Back in October 2022, a day before President Xi Jinping was set to assume an unprecedented third term as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, an activist named Peng Lifa made his way to a highway overpass not far from the capital’s tech quarter. He was wearing a construction worker’s outfit and carrying something under his arm.

The Sitong overpass is an enclosed bridge spanning six lanes on what’s known as the Third Ring Road in Beijing. On one side of it is the old Friendship Hotel where, in the time of Mao Zedong, foreigners used to be required to stay. On the other, is one of China’s top institutions of higher learning, Renmin University.

This is where Peng decided to unfurl two banners that, in handwritten Chinese characters, condemned Xi’s “zero-COVID-19” policies.

Say no to COVID testing, yes to livelihood.

No to lockdown, yes to freedom.

No to lies, yes to dignity.

No to Cultural Revolution, yes to reform.

No to great leader, yes to voting.

Don’t be a slave, be a citizen.

Peng’s protest was one of the precursors to the largest street demonstrations in China since 1989, when students gathered in Tiananmen Square to ask for political reform and freedom of expression.

The 1989 demonstrations ended when the Beijing leadership sent in tanks. The latest protests ended when the central government unleashed a digital arsenal that was less deadly, but just as effective. Using human and electronic censors, “safe browsing” filters, GPS tracking and facial recognition software, China managed to defuse national outrage over Xi’s strict COVID-19 policies without firing a single shot.

“I think the key thing the Chinese government sees very differently about protest now versus earlier in its history is that they don’t give movements a chance to dig in,” said Robert Potter, a longtime China watcher and co-founder of threat intelligence company Internet 2.0.

“They’re very much into early intervention, particularly on mainland protests. They are very heavy-handed, very early, and that’s because they fear the huge international fiasco of a major crackdown like they had in 1989.”

That’s not to say people didn’t know about Peng’s banners. Photographs of his lone wolf protest appeared on social media not long after he’d tied his message to the bridge. Pedestrians who had seen the events unfold began sharing videos and Beijing’s censoring algorithms rushed to erase the images from the web. China began limiting hits for search terms like “Beijing” or “Sitong.”

Then ordinary citizens began employing Apple’s AirDrop feature to share the video; chat groups weighed in and began to amplify it too, helpfully offering step-by-step instructions on how to set up VPNs — or virtual private networks — so the curious could share the video on the internet outside China.

People letting off steam

About a month after Peng’s banners vanished from China’s internet, a fire broke out on the upper floors of a high-rise apartment complex in Urumqi, a city in the far northwestern province of Xinjiang. Videos of the blaze popped up on Chinese social media sites like WeChat and Douyin. They showed flames pouring out of windows on the upper floors. Ten people died in the fire; they were all members of China’s Uyghur minority.

News of that fire might have stayed in Xinjiang, were it not for one thing: rumors that filtered out about why the Xinjiang residents couldn’t escape the blaze — people said they were locked inside the building. The central government denied the claims, but locked doors were a feature of President Xi’s “zero-COVID” policy.

In order to keep COVID-19 cases in China to as close to zero as possible, he ordered mass testing, quarantines and lockdowns — and anyone who tested positive for COVID-19 or even had neighbors who tested positive were often physically locked inside their own buildings. In fact, social media was filled with videos of authorities actually welding doors shut. The Urumqi fire became an inflection point: The people’s patience with Xi’s COVID-19 policies had run out — so they took to the streets.

Contrary to popular belief, Chinese leaders actually allow protests to happen quite frequently — even in Xinjiang — as long as they stay local.

“You’ll see large worker strike protests in China regularly. They usually coalesce around an issue specifically where they don’t blame the leadership,” Potter said.

“The traditional narrative is that if Beijing knew, they’d never let this happen, but if protestors stick to localized complaints, they’re generally allowed to protest quite a bit.”

The central government has come to see local street protests as a way for people to let off steam. The citizens have grievances. The government fixes whatever it is, and then life goes on. But the Xinjiang protests weren’t really about a local issue — they were about Xi’s restrictive COVID-19 policies — like the lockdowns that everyone in China had experienced in one way or another.

“I’m surprised protests took as long as they did to materialize,” Potter said.

Disappearing road signs

Just days after videos of the Urumqi fire appeared on social media, people began to gather in a trendy part of Shanghai, holding lighted candles. It was “to commemorate the victims who just burned alive in this fire in Urumqi,” said Rayhan Asat, a Uyghur lawyer in London who watched this unfold in Shanghai.

They had gathered Urumqi Road, one of the bustling thoroughfares in the French concession neighborhood of the city. They laid flowers, sang songs and offered the occasional shout against Xi’s lockdowns. What started as just a dozen people and a spontaneous vigil became a demonstration of hundreds of people hours later. State-backed bloggers blamed the gatherings on foreign “black hands,” and the government vowed to crack down on “hostile forces.”

The next morning, when people returned to Urumqi Road, something was missing: All the street signs that read Urumqi had been removed.

“Little things that could unite people, little things that the government sees as a danger or threat to their power must be eliminated,” Asat said.

“One day it could be [that] a road sign can become a threat to a very fragile and insecure government.”

China’s censorship machine is considered one of the most sophisticated in the world.

Its algorithms and armies of human censors hunt down and delete countless posts on China’s internet every day. And that apparatus went into overdrive after Peng’s banners snapped back into action after the Xinjiang fire.

As thousands of people posted videos of demonstrations, Chinese censors were overwhelmed. It turns out thousands of videos from a variety of angles were much harder for the censoring algorithm to identify than a single video shared millions of times. What’s more, there isn’t one single nationwide system; instead they tend to be regionally controled, which is how so much information on the demonstrations made it out into the world.

“It is a patchwork of systems set up individually, and they primarily act at their best at the local level,” Potter said.

“People shouldn’t see this system as invulnerable or absolute and a guarantee against successful protest and policy change in China. But it also gives protesters a myriad of ways to slip through in ways that can’t be caught.”

In other words, there are ways to trick the system. Flip a demonstration video on its side and the algorithm can’t make heads or tails of what it is. Send a recorded video of videos — that confuses it, too.

Release the spambots

In short order, protest videos from cities all over China appeared on international social media sites like Twitter and Instagram, which are blocked in China. So, the leadership pulled another weapon out of its digital arsenal: spambots, an army of zombie computers that they use to inject irritating content into feeds outside China.

Charity Wright, a senior China analyst at Recorded Future, a threat intelligence company, was watching as these bots inserted themselves into conversations. One minute someone would think they were going to get the latest from the protests in the southern city of Chengdu, and then the next, their feed would fill up with a bunch of ads for escort services or pornography. (“Click Here” and “The Record” are part of Recorded Future News, an editorially independent arm of Recorded Future.)

“They’d hijack the conversation about the protests in China and drown it out with distracting content,” she said. “Not necessarily an alternative narrative, but just a major distraction. The primary objective, we believe, of this campaign, was to drown out conversation on platforms where they don’t have control.”

Type “#Wuhan COVID protests” and instead of information about the demonstrations, there was a solicitation for sex. The hope was that anyone searching for protest information would get so much junk in their feed, they’d give up trying to find the latest news on the ground. Wright said China used spambots to mess with news feeds in Taiwan during its most-recent elections.

Rounding up protesters

While all the censorship and spambots were working in full view, Internet 2.0’s Potter said China’s network of cameras, facial recognition software,and tracking apps was processing the faces of protesters.

The surveillance system was perfected in Xinjiang, where the apartment building fire was in November. Back in 2017, the Chinese government reportedly started arbitrarily detaining Uyghur Muslims, a Turkic-speaking ethnic minority in Xinjiang, putting them in re-education camps. Part of the program included surveillance and forced labor, among other things. The US described what China was doing in Xinjiang as genocide. The UN said they were crimes against humanity. China claims to have closed the camps in 2019.

“Xinjiang, of all the places, is where the latest and the best [technology] usually shows up first,” Potter said.

“And what shows up in Xinjiang usually proliferates eastward across the country, and that gives them the ability to be very effective.”

Rayhan Asat, the lawyer, has seen the surveillance operation at work in Xinjiang. Chinese authorities picked up and detained her brother, Ekpar, back in 2016. He had been a tech entrepreneur, and was detained by authorities after returning to Xinjiang following a prestigious State Department leadership program. He was eventually sentenced to 15 years in prison on suspicion of inciting ethnic hatred.

Asat said the charges and detention came as a complete surprise.

“You could be just minding your own business, walking down the street and a police officer would come to you just to make sure you were not one of the participants in the protests,” she said.

Which may have been what happened to a 26-year-old Beijing-based editor named Cao Zhixin and three of her friends. They had attended one of those candlelight vigils in Beijing for the people in the Urumqi fire.

Last month, a video she recorded of herself surfaced on the internet. “If you are watching this video,” she tells the camera, “I have been taken away, like my other friends.” The video is a close-up of her face: She has shoulder-length hair and bangs and looks younger than 26.

She said she and her friends had protested peacefully to support the people in Urumqi. “We respected public order and didn’t have any conflict with police,” she tells the camera, “so why do you still have to secretly take us away?”

Cao and three of her friends are thought to be among the first people rounded up for taking part in the protests that happened in Beijing. Human rights organizations say that the police asked the young women about their book club and their reading list, which was apparently filled with feminist works viewed by Chinese authorities as bad and smacking of foreign influence. Reportedly, Cao was asked about her use of the messaging platform Telegram; it is blocked in China, and police have been stopping people on the street to see if the app is on their phones.

Journalists and human rights organizations have been trying to publicize the cases of Cao and her friends. As of this writing, it is unclear where they are.

Rice paper flyers

Zhou Fengsuo’s experience could be instructive. He was a student leader in Tiananmen Square in 1989, and he also disappeared. Zhou was a physics major at Tsinghua University at the time and a member of the Standing Committee of the Beijing Students Autonomous Union, the student group that led the 1989 protests.

He helped organize and inspire the millions of people who took to the streets in dozens of Chinese cities in hopes of winning political reform and free speech in China. This was before the internet, before email and before social media apps could rally the masses. The Tiananmen protests ended when soldiers and tanks rolled into the center of Beijing on June 4, 1989.

Zhou said he was among the last of the Tsinghua students to leave before the tanks came in, and he remembers the student leaders had a debate about a key component of their communications system before leaving the square.

“I was part of the rear guard,” he said recently.

“When we were leaving, we had a debate about whether we should carry the copy machine out. It was the best one we had.”

Actually, it was a mimeograph machine — one would scratch something out on a kind of carbon paper, attach it to a drum, ink it up and then make lots of copies by turning a handle. It is about the same size as a desktop printer and quite a bit heavier.

“I believe we carried it back,” he said. Authorities eventually arrested Zhou a short time later, and he spent a year in a Chinese prison and then was released. He left China a short time later.

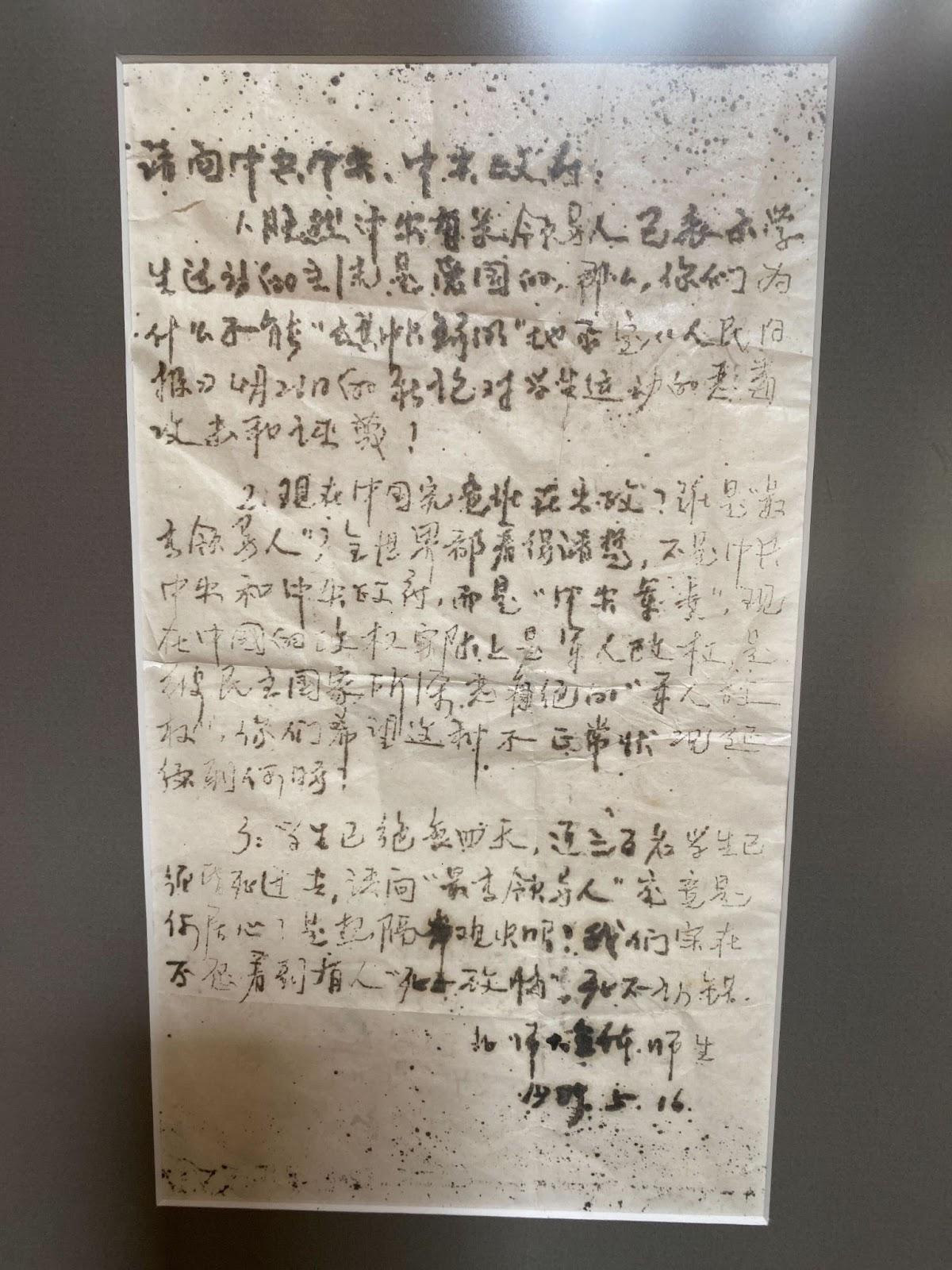

I have one of the flyers that Zhou’s machine was likely churning out that summer of 1989. I remember when I got it. I was in the square and someone handed me a piece of rice paper. The ink was still wet and I remember bringing it up to my nose — it smelled of kerosene.

The students used kerosene to thin the ink so it would go farther. I folded the flyer up, put it in my bag and only found it more than a year later. They were the students’ first three demands of the Chinese leadership. They were listed in neat handwritten Chinese characters. I showed it to Zhou and he smiled, and nodded. “Excellent. Beautiful,” he said. “These are precious today.”

And, ironically, much harder to censor.

An earlier version of this story originally appeared in The Record.Media. There was additional reporting by Sean Powers and Will Jarvis.