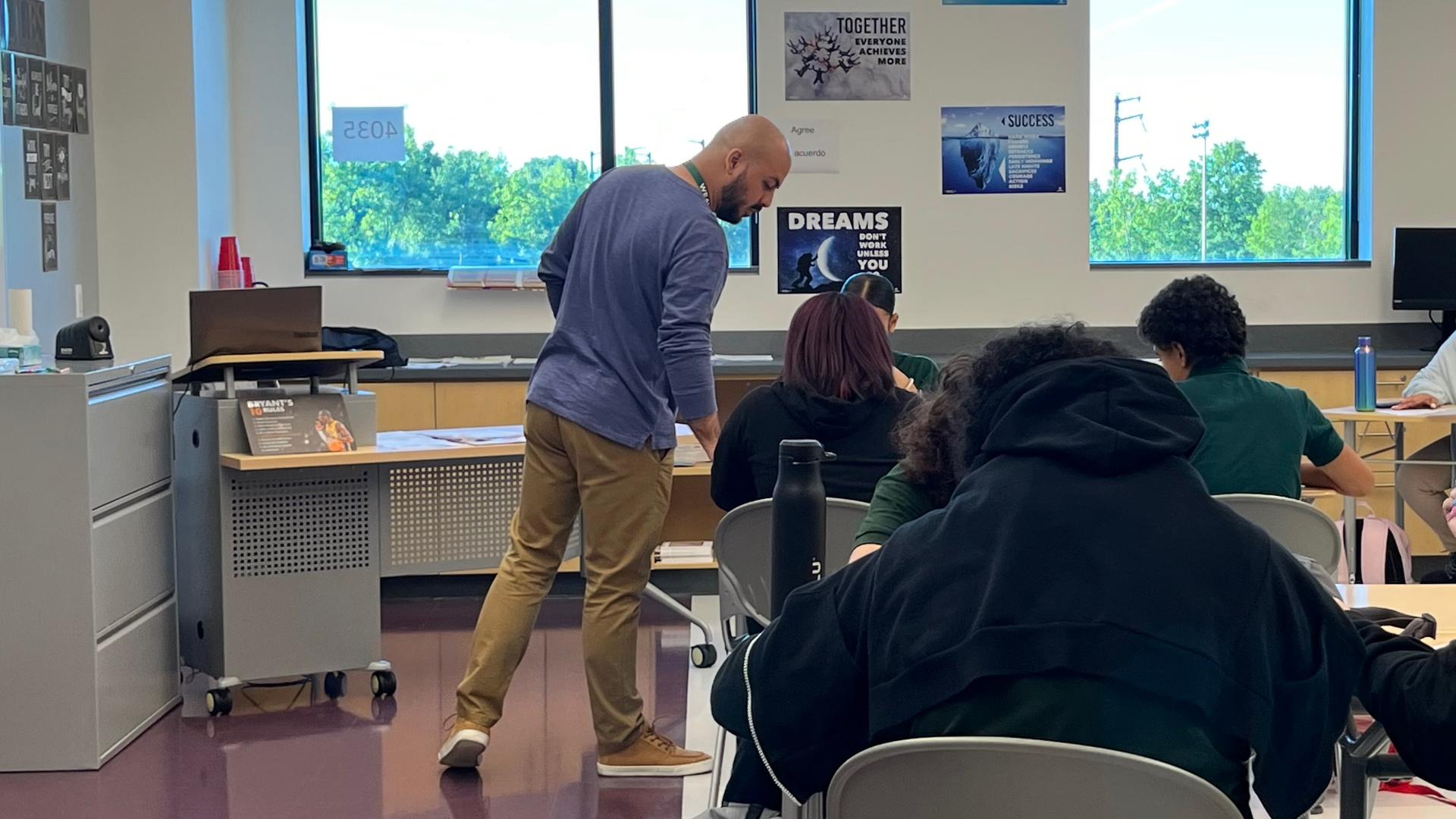

It’s the first week of class for US history teacher Marcos Gabriel Valentin-Ortiz at Weaver High School in Hartford, Connecticut.

The 33-year-old used to think he would never leave his native Puerto Rico. But after an offer to more than triple his salary, plus help with housing and a signing bonus, he is one of 16 teachers who relocated this school year to Hartford to teach in the city’s public schools.

He said that he’s enjoying his new city and his job, but it’s been an adjustment.

“Starting at Weaver has been a challenge because of all the [new] process of how things are done in this school or culture,” said Valentin-Ortiz, who teaches freshmen. “Getting to know the curriculum, getting to know the students and their different cultures. So, my first day was like a shock.”

Hartford Public Schools have over 17,000 students, and more than 1 in 5 students in the district are English-language learners. Also, more than half of the population is Hispanic or Latino, according to district information.

So, to respond to the needs of Spanish-speaking children, the Hartford Public Schools decided to recruit teachers directly from Puerto Rico as part of the Paso a Paso Puerto Rico Recruitment Program (“Step By Step”).

The school district initially brought two Puerto Rican teachers to the district in 2021 when it piloted the program.

Hartford Superintendent Leslie Torres-Rodriguez said that the district is facing an overall teacher shortage, currently operating with only 55% of its staff.

“So, this is a novel approach to help Puerto Rican bilingual teaching talent gain certification in Connecticut, and specifically, bolster the Hartford Public Schools teaching force,” Torres-Rodriguez said.

Research shows that academic outcomes for English-language learners are better when students are first taught in their native language and English.

With teachers retiring and fewer students entering the teaching profession in the US, Torres-Rodriguez said it just made sense to look to Puerto Rico for teachers.

“Since 2010, enrollment nationally in teacher prep programs has declined by a third,” Torres-Rodriguez said.

Hartford’s predicament is in line with other districts across the country.

All over the US, local districts are experiencing bilingual teacher shortages. It’s estimated that there are about 5 million students who have limited English proficiency enrolled throughout the nation’s public schools.

The district worked closely with Daniel Diaz, a consultant who’s been recruiting teachers from Puerto Rico for 15 years.

He said the greatest advantage for these teachers is their citizenship status — they’re American citizens, he said.

That allows these teachers to avoid the J-1 Visa process, which was created to let foreign nationals teach or study in the United States.

“We don’t have to go through the J-1 Visa,” Diaz said. “The teachers from Puerto Rico come here to stay.”

Making a living on the US mainland

Adriana Beltran-Rodriguez is a TESOL teacher (Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages), at Michael D. Fox Elementary School in Hartford. That means she provides extra support to 230 students who have recently arrived from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, the US Virgin Islands and worldwide.

“I was interested in helping the students feel like they’re not completely alienated in the school,” she said. “For [students] to know that there’s someone that cares about them and wants them not only to succeed in English but to honor their culture and their language.”

Beltran-Rodriguez, a native of Puerto Rico, is a recent arrival herself after being recruited by the Hartford school district from the University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras before she graduated.

“In Puerto Rico, there are so many wonderful things about it. But the truth is, for teachers, it’s a really hard time,” Beltran-Rodriguez said.

After witnessing her own high school teachers struggle with the rising costs of living, she said, it wasn’t a hard decision for her to move to the US mainland.

On average, a one-bedroom apartment in San Juan, Puerto Rico, is the same cost of a one-bedroom in Hartford, roughly $1,500. But a public schoolteacher’s salary on the island is $21,000 a year compared to the $44,000 she’s making in Connecticut.

Brain drain in Puerto Rico

Carmen Bellido, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico in Mayaguez, said she worries that the higher pay and opportunities luring teachers to the US mainland could lead to a brain drain back on the island.

“It does concern all of us universities that have teacher preparation programs, that the intensive recruitment has also reduced the number of students who want to be teachers,” Bellido said.

Normally, she said, she would place roughly 120 students each semester into teaching training sites in Puerto Rico.

“This past semester, what we had was 32 student teachers in practice,” Bellido said.

Since Hurricane Maria hit the island in 2017, followed by a devastating earthquake and a global pandemic, college enrollment has dropped by 14%, according to the National Center on Education Statistics.

But Valentin-Ortiz said that feels that he made the right decision, though he misses home, his friends and the grandfather who raised him. Still, he believes this is his time to grow.

“I’m still adapting. Still learning. And that’s one of the things that I want … to learn new things and have an adventure,” Valentin-Ortiz said. “Hopefully, I survive that adventure by the end of the year.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!