On March 24, exactly one month after Russia invaded Ukraine, North Korea put itself back on the world’s center stage by announcing that it had successfully launched a long-range ballistic missile called the Hwasong-17, capable of carrying multiple nuclear warheads all the way to the continental US.

The weapon is considered such a game-changer that people in the nonproliferation community even have a nickname for it: the Monster Missile.

What makes the Hwasong-17 different isn’t its range — it is its payload. North Korea has had a missile that can reach the US for some time now, but it can only carry one warhead.

“What they really want to do is put multiple warheads in a missile,” said Jeffrey Lewis, an arms control policy expert and the East Asian director of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey which tracks these sorts of things. “They need that to overwhelm our missile defenses.”

Just days after the March launch, North Korea released a video lauding the achievement. It is unintentionally hilarious, opening with Kim Jong-un — the Great Leader — in a “Top Gun”-like leather jacket, checking his watch as if he were late for a train. He’s flanked by two generals in uniform, and the trio are being trailed by an enormous mobile launch vehicle, rocket included.

The actual launch didn’t take place until around minute four. That’s when we saw ignition, smoke and then liftoff before the camera cut to a still photograph of Kim and a bunch of his generals excitedly punching the air. The only trouble was, it may not have happened that way. According to Lewis, it may have been an elaborate ruse.

“We think they tested two missiles in March, one that worked and one that didn’t,” he told the Click Here podcast, revealing his team’s analysis for the first time. “The simplest answer is that they launched the big one on March 16th. But it blew up. So, they came back a few days later, launched a different missile,” and put it all together to imply that the Hwasong-17 test had been a success.

Looking through a soda straw

Back in the 1990s, when Lewis was starting out in the nonproliferation business, satellite imagery was expensive and mostly controlled by governments. But over the past decade, the quantity of satellite imagery has increased exponentially. Private imaging satellites from firms such as Maxar, Capella Space and Planet Labs have provided researchers and analysts with access to hundreds of thousands of images they rarely saw before.

The result is that they can now keep track of everything from crop yields to troop movements, and they have all kinds of satellite images to choose from — high-resolution ones that can make out cars, and even individuals, to lower-resolution shots that indicate a building, but turn a moving car into a mere smudge. Companies like Planet try to take a picture of the whole world every day at about 3 meters (10 feet) in resolution.

Lewis said, to be able to track events in places like North Korea, his team studies moderate-resolution images to spot change, which then allows them to use high-resolution pictures to zero in on what might be unfolding on the ground.

“High-resolution images only give you a picture of a very small area,” Lewis added. “It is like looking at the Earth through a drinking straw.”

And if you know exactly what you’re looking for, it is invaluable.

Back in 2018, Pyongyang released photos of Kim touring a factory where proliferation experts believed the regime was making crucial parts for short-range ballistic missiles. One of the propaganda photos North Korea released was of Kim looking at a map, which, on closer inspection, suggested the plant was about to undergo a huge expansion.

“They had not started the expansion yet. So, it was just this tiny, tiny, tiny little facility,” Lewis said.

So, his team tasked a high-resolution satellite, with that soda straw view, to take a closer look, and that allowed them to watch as North Korea knocked down buildings and built new ones.

The construction became one of the first real indications that North Korea was stepping up its short- and medium-range ballistic missile program. “And we really got that all from just Kim standing in front of a map,” Lewis said. “And then Planet’s 3-meter imagery, tipping us off as to when the construction of that facility had started.”

He’s all ears

North Korea has tested two kinds of ballistic missiles: a short-range one it says it would use against American forces, should they ever invade from South Korea or Japan; and a long-range one — like the Hwasong-17 — featured in that March propaganda film, which has been an obsession of Lewis and his team since the spring.

“Sometimes, people say, ‘Why would you look at propaganda? It’s just lies,’” Lewis said. “The answer is, when you catch someone in a lie, then you’ve learned something very interesting about what they care about, what they want you to think and what they want you not to know.”

Case in point, Kim’s preoccupation with a particular part of his anatomy.

“My favorite thing that North Korea loves to lie about — which they’ve stopped doing, so I’m a little disappointed — is to adjust the size of Kim Jong-un’s ears,” Lewis said.

Apparently, the Great Leader thinks his ears are too big, or at least he did.

“We would just see image after image after image when they had made his ears a little bit smaller,” Lewis said. “He clearly cares about his ears. His ears look totally normal to me, I don’t see what the problem is.”

Which brings us back to the March video. Not long after it was released, a senior correspondent at NK News named Colin Zwirko suggested that something was off.

“He was the first person who said, ‘I don’t think this is right,’” Lewis said. “And that’s music to our ears, because that is like waving a red flag at a bull … And my whole team was like, ‘Well, let’s check that out.’”

Microanalysis as a superpower

Lewis has an office at the Middlebury Institute in Monterey, but can rarely be found there. He tends to sit in the graduate research assistant room because, he said, it is more fun.

“I have a very nice office. It has lots of books in it,” he said. “The one thing it does not have is the other human beings that I need to be successful and feel fulfilled at work.”

The people he likes to sit with are a kind of super-smart Team America: Lisa Levina speaks Korean and models rockets; Steven De La Fuente is great with satellite images and heat maps; John Ford has an uncanny ability to remember everything he sees; Tricia White, among other things, finds clues in social media; Michael Duitsman is an expert on shadows; and Ben Mueller comes from a STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] background, so they call him the “Walking Computer” because he seems to be able to answer just about any question they put to him.

The superpower they share? Microanalysis — the ability to spot the tiniest of incremental changes and give them meaning.

When Duitsman began to dig into the March video this past spring, he started with something easy to measure: the angle of the sun. The March 24 launch was billed as having taken place in the afternoon, but Duitsman said video seemed to have been filmed in the morning.

“There are tools online that you can use to measure the angle of the sun at a particular time of day and determine which direction the shadow should fall,” he said. “We could compare the direction the shadow would fall at the two different launch times and determine how that compared with what was seen in the video.”

They had their first thread, and they started to pull.

Burn scars don’t lie

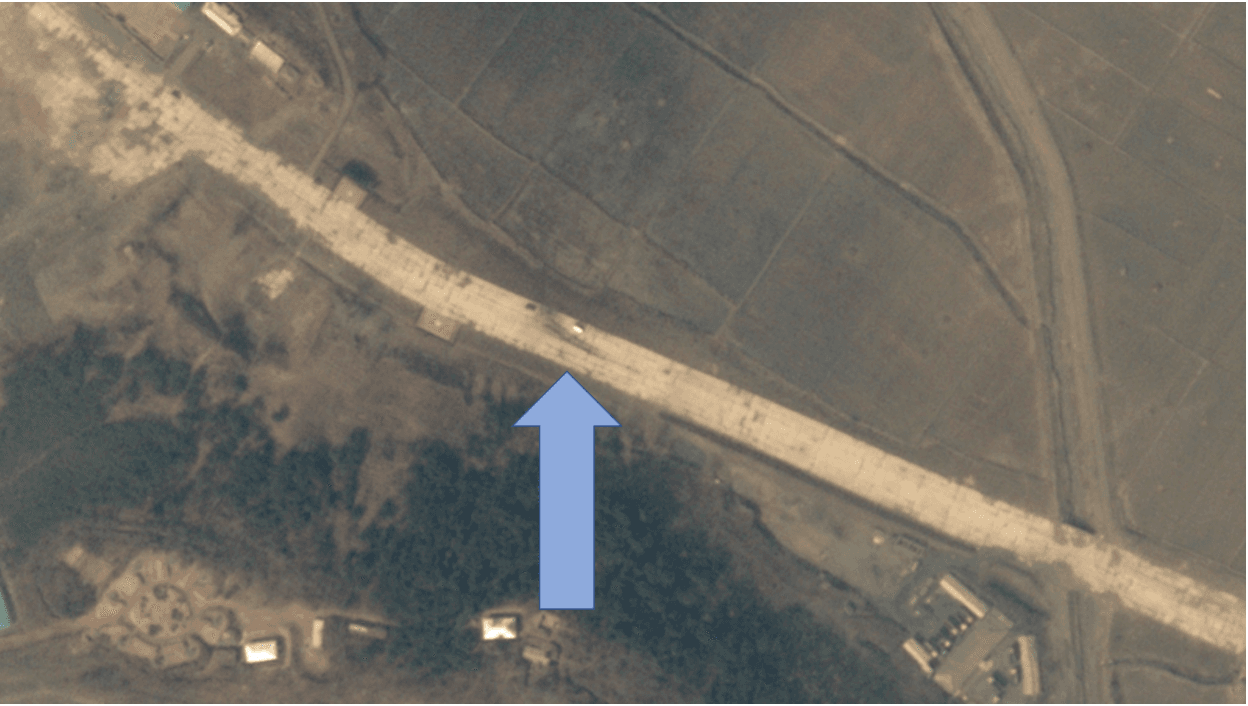

Months later, Lewis sat down with the Click Here team to explain the team’s investigative process. He began with an image from the North Korean video. He pointed out what looks like that mobile launch truck that was dogging Kim’s heels in the opening scenes of the video. It is sitting on a tarmac at a funny angle and if you look really closely, you can see a white spot that looks like that missile standing up on its end.

“And what’s notable about this is there’s enough detail in this drone image that you can tell exactly where on the road this truck is,” Lewis said.

Then, he pulled up a second image from Planet Labs — a high-resolution satellite picture from March 16, almost 10 days before the Hwasong-17 launch was supposed to have happened. And it’s exactly the same spot.

“You can see all the same buildings,” Lewis said. “You can see the same fields. The road looks the same, even the damage to the road is identical. And you can really see that detail and the truck is gone, but there’s a black kind of smear. And that smear is the burn scar.”

It’s the kind of burn scar that’s left after a fiery missile launch, and the half rectangle pattern appears to trace the outline of a launch truck, like the one in the video. The only problem? This photo was taken eight days before the North Koreans claimed to have launched the Hwasong-17.

“It’s almost like you went and looked at Kim Jong-un and, and you asked him like, ‘Hey, did you eat those brownies?’ And he says, “No, I don’t know who did it,” but he’s got chocolate smeared all over his face,” said Lewis. “I mean, it’s just such a perfect giveaway.”

When Lewis and his team went back over the satellite images from March 24, the day the North Koreas claimed they successfully launched the Monster Missile, the burn marks were nowhere to be seen. In fact, there’s no evidence that a missile was launched that day at all.

Mystery Solved

Lewis readily admitted that the process by which his team pieces together something like this is a really chaotic, iterative process of pulling in all kinds of data, comparing, organizing and then bouncing explanations off your colleagues.

“What happens is you start to realize what the answer is,” he said. You know, there’s almost a kind of gravity that the truth has where it’s clear that one answer is simpler than the others, one answer explains all the evidence pretty well.”

And the simple answer in this case: North Korea launched two missiles in March. One that worked and one that didn’t. Lewis and the team believe they launched the Monster Missile on March 16. They filmed it. Kim was there. It was on that launch vehicle in the movie, but it blew up, so they couldn’t announce it.

“So, they came back,” Lewis said, “and they launched a different missile that they were pretty sure would work.”

John Lauder used to serve as director of the CIA’s nonproliferation center and he said that the secret sauce in looking at satellite imagery like this are the signatures that Lewis and his team put together.

“It’s one thing to say, ‘OK, great. Here’s a picture or a video of a missile launch,’ but it’s all the little things to go with it,” he said, “like burn marks and the trailers in the background and the vehicles that are in the back that help, over time, to give us a real sense about what’s going on.”

Lauder said he is a “believer in those capabilities and what folks like Jeffrey Lewis are doing,” but the downside to all this transparency is that it permits adversaries to understand just how much they are revealing by releasing things like that March video. “Maybe the North Koreans will be a little smarter next time when they put together a video that might give something away.”

And there will be a next time. Kim may have given up on photoshopping his ears, but he’s unlikely to shake his obsession with his Monster Missile. And both Lauder and Lewis said that eventually, he’ll get the Hwasong-17 to succeed.

“And one of the things I’m concerned about,” Lewis said, “is we’re not really emotionally ready to have that conversation.”

This story originally appeared in The Record.Media. It was written by Dina Temple-Raston and Will Jarvis, with additional reporting by Sean Powers.

Related: Japan gears up for evacuation drills amid spate of North Korean missile tests