For this man in Istanbul, the pandemic renewed a lifelong passion for drawing

On a recent morning, Ahmet Faruk was out on the streets of Istanbul, looking for the subject of his next art piece.

He walked slowly, stopping to inspect the buildings around him. Here, narrow, cobblestone roads lead to the Süleymaniye Mosque, a touristy spot. But it’s the neighborhood behind the famous landmark that most interested him.

“Whenever I walk around this neighborhood, it inspires me with some details that I find in [the rubble]. And today, I think it’s not going to disappoint me,” he said.

Architectural details, geometric shapes and colors — these kinds of details speak to him. And the Süleymaniye neighborhood, with its historic buildings from the Byzantine and Ottoman empires, has plenty of character to absorb. Suleyman the Magnificent (1520–1566) — whose reign was the longest of all the Ottoman sultans — founded the quarter.

Faruk, 27, studied the history of the Ottoman Empire. Now he teaches history at the Ibn Haldun University in Istanbul. He said that he has been fascinated with architecture from a young age. When he was 7, he would leaf through encyclopedias and travel magazines, captivated by the pictures of old monuments. He would try to copy them with pen and pencil on paper.

As he got older, though, drawing faded away into the background of his life. Work and studies took priority. That is, until two years ago — when the pandemic hit. Istanbul, like so many other cities around the world, came to a standstill.

Related: In a Turkish border town, migrant ‘pushbacks’ from Greece turn deadly

“I was at home. I had more time than any time before. This was one of the few advantages of this pandemic for me,” he said.

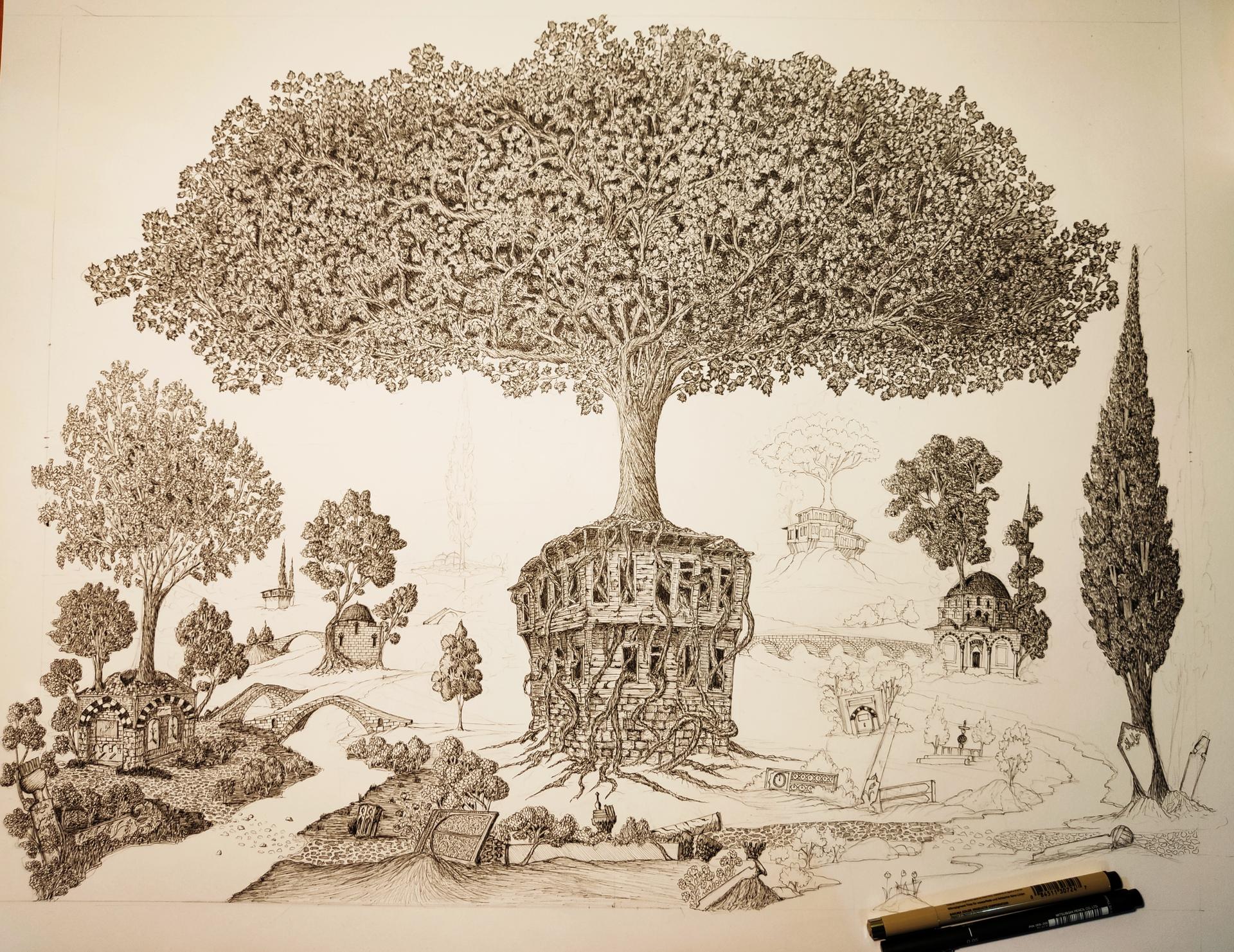

Faruk picked up his sketchbook, pens and pencils and wandered around the city, looking for forgotten, underappreciated buildings. Then, he brought them to life on the pages of his sketchbook. Lately, he has been focusing on Islamic architecture, specifically, mosque domes and minarets.

“You know, [Istanbul] is a big, cosmopolitan city, everyone is in a rush,” he explained. “It’s huge and crowded, and usually, you miss so much beautiful stuff.”

As he journeyed through the streets, he picked different things to draw. An old, rundown building here, a mosque with tall minarets over there. It was like all of the sudden, this neglected passion of his had found its way back into his life.

Most of his excursions are spontaneous. Sometimes, he draws quick sketches on the spot, or takes photos of a site and finishes it at home. Depending on how elaborate the work is, it can take him hours or days.

In the Süleymaniye neighborhood, Faruk settled on a subject for that day: A wooden, three-story house. Some of its windows were broken, but flower pots and laundry hanging out to dry were signs that this was someone’s home.

The humble structure stood out to him for its charm and personality and the fact that it was just a part of the everyday landscape — not a tourist attraction.

Related: Turkey’s ‘whirling dervishes’ strive to keep the practice sacred amid tourist demand

Faruk sat on some steps opposite the house and started to draw. With a few short, quick flicks of the hand, an outline emerged on paper. Every now and then, he paused, looked up and then continued with his black pen.

Faruk has made dozens of drawings like this in the last two years. He also works in color and sometimes, adds in paint. His drawings reflect the busy, populous feel of Istanbul, with buildings practically on top of each other, sometimes appearing to almost spill out of the picture plane.

Some of his work is detailed, elaborate and exacting while others have a more gestural, impressionistic style.

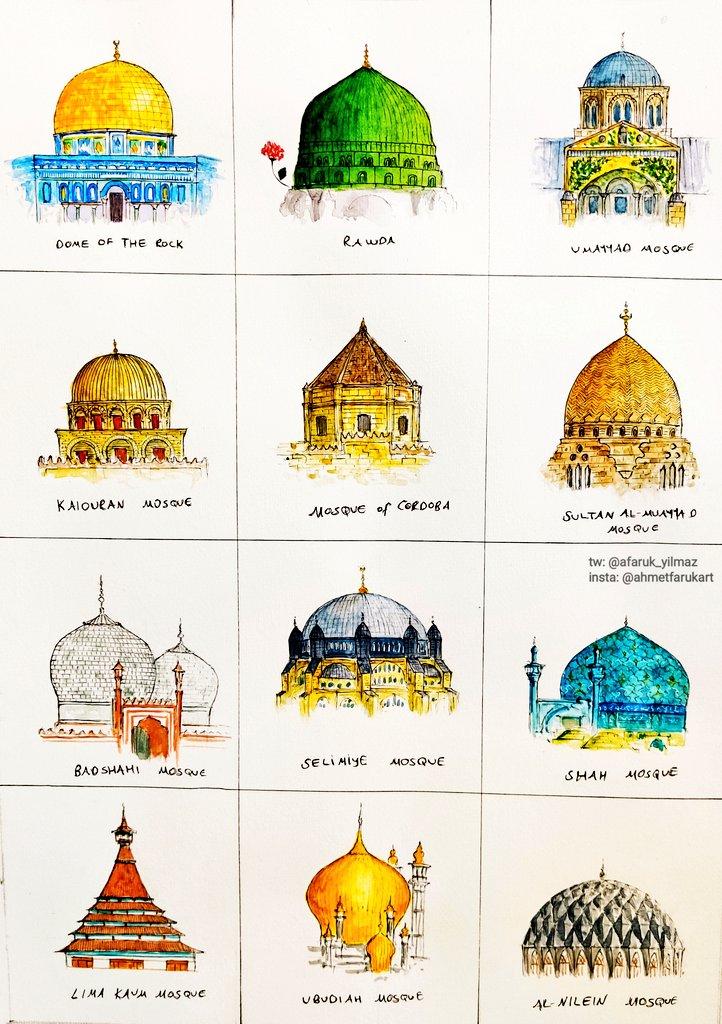

One of his pieces went viral on social media. It showed nine different styles of minarets, each from a different period in Islamic history.

“It reached millions of people,” Faruk said. “It was really unexpected for me.”

Some people criticized him for not including minarets from other parts of the Muslim world.

So, he started to research.

“It’s maybe like a hundred times more diverse than I knew,” he said. “I mean, just discovering very unique styles in a small village in Malaysia or in Java, in Sumatra, in Bengal or in West Africa. I was like OK, I’m not just drawing. I’m learning by drawing.”

Related: Massive sinkholes appear in farmers’ fields in central Turkey due to climate change and drought

Faruk updated his minaret series and started another one focusing on the different styles of domes on mosques. He added color to the domes, using watercolors.

Since then, he has been getting commissions from all over the world, including from a Turkish couple in Vienna.

“They ordered four paintings with [an] Istanbul theme, with [a] Turkish cultural theme. Apparently, the reason was that their child came back from school one day with Santa Claus [stories], and they were like, ‘Oh, what’s happening? We need to teach our child about our culture and heritage. So, let’s decorate our home with Ahmed Faruk’s art,’” Faruk said with a chuckle.

Drawing is now a big part of Faruk’s life. He’ll continue teaching, but he can now afford to spend more time on drawing because he is selling his work.

But this is more than just a business for him.

Related: Move over, telenovelas. The latest binge-watching craze? Turkish dizis.

Istanbul is changing fast, he added. Not a day goes by without new demolition projects somewhere in town. A few buildings that he’s drawn — mainly residential ones — no longer exist. They were replaced by modern high-rises.

“Sometimes, it feels like a desperate attempt to save or protect, just like protecting something or someone you love,” he said. “But you can’t protect it. It’s going away. I am at least saving them visually.”

For Faruk, the pandemic gave him a chance to slow down, to pay attention to his surroundings and to document the city’s transformation.

He said that drawing has also helped him cope with stress.

“When I just take my sketchbook and start drawing, I forget about the rest,” he said. “And it’s opening a new fictional world in my mind that helps me to calm down, relax.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!