk on the phone or on Zoom almost every day, she said.

But all Zavalonkova said she really wants is to go back home to Mariupol, and to be near the Azov Sea again.

“I miss the sea,” she said.