Sylvia Fifer always loved to dance.

Now 85, she met her husband at a dance in London one Saturday night in 1955. For more than six decades, they would go dancing a few times a week.

“I didn’t say we were good,” Fifer joked. “But we enjoyed what we did.”

Their last dance together was in April 2020, when her husband contracted COVID-19 and died within a week of the diagnosis.

The grief was almost more than Fifer could bear.

“I was very, very lonely,” she said.

When Fifer sought help from her general practitioner, she was given more than just a pill. She wrote Fifer a social prescription — to a dance club.

Social prescriptions are relatively common in the United Kingdom, especially to treat loneliness and isolation. When these conditions were exacerbated by the pandemic, the UK already had a strategy in place to help those who need it most.

Medicine works for kidney ailments, diabetes and heart disease, but loneliness isn’t an organ or a disease that a pill can target, according to Dr. Ashwin Kotwal, a geriatrician and assistant professor at the University of California San Francisco’s School of Medicine.

“As people get older, their lives become increasingly medicalized. Very few clinicians are actually thinking about people as a whole person.”

“As people get older, their lives become increasingly medicalized,” he said. “Very few clinicians are actually thinking about people as a whole person.”

It requires a different approach.

Doctors now know that social isolation is linked to an increased risk of health problems like dementia, heart disease and stroke. Loneliness also increases the risk of high blood pressure. And people with fewer connections are also at greater risk of premature death.

In 2017, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called loneliness an epidemic. But in the five years since Murthy highlighted the issue, the US has devised no strategic approach to mitigate loneliness.

Related: The ‘forgotten victims’ of femicide in France: Women over 65

In the UK, however, doctors can deliver social prescriptions through link workers — a unique role that the National Health Service began to fund in 2019.

Every general practitioner has access to a link worker and there are now more than 1,000 across the country.

Fifer wasn’t necessarily looking for a social prescription when she made an appointment with her general practitioner in London.

“I just wanted company.”

“I poured my heart out to her,” she said. “I just wanted company.”

Her doctor chose to treat her depression and loneliness by increasing Fifer’s antidepressants and also issuing a prescription for social dance.

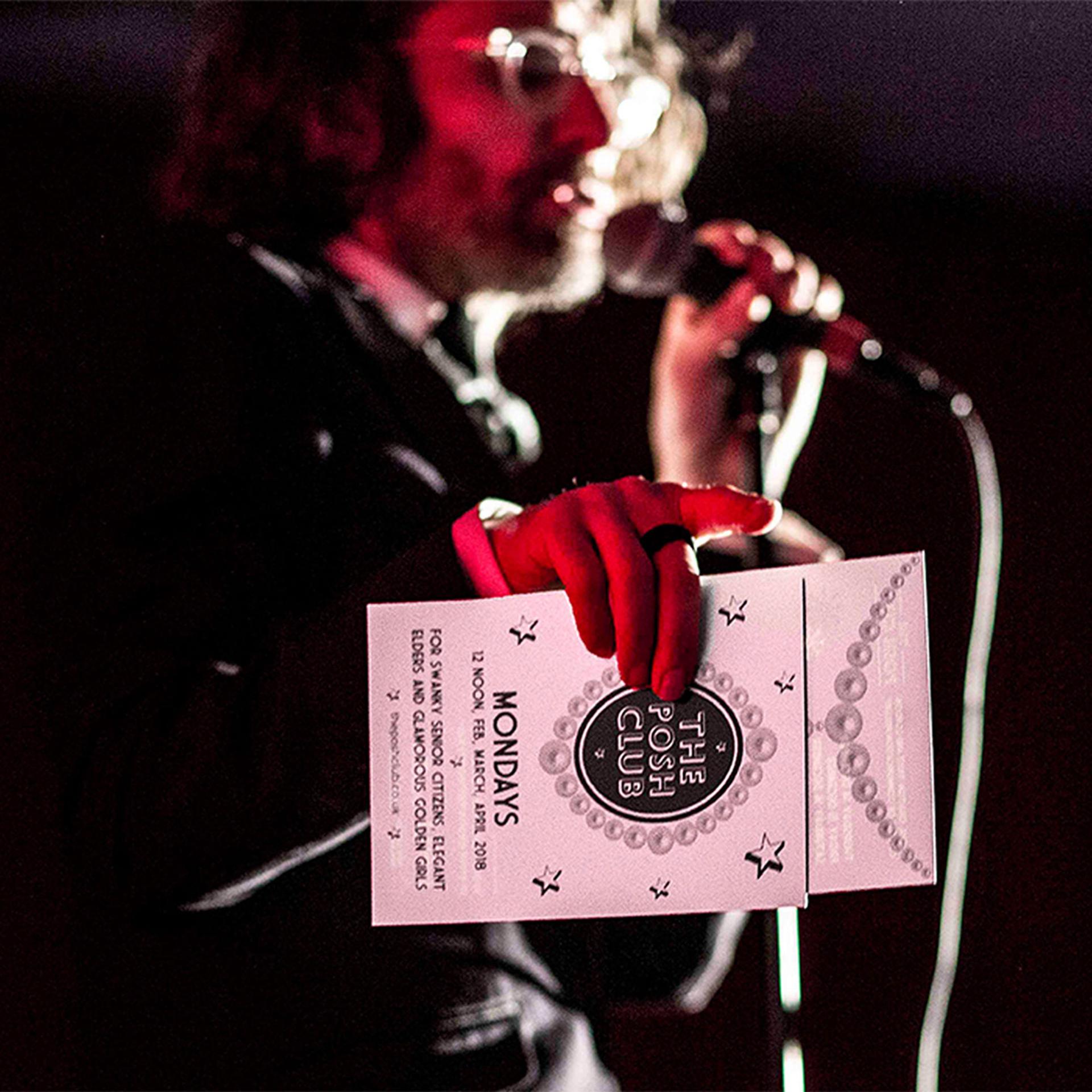

Fifer’s link worker chatted with her several times before giving her a referral to try out The Posh Club.

‘Hello, Posh Club!’

On a Wednesday morning in March, a long line formed outside St. Paul’s Church in London’s borough of Hackney, as people waited to enter The Posh Club.

“I’ve got on my posh scarf and my 100-year-old posh jacket,” said Anita, 78.

The Posh Club is a unique place that offers a weekly afternoon tea party and cabaret for older people.

The “posh” name is tongue-in-cheek. Entry to the club is less than $10. There is, however, one rule: “If you ain’t over 60, you ain’t getting in,” Azara Meghie, the host, quipped.

Under a disco ball inside a church-turned-club, many people gathered, accessorized with high heels, silk ties, shimmery shawls and tassel earrings, with Donna Summer’s “Hot Stuff” blaring through speakers.

“I never envisioned that I would feel so strongly about meeting people,” said Fifer, who has been attending weekly for almost a year.

The Posh Club was started by a queer nightlife collective called Duckie in 2013, after one of the group’s leaders noticed that his own 80-year-old mother was living in near isolation.

The entrance fee comes with unlimited servings of tea and coffee, plus sandwiches, cakes and entertainment. The acts include dancers, musicians, drag performers and comedians.

It also challenges stereotypes of what an older person enjoys, Meghie said.

“They’re still being treated like there’s life there.”

A squad of volunteers, much younger than the guests, brings the club to life each week.

Ministries of loneliness

In 2018, then-British Prime Minister Theresa May appointed a minister for loneliness and announced a national strategy to combat loneliness and social isolation.

Later, the role was absorbed into the department for digital, culture, media and sport.

Last year, Japan also added a minister of loneliness and Australia has proposed a national strategy.

Meanwhile, the US has no prescription for dealing with isolation and loneliness for its 54 million seniors.

American doctors tend to think it’s not their job to treat loneliness, said Dr. Carla Perissinotto, a UCSF geriatrician and professor.

“The medical model for a long time has really separated social health — health outside of the physical being — from health.”

US Surgeon General Murthy, who did not respond to requests for an interview, — has made combating loneliness his mission, calling it a “public health threat” and a “growing health epidemic.”

Related: How poetry has helped a hospital chaplain in the pandemic

He advocates for greater attention to loneliness as a health issue in America in his book, “Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World.”

Social prescribing doesn’t fit neatly into the US health care system, a fee-for-service setup in which providers earn money based on the number of services. The more times a person goes to the doctor, the more money health care providers make.

The system incentivizes the wrong behavior, said Abner Mason, founder and CEO of California-based SameSky Health, which helps older people of color access Medicaid and Medicare Advantage.

“If you make more money the sicker people are, it’s just not a good health care system.”

“If you make more money the sicker people are, it’s just not a good health care system,” he said.

The Affordable Care Act set out to change the system to one in which providers are reimbursed based on the quality of care. Financial incentives encourage providers to create programs that reduce poor health outcomes — including loneliness.

This could also help save money for the government.

Related: Can we improve the way we age?

A 2017 AARP study found that Medicare spends an average of $1,608 more annually for a person with limited social connections than for a socially active one — that’s an estimated $6.7 billion in added Medicare spending each year.

Not a perfect system

Social prescriptions come at a cost — not only in terms of the addition of link workers — but also for the patients.

Britain’s National Health Service doesn’t cover Sylvia Fifer’s fee to enter The Posh Club, or any other costs incurred.

“It’s based on the assumption that there are services available in the community already and that somebody is funding them,” said Dan Hopewell, a director at the Bromley by Bow Center in London.

But that assumption is erroneous. The Posh Club’s funding, for example, ran out in March. They now await funding from the National Lottery, according to the club’s website.

Fifer, who lives in a big city, may have other options. But social prescriptions are harder to fill in small towns or rural areas, where choices are limited.

Related: Feminist tango collectives take center stage in Argentina

The NHS does not provide subsidies for transportation to fill social prescriptions.

The National Academy for Social Prescribing also found racial inequities in the system, with Black, Asian and ethnically diverse people underrepresented in social prescribing.

For Fifer, it’s been a life-changer. She made a friend at The Posh Club who lives nearby, which has helped immensely with her loneliness.

“Being thrust on your own is very difficult,” Fifer said.

“But you know, when Elaine phones up and says, ‘Where are we going tomorrow?’ It’s brilliant.”

Sofie Kodner and Zachary Fletcher are writers with the Investigative Reporting Program at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. The IRP reported this story through a grant from The SCAN Foundation.