Mohamed al-Aweis describes the day his twins were born as one of the best days of his life.

His sons, Jad and Iyad, came into this world five years ago, amid war and chaos in Idlib province, in northwestern Syria. But for the Aweis family, this was a moment of celebration — joy and hope.

When doctors delivered his sons at a maternity hospital in Kafr Takharim, though, Aweis said, there was a problem.

“No oxygen. They didn’t give them sufficient oxygen.”

“No oxygen,” he told The World through a translator. “They didn’t give them sufficient oxygen.”

Related: Displaced Syrians in Turkey say Syria’s elections are a sham

Also, there had been bombings in the areas surrounding the hospital over the past few days. The doctors said it was not safe for Aweis and his family to stay there. They urged him to take his wife and babies home immediately.

Sadly, it’s stories like theirs that have become all too common in Syria, where a decade of war has severely impacted the health care system. Only 64% of hospitals across the country are functioning, according to a report by the International Rescue Committee published last March. In addition, 70% of the health care workers have fled the country.

Aweis wasn’t himself allowed in the delivery room, he said, but the hospital didn’t have the equipment needed to deliver oxygen to Jad. Doctors later told Aweis that his son needed at least one extra week of care at the hospital.

Related: This center in Turkey was a refuge for Syrian youth. The pandemic shut it down.

As the years went on, Aweis said, it became clear that Jad couldn’t walk. While his twin brother took steps confidently, Jad stumbled and quickly fell down.

Doctors in Turkey — where Aweis lives now with Jad — diagnosed his son with cerebral palsy. They said it was caused by the lack of oxygen at birth and that it was preventable, Aweis said.

The family was devastated.

‘No ICU doctors’

In many ways, the conditions are even worse in Idlib, the last part of Syria not under rebel control.

Fighting in other parts of the country has sent about 3 million people to Idlib, according to the UN. Most of the displaced people live in camps near the border with Turkey.

There is only one official and operational border crossing where humanitarian aid can get in. And hospitals come under frequent attack, even as recently as March, according to the UN.

That means doctors who are still working in Syria must deal with scenarios they are not trained for.

“We don’t have a single [intensive care unit] doctor in Idlib. Yes, we don’t have a single ICU doctor. There is no ICU specialist in Idlib. Full stop.”

“We don’t have a single [intensive care unit] doctor in Idlib. Yes, we don’t have a single ICU doctor. There is no ICU specialist in Idlib. Full stop,” said Dr. Shajul Islam, who works at a hospital in Idlib.

In a video he posted online last month, Islam explained what he was up against when faced with a newborn with complications.

Related: Syrian children in Lebanon are ‘being robbed of their futures’

“I’m on my phone frantically … who do I message? Who do I call?” he said. “Someone needs to help me. This child’s heart stopped, like, two times in the ICU. We’re doing resuscitation. Ventilator … OK. OMG, how do I set the ventilator for neonate?”

Sometimes, doctors in Idlib send critically ill patients to medical centers over the border in Turkey. But that day, Islam said, he didn’t think the baby would survive the roughly two-hour journey. She died at the hospital, he said.

Many doctors have left Idlib because of the war, Islam goes on to explain in the video. Those few who remain are mostly junior physicians.

“We never had that luxury in this war zone to specialize in one thing,” he said. “We [were] always a jack-of-all-trades when it comes to medicine. We had to be. Because we never had enough doctors.”

‘I will do whatever it takes to see him walk’

Aweis brought Jad to Turkey almost two years ago — in the hopes of getting him fitted with orthotic leg braces.

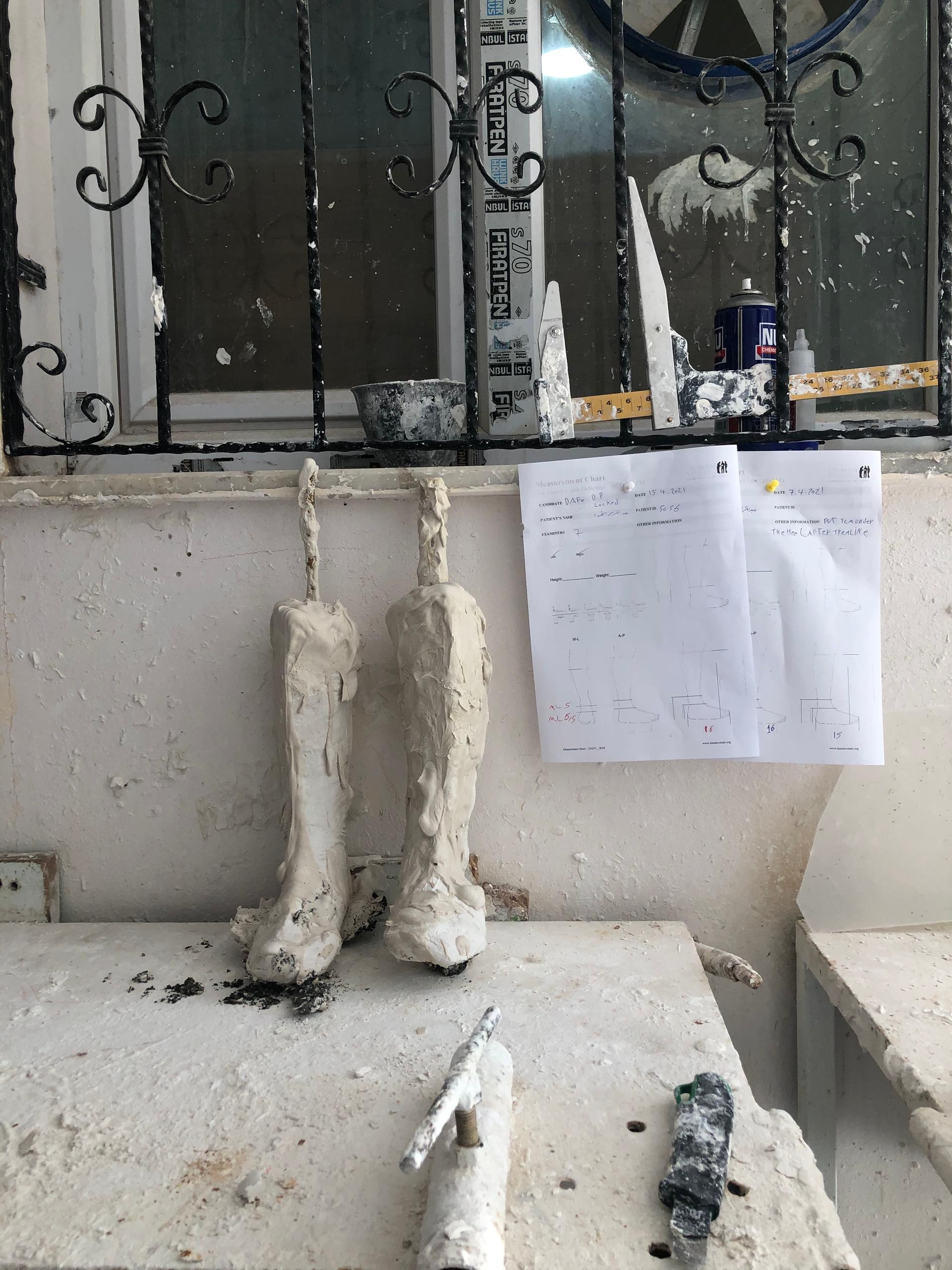

The World met them at a prosthetic limbs center in Reyhanli, a city on the border between Syria and Turkey. The National Syrian Project for Prosthetic Limbs was started in 2012 by a group of Syrian doctors with the goal of helping war-affected Syrians get prosthetic body parts.

Jad sat on a bed, his legs dangling on the side as specialists took measurements. They then covered his legs in white plaster.

Mohamed al-Tamer, who works at the center, explained that the plan is to make a temporary cast for Jad, which will be used later to make the braces.

But the 5-year-old seemed frustrated and didn’t want to sit still. His dad tried to help by asking him to say his name. At first, Jad insisted he didn’t know his name. But soon, he not only repeated his name but also started singing.

Related: Turkey announces full lockdown ahead of Eid celebrations

It will take several more sessions like this for Jad to get fitted with the braces.

Aweis said they have been in Turkey for almost two years now. His wife and five other children are in Syria because they can’t afford for the whole family to be in Turkey.

“I can’t work here because who is going to take care of Jad?”

“I can’t work here because who is going to take care of Jad?” Aweis said.

Crossing back to Syria has its own complications. He would have to get new permissions and pay for transportation.

But for Aweis, nothing is more important than seeing his son walk.

He said he will be at the center no matter how many more sessions it will take.