The village of Kijumba sits surrounded by tall banana trees and cassava plants just off the newly constructed roads of the oil-rich Hoima district in Uganda.

This is where 49-year-old Hope Alinatiwe has spent her entire life, cultivating the land to feed herself and her eight children.

Like many rural Ugandans, she is cash-poor but land-rich – meaning her small plots of land are her only assets.

But recently that land has come up for grabs because of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), an ambitious project that will run more than 800 miles from western Uganda to neighboring Tanzania.

In 2018, Alinatiwe said she was told she would need to sell some of her land to make room for the construction of the new pipeline.

“I was told to sign the contract and to stop using the land,” she said.

So, she did. For the next four years, Alinatiwe waited for compensation, and in the meantime, her land went to waste.

By the time she was paid this past September, she had lost out on four years of farm earnings for what she said was meager compensation.

“The money we were given was too little,” for the land, based on its current value, Alinatiwe said.

Now, having lost her primary source of earning, she can no longer afford to send her kids to school and struggles to find work to feed her family.

Alinatiwe’s experience highlights what has become a flashpoint in these early days of development for Uganda’s ambitious oil development: land.

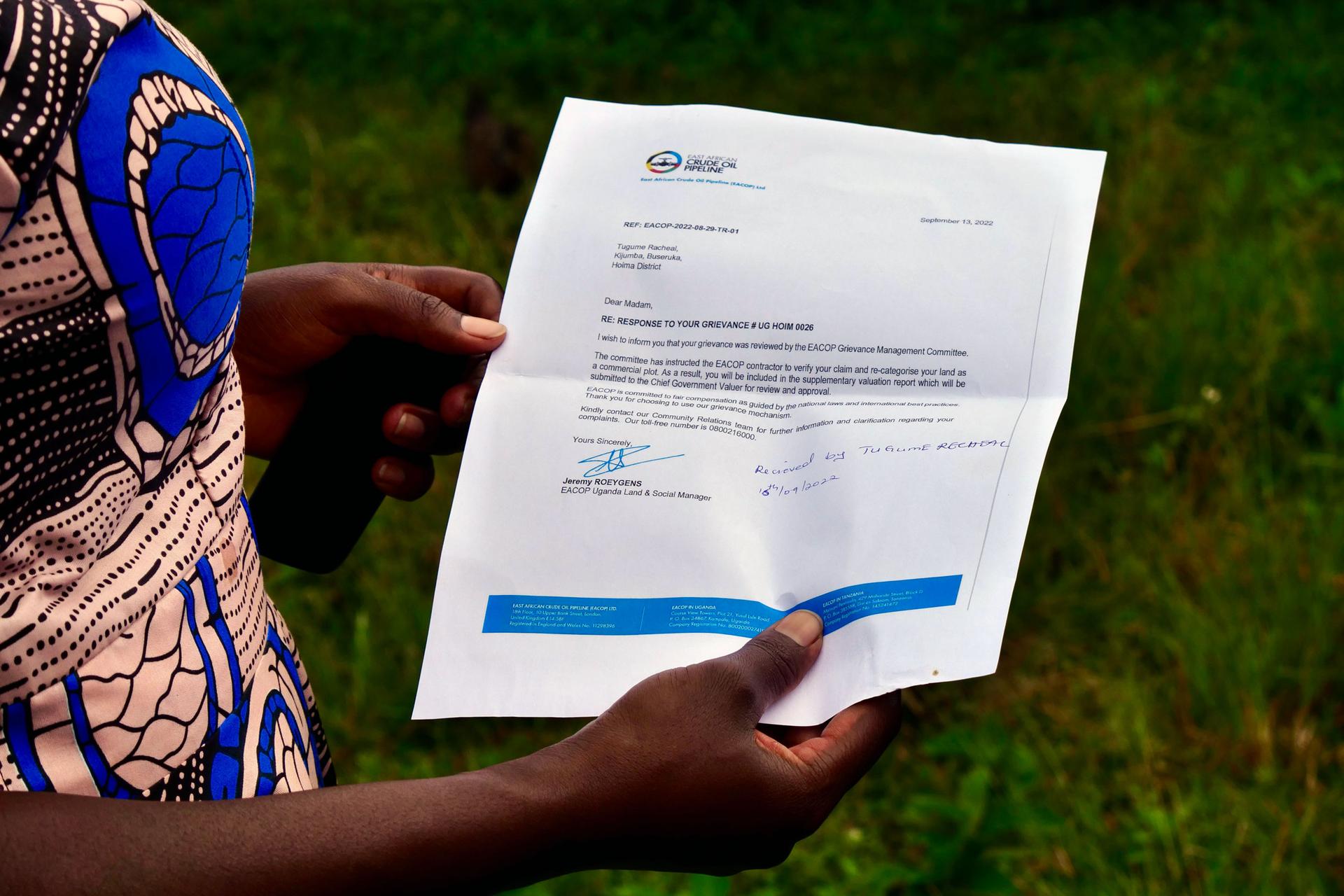

Rachel Tugume, also from Kijumba, has a similar story.

“They told me, ‘Rachel, the pipeline will go through your land.’ So, I waited for them to come, and in 2019, they came and stopped me from using my land,” she said.

“If you have cassava in our place, you are a good farmer and you are a rich person,” Tugume said.

She was offered about $130 for her land — the amount determined by her land size at the time. She said she can make twice that amount per year by farming. And as time passes, the land has become increasingly valuable due to the nearby oil and infrastructure development.

“The price only keeps going up every year,” she said.

Up to now, Tugume has held out on selling, instead trying to negotiate with the EACOP company for a better deal for her land.

In the meantime, her demarcated land has become full of weeds as Tugume continues to abide by the terms of sale, which include ceasing to grow crops that take time to harvest. She estimates she has lost millions of Ugandan shillings in profits by not cultivating the land for years.

She said her issue isn’t with the oil pipeline itself, but with the impact it has on locals like her.

“We are near the oil and gas, we are near the airport, and we are the people who are affected,” Tugume said, estimating she has lost out on millions of Ugandan shillings of earnings by not using her land that has been earmarked for construction.

“At least they can help us,” she said. “So, we can also benefit from the oil and gas.”

Displaced by oil

In other parts of Hoima, construction for the oil project has already begun.

In Buliisa, on the shores of Lake Albert, a central oil processing facility is in the works.

That’s where John has lived all of his life, until he was told to sell his land to make room for oil construction. He asked to only use his first name, fearing harassment.

“I requested for land compensation,” he said, rather than getting meager monetary compensation.

When that didn’t work out, he said he refused to sell the land.

“We were taken to court,” he said, and lost.

John said he was later forced to leave his land, which he relied on as a source of income.

“My children are not in school. I cannot have money to earn my living,” he said.

Since then, he has relocated to his relative’s property, which is adjacent to another construction site.

“There is a lot of noise, a lot of sand, dust, a lot of floods of water,” John said.

Uganda’s government has said that they are compensating people fairly. “There is no area in the country that has been assessed for oil and gas development before full and adequate compensation of the project affected persons,” said Gloria Sebikari of the Petroleum Authority of Uganda, who acknowledged there were some delays in payment due to COVID-19.

But for activists, the ongoing disputes over land compensation in the areas closest to the oil development project is proof that the oil project will not benefit ordinary Ugandans.

“There is no way you can expect these huge projects to benefit the poor people, the average people,” said Dickens Kamugisha of the Africa Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO).

“The money will be earned and only the rich and the powerful will be the ones to take that money,” he said.

This month, AFIEGO and other organizations sued Uganda and Tanzania over the oil pipeline project at the East African Court of Justice, arguing that the project violates international law and regional environmental treaties.

Threats to vital wildlife

In nearby Bugoma forest, conservationist Nazario Asiimwe walks through the dense bush, pointing out the diverse biodiversity.

Environmental activists are concerned that the pipeline project could potentially impact forests like this one, which is home to protected species like the chimpanzees.

Asiimwe, who works on forest conservation, worries the species could be harmed by the construction.

“Because chimpanzees, they move everywhere. They can move to where they want to construct the pipelines,” Asiimwe said.

Both the Ugandan government and the oil companies involved have responded to critics by saying they have taken measures to mitigate any potential negative social and environmental impact of this development project.

But AFIEGO’s Dickens Kamugisha said that is not enough, and that fossil fuels are not the answer for Uganda.

“I don’t think we should be saying let’s also destroy this nature for us to make money,” he said.

“We can harness our nature and ensure that we get money but we also sustain our environment.”

Related: Why African countries like Uganda are investing in fossil fuels, Part I