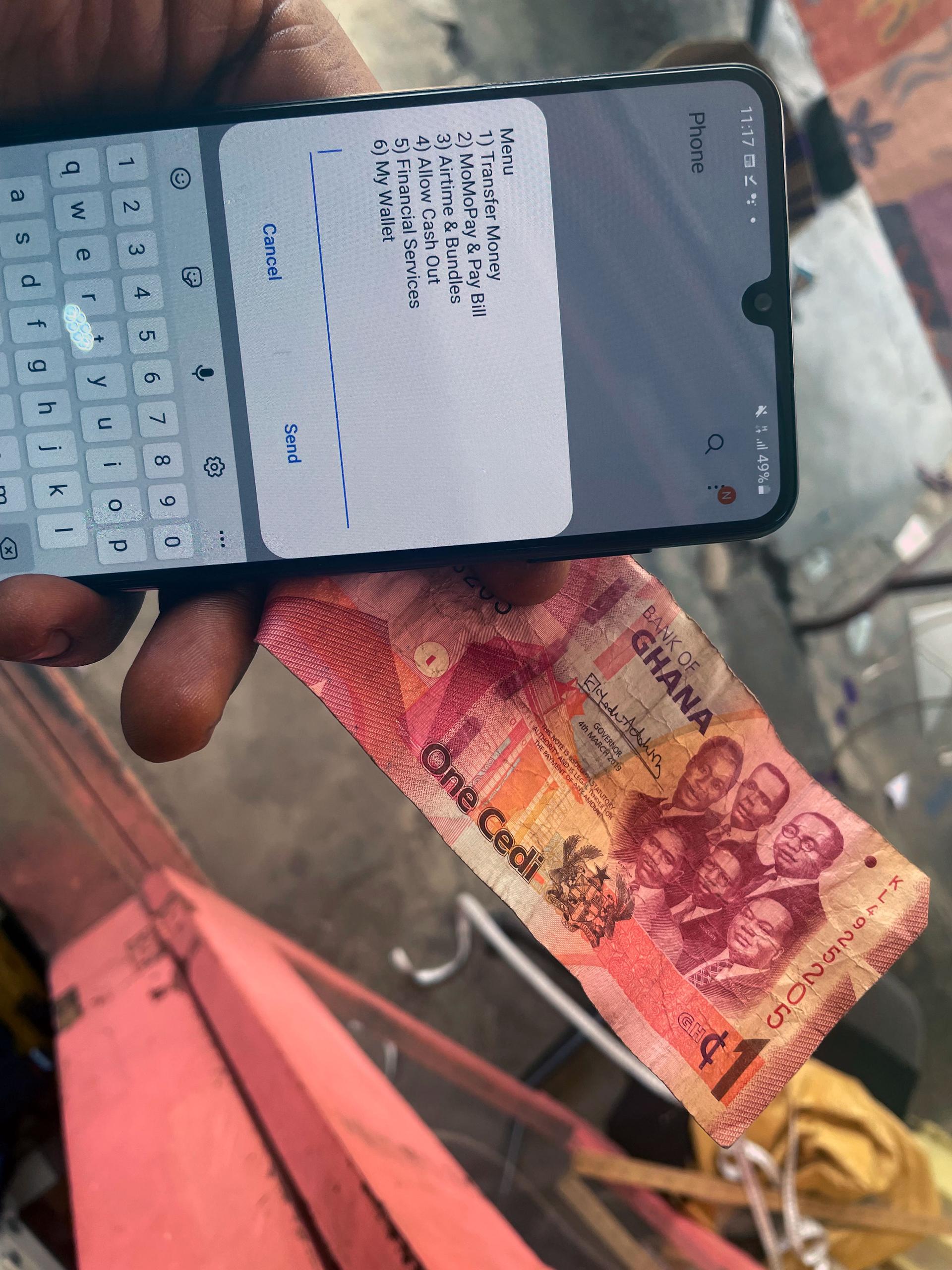

At a small, yellow telecommunications shop in suburban Accra, Ghana, Salormey Ayertey attends to her customers. They come to deposit or withdraw cash from their mobile money accounts, which are run by an array of network providers.

Ayertey has been a mobile money vendor for 11 years, and it’s her only source of livelihood. Ghana’s proposed government “e-tax” could threaten telecommunications businesses like hers. And many worry that the cost-prohibitive measure would impact the millions who depend on mobile money transfers on a daily basis.

“We are not happy about [the e-tax] at all. This is how we are also able to put food on the table. The business will collapse and it will affect us.”

“We are not happy about it at all. This is how we are also able to put food on the table. The business will collapse and it will affect us, she said.

Related: Tuvalu cashes in on its coveted internet domain name amid rise in online streaming

Ghana has one of the fastest-growing mobile money markets in Africa, with about 19 million active mobile money accounts driving the digital financial services industry, according to its central bank.

But Ghana’s debt has nearly doubled in 10 years. At the end of November 2021, it hit about 78% of its gross domestic product, up from about 40% a decade ago, according to Ghana’s Ministry of Finance.

As part of its austerity measures, the Ghanaian government proposed a 1.75% tax on mobile money transactions and electronic bank transfers of 100 cedis (about $16) and above.

Ayertey said that if the tax gets implemented, some of her customers are threatening to go back to the cash system.

“It will not help us because they [customers] are complaining that if they bring that [mobile tax], they will not do mobile money again,” she said.

Related: ‘We need a rescue plan’: Hunger in Lebanon surges amid economic crises

‘Getting tougher every day’

When news about the 1.75% proposed tax began to circulate, the Mobile Money Agents Association in Ghana immediately reported widespread withdrawals from the mobile money platforms.

Mavis Mensah, a Ghanaian who uses a mobile money platform, hopes the government reconsiders the proposed tax.

“Things are getting tougher and tougher every day. So we are pleading with the government if they can do something about it, it will be very nice, because it is too much.”

“Things are getting tougher and tougher every day. So, we are pleading with the government if they can do something about it, it will be very nice because it is too much,” she said.

Mobile money appeals to thousands of Ghanaians — especially those without a bank account — because it allows for the transfer of funds between cellphones without having to rely on the formal banking system.

The technology was pioneered in 2007 by Kenya’s Safaricom with its M-Pesa platform.

About 2 billion unbanked adults — mostly in developing countries — often face barriers to tasks as simple as receiving wages or sending money to family members.

Giving unbanked Ghanaians access to mobile money — especially women and people living in remote rural areas with unstable incomes — boosts economic growth.

Customer Andreas Akakpo also raised concerns about government spending.

“When you collect the tax and you don’t make good use of it, I don’t see why the tax should be collected. Go to the [countryside]. People are suffering,” he said.

Related: ‘It’s a casino operation’: As Turkish lira falls, some Turks turn to cryptocurrency

A parliament, divided

The tax, referred to as the “e-levy,” has sharply divided Ghana’s hung legislature, even leading some lawmakers to engage in physical brawls in Parliament last month during the contentious vote.

Members of the opposition National Democratic Congress have been fiercely opposed to the tax since it was first proposed in November 2021.

The NDC contends it would disproportionately affect lower-income people and those outside the formal banking system who rely on mobile money transfers.

“We remain resolute and determined to fight e-levy, the full course of it. We are in it for the long haul. It is no longer a matter to be discussed anywhere. We are not for it and we’ll not be for it.”

“We remain resolute and determined to fight e-levy, the full course of it. We are in it for the long haul. It is no longer a matter to be discussed anywhere. We are not for it and we’ll not be for it,” said Haruna Iddrisu, minority leader in Parliament, in an address to the press last month.

Deputy Majority Leader Alexander Afenyo-Markin sees it as a ploy by the minority to stall progress.

“As a majority, we can’t be cajoled into pettiness because we see this as a strategy by the minority — as it were — to create a standoff,” he said.

Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta argued that the tax would raise about $1.15 billion in 2022, ensuring that the country moves toward “a more sustainable debt level,” he said.

It would also ensure that Ghana has “revenues to sustainably invest in entrepreneurship, youth employment, cybersecurity, digital and road infrastructure,” he said a few days ago in Accra to the press.

He said the tax is a way for all Ghanaians to “help support their country and grow this economy.”

The mobile money boom

Many African economies continue to reel from the impact of COVID-19.

But since the start of the pandemic, global mobile money transactions have boomed, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, which represents 43% of all new accounts, according to the Global System for Mobile Communications Association.

Registered mobile money accounts in Africa grew 12% to 562 million in 2020, while monthly active accounts were 161 million — an 18% increase, according to the 2021 State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money.

Global daily mobile transactions exceeded $2 billion for the first time in 2021 and may surpass $3 billion a day by the end of 2022, according to the report.

But excessive taxation on mobile phone-based transactions could potentially reverse the gains for financial inclusion, according to a Foresight Africa 2019 report.

African countries must take a careful look at cost-benefit analyses before implementing a mobile money tax, the report said. Without fair tax policies, it warned, the incentive to use cash instead of mobile money may reverse advances in an increasingly cashless, digitized economy.

Ken Ashigbe, CEO of the Ghana Chamber of Telecommunications, said a lower tax rate of 0.25% or 0.5% might have been better.

“What has happened in other countries is that when these things have been allowed to happen, you find out that people have gone back to cash.”

“What has happened in other countries is that when these things have been allowed to happen, you find out that people have gone back to cash,” he said.

Back at the telecommunications shop in suburban Accra, Salormey Ayertey agreed. She believes a downward adjustment of the tax will help prevent her business from collapsing.

“If they reduce it, it will actually help us. It means people will still come here to do mobile money and my business will be saved,” she said.

A vote on the tax resumes in parliament this week. If passed, the tax would go into effect next month.