This analysis was featured in Critical State, a weekly foreign policy newsletter from Inkstick Media. Subscribe here.

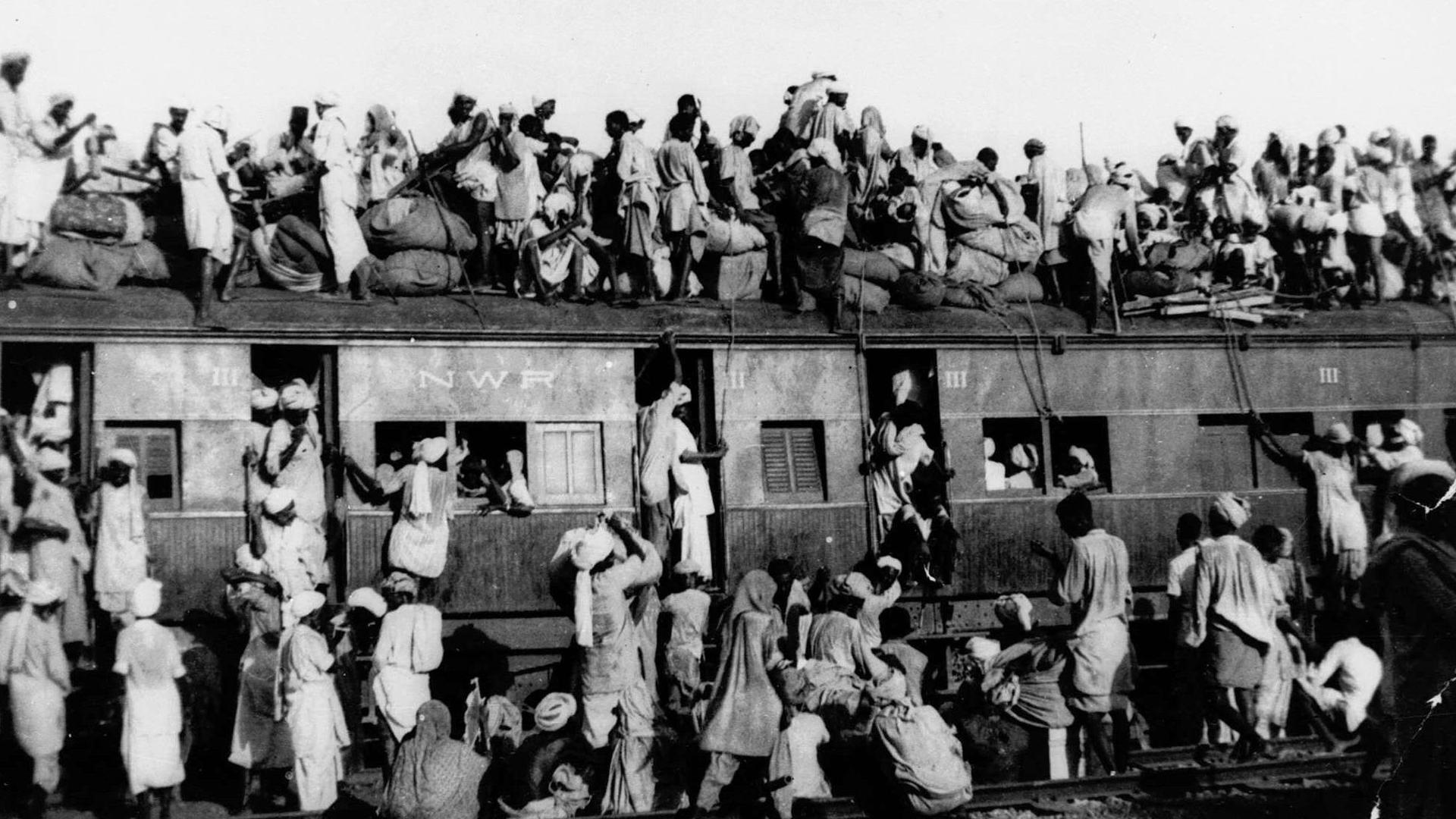

If states told ghost stories, they would tell them of past partitions. Acts of partition, which span time and geography, unmake and remake states and people, often at the behest of at least one more-powerful third party. While lives may continue in partitioned states, it is not the sort of action undertaken willingly by the polity without other tension driving it to be a less-bad option. States are not living entities sharing campfire stories but instead are made up of people with historical memory. And the stories of partition are powerful in shaping how a state may react to future divisions or the possibility of reunification.

In “Connected Memories: The International Politics of Partition, from Poland to India,” Kerry Goettlich talks about partition as a memory held collectively and one where past examples in faraway lands are used as a tool for understanding and arguing about the present.

“The idea of ‘memory communities,’ likewise, does not break with the idea of a community of some kind,” Goettlich writes.

“While Western and Eastern Europeans’ memories of the Holocaust, the Second World War, and their outcomes may clash, they do so as a contest over the meaning of a series of tightly connected historical events, and ultimately as a struggle over what it means to belong to the collectivity called ‘Europe.’”

The way that people in countries in Eastern and Western Europe collectively respond to the experience of World War II shows shared events as contested memory and about memory in relation to other communities. What makes memories of partition so distinct is that they look for similarity and precedence in distant events, but events of a similar kind.

“The picture of partition that emerges from Poland to India here, however, is not one in which partitions are discrete, disconnected events, as assumed by much literature on partition, nor are memories of partition only relevant to those who experienced them,” Goettlich writes.

“Instead, the argument here is that social memories of partition traveled, and shaped how partition was seen, one way or another, beyond their original context.”

To explore this concept, Goettlich takes the partition of Poland, when from 1772 to 1795, Prussia, Austria, and Russia divided and occupied the land that had once been a distinct nation. This historical understanding of this event in the United Kingdom, while not leading to any change for Poland itself, shaped how British foreign policy approached a range of foreign policy decisions, including proposed partitions in Belgium, or how the gradual dissolution of the Ottoman Empire was to be handled.

“Only through the partition of Ireland, for example, particularly through the work of the imperial federalists,” Goettlich writes, “did it become possible for some to articulate ‘partition’ as a solution to intercommunal conflict, and to forget its negative associations with Poland.”

The story of Irish partition, in turn, echoed through the wider world. Goettlich opens the article with Ireland’s President Michael O’Higgins tying the partition of Ireland to the colonial struggles across the globe. If partition is a ghost story told by states, reunification after is a campfire song sung afterward.

Related: State reformation: Part I

Critical State is your weekly fix of foreign policy analysis from the staff at Inkstick Media. Subscribe here.