Erfan Kudusov runs a restaurant in Kyiv that serves as an homage to Crimean Tatar heritage and identity.

The restaurant feels a little like a museum with its walls covered in photographs, paintings, postcards and other objects of cultural significance.

Kudusov, a Crimean Tatar activist, points to one painting of a stork confined to a golden cage that symbolizes the plight of Crimean Tatars.

“The cage is so tight that the bird can’t even spread its wings,” he said.

It’s been nearly a full year since Russia launched an all-out invasion of Ukraine. Ukrainian leaders say victory will come when the Russians make a full retreat out of Ukraine — including the Crimean Peninsula.

Russia occupied this territory in the southern part of the country in 2014. The Crimean Tatar people, a predominantly Muslim Turkic ethnic group, have called the area their homeland, going back centuries.

And they say their homeland is part of Ukraine, not Russia.

Illegal annexation

In February 2014, Russian troops entered Crimea. Russia staged a referendum vote. Within a couple of weeks, President Vladimir Putin declared that Crimea is part of the Russian Federation.

Nearly the entire international community said the annexation was illegal. But it was a major political boost for Putin, according to Samuel Charap, a political scientist with the Rand Corporation.

“I think Putin has come to view Crimea as an organic part of Russia as much as any other undisputed region. It has this additional strategic importance as the base of Russia’s Black Sea fleet,” he said.

Crimea is a huge part of Putin’s legacy and his current political standing, he added.

For the Ukrainians, it’s simply Russian-occupied territory.

Liberating Crimea

Last month at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, President Volodymyr Zelenskiy reiterated that Crimea was part of Ukraine and that the country would liberate the region.

But retaking Crimea is a calculated military risk, according to Jeffrey Edmonds, with the Center for Naval Analysis in Arlington, Virginia.

“There’s a very tight choke point leading from mainland Ukraine into Crimea,” he said, adding that they would have to go by land because of Ukraine’s limited naval power.

“[The Ukrainian military] can certainly shell the [Crimean] peninsula if [it] got close enough, but it would be very hard militarily to take it.”

“They can certainly shell the peninsula if they got close enough, but it would be very hard militarily to take it,” Edmond said.

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion last year, the US has said it supports Ukraine’s right to defend its territory.

But retaking Crimea by military force is far more complicated. Tension between the US and Ukraine could increase if the US determined that the escalation risks are too high.

“[The US] would continue to assess that if the Ukrainians were in a position to take Crimea,” Edmonds said.

A history of longing to return

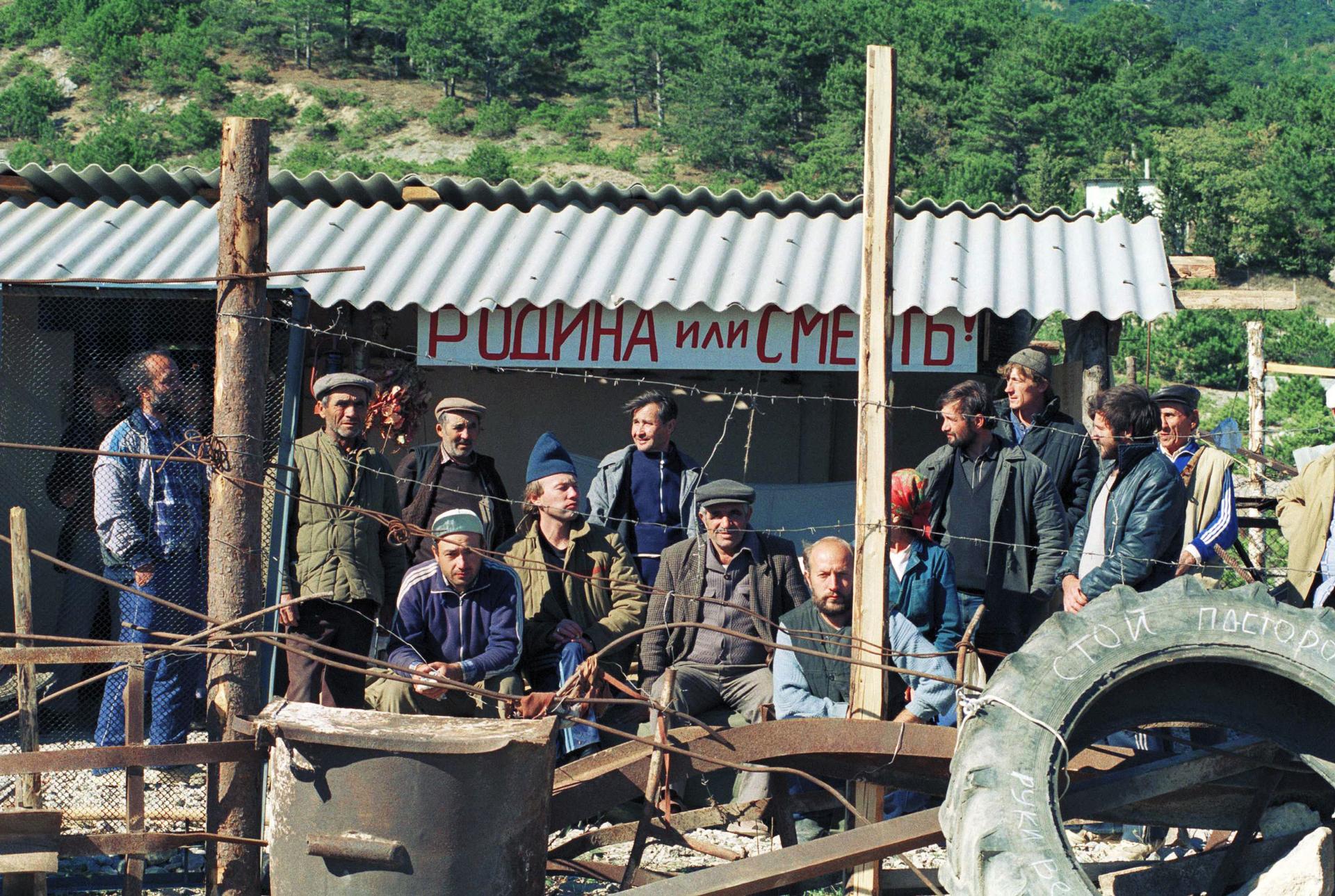

Tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars have lived through forced displacement from Crimea, and have longed to return to their homeland.

In May 1944, as a result of Joseph Stalin’s orders, tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars were deported from Crimea and forcibly relocated to Soviet republics in Central Asia. In the process, thousands of Crimean Tatars died.

“When Crimean Tatars [were] deported in 1944, all [these] Crimean Tatar people, in countries of Central Asia, we [fought for] freedom, and [we] fight for returning to Crimea,” said Tamila Tasheva, a Ukrainian government official based in Kyiv, appointed by President Volodymyr Zelenskiy as the special representative for Crimea.

Tasheva, a Crimean Tatar Ukrainian citizen, was born in Uzbekistan and returned to Crimea in the late 1980s, when she was 5, along with many other Crimean Tatar families. She said that it was a joyful, but also difficult, time.

The government made it almost impossible for Crimean Tatars to reclaim lost property. Buying land and building new homes was also difficult.

Still, tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars resettled in their homeland as the Soviet Union fell apart and Ukraine gained independence.

Life back in Ukraine started feeling normal, but everything changed in 2014, when Russia initially invaded Ukraine and illegally annexed the Crimean peninsula.

Home or freedom

Today, Tasheva’s parents still live in Crimea, in what she calls a “temporary occupied territory.”

Over the last year, Russia has intensified its crackdown on Crimean Tatar institutions and civil society.

Tasheva said that more than 150 Crimean Tatars are now locked up in Russian prisons.

“[The] Ukrainian state [doesn’t] have access to Crimea, but of course we have a lot of communication and connection with our people,” she said.

She and her team are already planning for the eventual liberation of Crimea from Russian occupation.

Back at the restaurant, Kudusov served up chebureki, deep-fried turnovers filled with ground beef or lamb and onions — Crimea’s national dish.

The 54-year-old father of four pointed to the irony that most Crimean Tatars live with these days.

Crimean Tatars living in Ukraine have their freedom but not their home, while those still in Crimea have their home, but not their freedom.

He said his family waited for decades to return to Crimea — and they did, back in the early ‘90s.

Now, once more, he said, he has no doubt that Crimean Tatars driven out by the Russian invasion will return again.

Max Tkachenko contributed to this report.