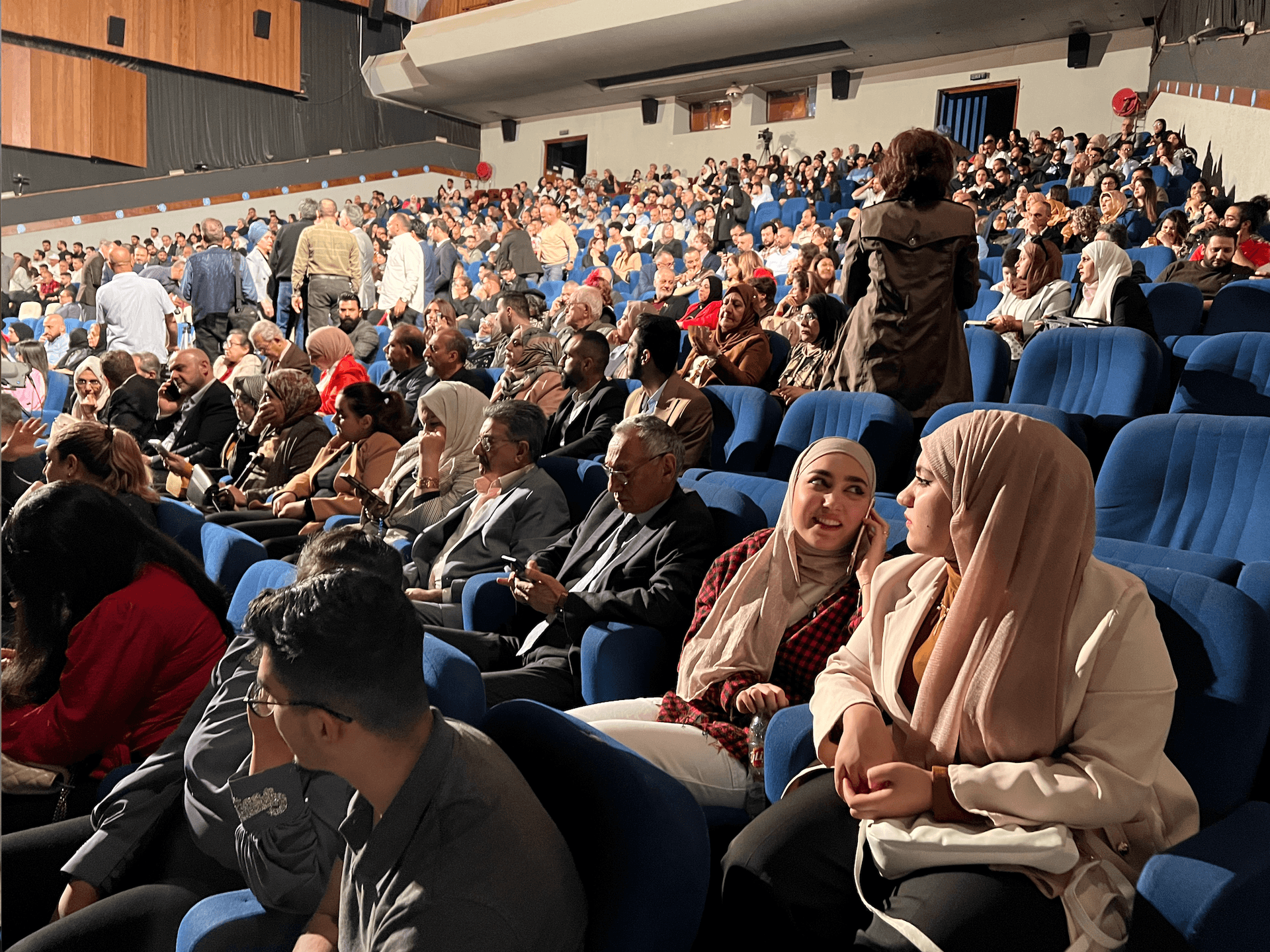

On a Saturday evening in March, the sound of music by French composer Camille Saint Saëns filled the halls of the National Theater in Iraqi capital of Baghdad.

Renowned cellist and conductor Karim Wasfi led the performance to a packed auditorium. Iraqis — young and old, men and women, hijabi and non-hijabi — had come to spend an evening filled with music.

Music has had an important place in Iraqi culture throughout history. But years of war, sectarian violence and the rise of ISIS disrupted performances and forced many of the country’s musicians to flee.

Now that Iraq is relatively calmer, music is thriving once again.

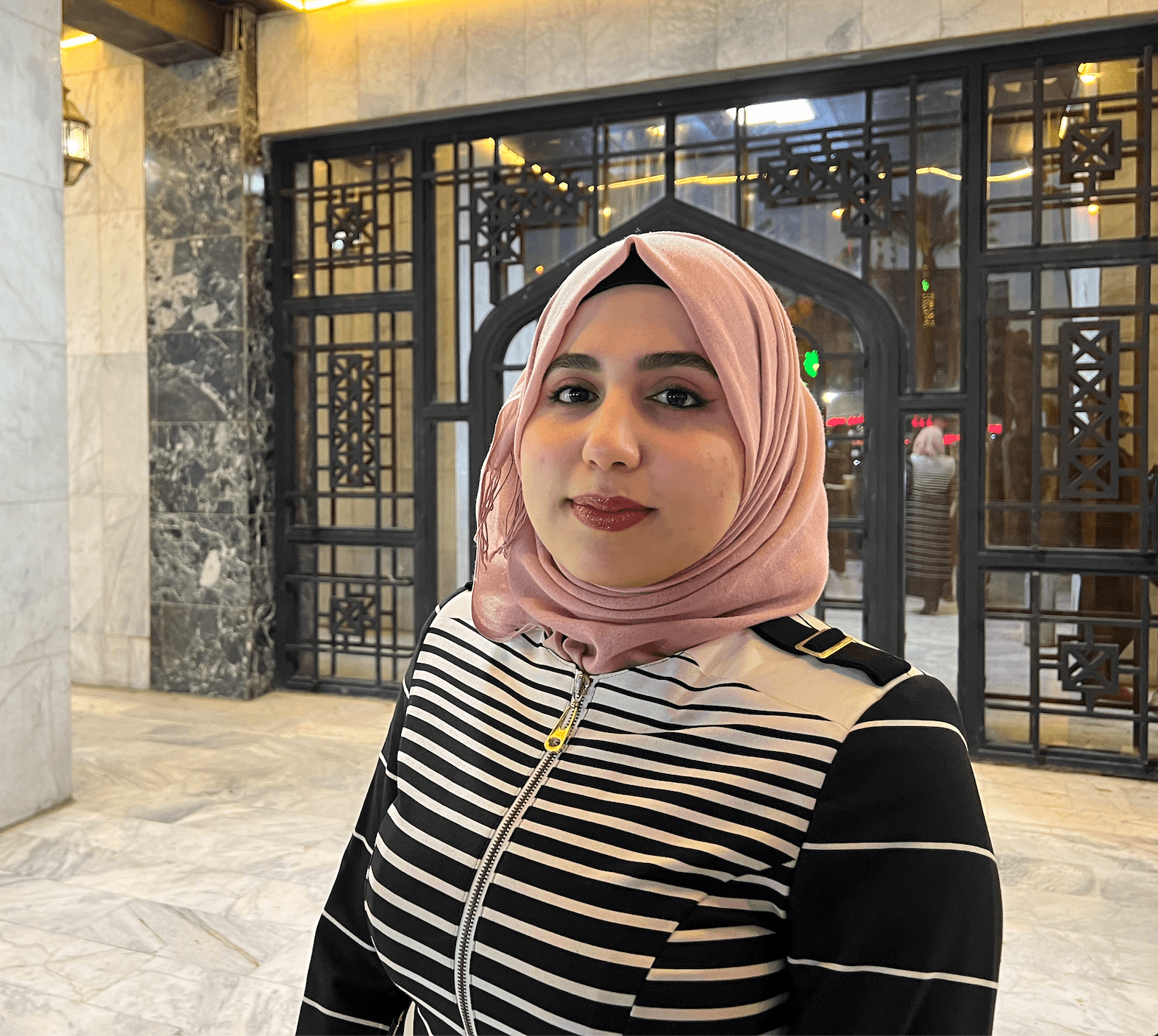

Malek grew up in Baghdad during a turbulent time. After the fall of President Saddam Hussein in 2003, different ethnic and religious groups, mainly Shias and Sunnis, fought for power in Iraq. Car bombs ripped through the city on a daily basis. Kidnappings were rampant.

Most Iraqis have some sort of experience with suicide attacks and car bombs, Malek explained.

That includes herself.

When she was younger, a car bomb exploded at the entrance of her school, killing many people. Malek said she can still hear the sound of the explosion in her head to this day.

“I was just a child,” she said, “in primary school. I thought that I was going to die. I just wanted to see my parents. I left my books everywhere. It was a hard thing for a child to consume.”

The constant preoccupation with survival made it almost impossible to focus on anything else, she explained. Her father didn’t allow her to leave home on her own. He insisted that the whole family stick together, so that if there was an attack, they would all die together.

A fragile stability

During those years, many Iraqi musicians fled the country. When ISIS rose to power and occupied much of Iraq, it banned all music.

But Iraq feels much safer these days, Malek said, even though stability seems fragile. That’s why she and her family try to savor every moment of the concert.

On the other side of town, at a small studio, a group of young Iraqis got ready to practice the oud. It’s a pear-shaped, stringed instrument similar to a lute. And it’s central to Middle Eastern music.

But just as the group was ready to start, suddenly the power cut out — a daily occurrence in Baghdad.

Being used to power cuts, the students quickly placed their cell phones in each corner of the room, and the little bright screens lit up the room.

Thirty-two-year-old Mostafa Rashied is one of the 50 oud players in “The Peace Orchestra For The Iraqi Oud“, which has been holding concerts all over Iraq in the past year.

Rashied learned English while working for different American companies and NGOs, and he said in his time working with Americans, he has been surprised by the image some of them have of Iraq.

“Guys, we’re not living [in] the desert,” he said, “we’re not riding camels, we’re riding cars. We have museums. We have theaters. We have the river here.”

In 2013 Rashied thought about leaving Iraq, like his two brothers did, who now live in Finland.

“I was trying to apply for one of the immigration programs, but then I thought about my family. I can’t leave them. And I love this country. I want to be part of the success of this country,” he explained.

These days, Rashied is more hopeful about the future. Iraq may still have many problems, like its ever-dysfunctional politics, he said, but overall, he’s optimistic.

“I think it’s more secure right now,” he added, “there [are] no bombs, we can live with this.”

As a result, after decades of conflict and insecurity, concert halls are filling up and music lessons are happening without interruption.

And Iraqis like Mostafa Rashied and Zahraa Malek are hoping that the relative calm continues.

So now, instead of car bombs and gunfire, the sounds of classical music and the oud can be heard throughout the city.

Related: Iraqi author Ghaith Abdul-Ahad on the ‘unbuilding’ of Baghdad