Despite lack of govt loans for college in Cambodia, these students are making it work

Srey Touch Kroch stood over a large wok, frying pieces of chicken in hot, bubbling oil as she cooked a Cambodian dish called cha kreung satch moan for 40 people.

The second-year student at the Royal University of Phnom Penh is studying international business management, and it was her turn to make dinner for the women she shares a dorm with.

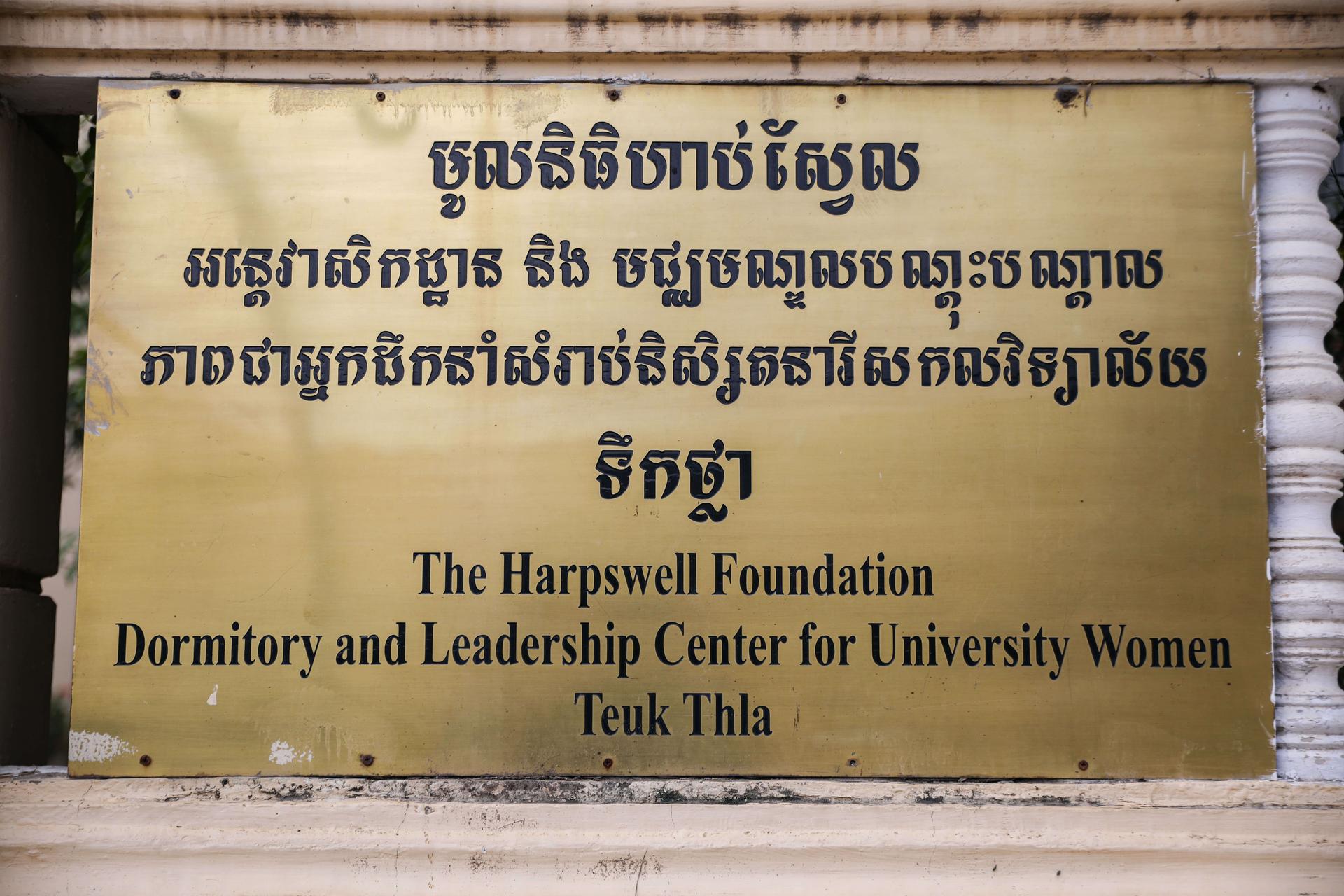

The students’ housing and food are paid for by Harpswell, a US nonprofit that raises money from donors and also has staff in Cambodia. The program opened its first dorm there in 2006. Kroch and the other women say they are grateful to live in a residence hall and pursue a university degree.

Only about 20% of Cambodians complete the 12th grade, according to a 2021 report from Cambodia’s Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport. Overall, only around 10% of college-aged youths are enrolled in university.

Dorms are not common, and students generally live with families or rent an apartment. Without free housing, many of these students from poor rural areas would not be able to attend university in the capital.

“It would be another burden for my family because they would have to pay for my school tuition, my place to live and also for other financial support that I would need to ask for coming to Phnom Penh,” Kroch said.

Education in Cambodia was decimated during the Khmer Rouge’s rule in the 1970s, in which educated people were targeted. Following the genocide under the regime, public universities reopened and private institutions formed beginning in the 1990s. While Cambodia has built up its higher education offerings since then, the government puts less toward university funding than most other countries in Southeast Asia.

Students from rural areas have a particularly hard time managing the costs. Farming incomes have become less sustainable for supporting families, and while public universities charge about $500 in tuition a year, that’s out of reach for most rural Cambodians.

There is little support from the government, and the portion of education funding going to universities fell by half after 1990. The government does offer scholarships for about 15% of enrolled students at public universities.

But the living stipends provided are not adequate, said Bunhorn Doeur, a PhD candidate studying education at the University of Southern Queensland in Australia. He knows firsthand how hard it is to live in Phnom Penh on a student’s budget.

“It’s impossible for them to live in the capital city with that allowance. It’s only about $10 to $20 a month,” he said. “There is no way that they can live depending on those funds at all.”

Student loans are not really an option in Cambodia. The country does not have a public student loan program, although the Education Ministry has said it plans to set one up by 2030. Interest rates charged by private banks are as high as 18%.

Plus, many families are already deeply in debt. The World Bank called Cambodia’s ratio of household debt to gross domestic product “exceptionally high,” more than three times the rate of countries such as Sri Lanka and Indonesia. The average microloan in 2020 was around $4,200, more than the annual income of 95% of Cambodians, according to a report from the human rights groups Licadho and Equitable Cambodia.

A lot of students from rural backgrounds have to find creative ways to get through university. For Sroem Khen, a child of farmers from Kampong Cham province, that meant becoming a monk at the age of 15, which is not particularly uncommon.

“One day, I decided that if I don’t become a monk, maybe I cannot continue my education at that time, because our financial situation was not very good,” he said.

Buddhism and education are deeply intertwined in Cambodia, and many pagodas in Phnom Penh house male university students from the provinces.

“We got a free place to stay. The pagoda I stayed at was very good because we were provided one room each and then two meals per day,” he said, adding that the pagoda gave him a lot of support.

Khen eventually graduated from university, left the monastery and now has a job with a corporate training company. But in his spare time, he runs a program working with students attending a Buddhist high school, preparing the next generation for college.