Saad Chouihna, 33, said that before the war broke out in Syria, his father owned one of the country’s top plastics factories in Aleppo, which manufactured containers for medical and cosmetic use.

“My father used to tell me how difficult it was when he started the factory in the 1980s,” Chouihna recalled. “He knew nothing about this business but he traveled to Italy and China to learn about the machines.”

Related: Turkey announces full lockdown ahead of Eid celebrations

The business got off the ground and did well. But the war took it all away.

“The government forces burned our factory, all the raw materials, all the spare parts. We lost more than $2 million.”

“The government forces burned our factory, all the raw materials, all the spare parts. We lost more than $2 million,” said Chouihna, who moved to Turkey before the 2011 uprisings to study. The rest of the family initially stayed in Syria, but later fled to Turkey, as well.

A decade of war has had a profound impact on the lives of millions of Syrians like Chouihna. His family survived physically, he said, but the mental and emotional toll has been high.

Now, as Syria prepares for a presidential election on May 26, Chouihna and many others displaced by the war are faced with more pain and exclusion from the process. Most don’t want to support a regime that upended their lives. Some also fear going to a Syrian consulate to vote and end up being arrested. And many don’t believe the election has any legitimacy at all.

Related: This center in Turkey was a refuge for Syrian youth. The pandemic shut it down.

“We already know who’s going to win,” Chouihna said.

Not a free or fair process

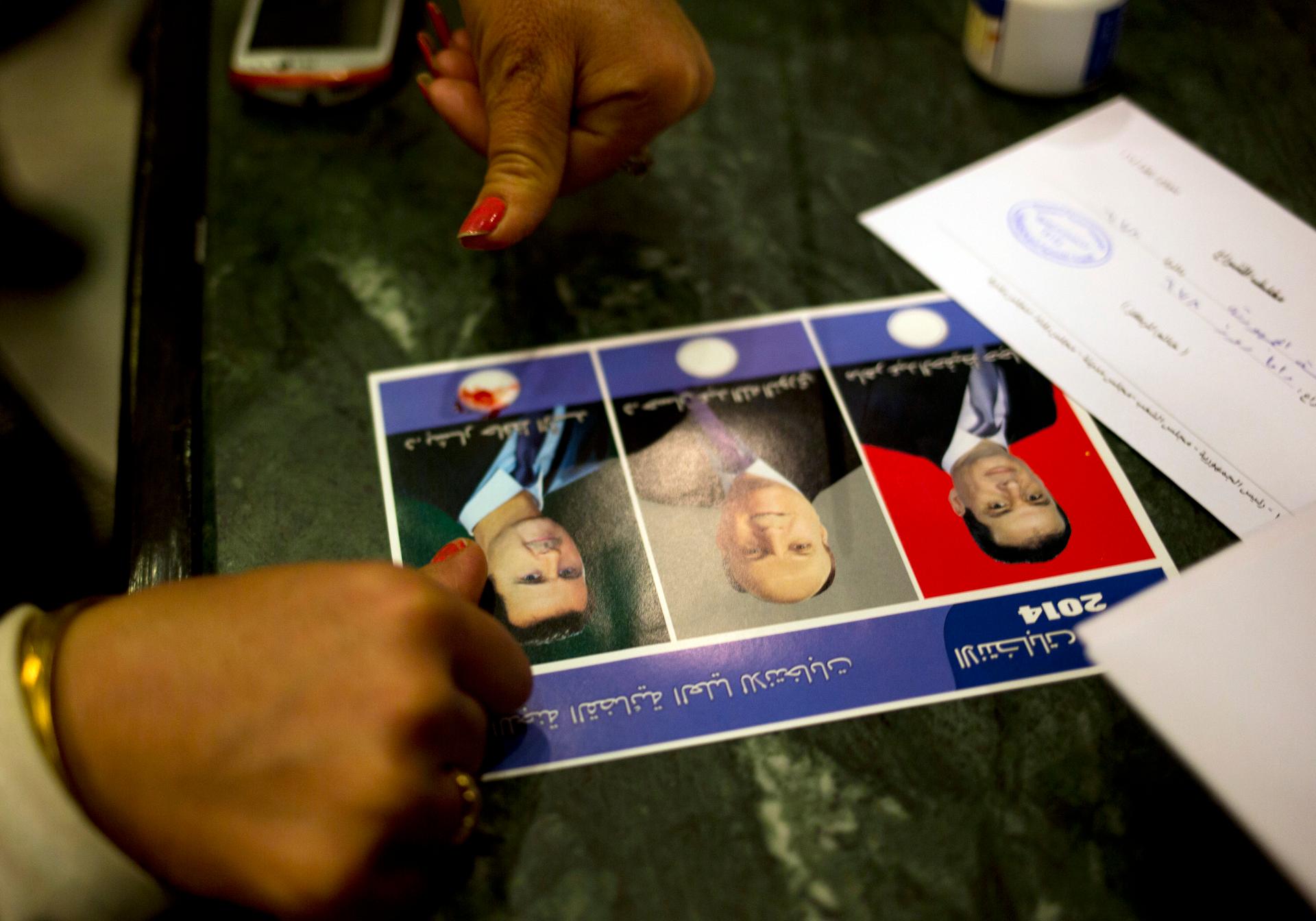

Syria’s state media reported on Monday that the country’s Supreme Constitutional Court has accepted three applications out of 51 for candidacy. President Bashar al-Assad was chosen along with two other men, Abdullah Salloum Abdullah and Mahmoud Ahmad Marie.

Seven women candidates had applied but were rejected by the court, stating that they did not meet the constitutional and legal requirements.

The UN and others have pointed out that it will not be a free or fair process.

Related: Afghans who fled to Turkey are worried — and hopeful — about the prospect of peace at home

“We know the Assad regime will attempt to use the Syrian presidential election this May to legitimize its own rule,” Linda Thomas-Greenfield, US ambassador to the UN, said last March.

“Do not be fooled. These elections will neither be free nor fair and will not be representative of the Syrian people.”

“Do not be fooled. These elections will neither be free nor fair and will not be representative of the Syrian people,” she added.

Assad won nearly 90% of the votes in the 2014 elections and is widely expected to win a fourth, 7-year term. He has held power since 2000, when he took over after the death of his father, who ran the country for 30 years.

Although Syria began allowing multicandidate voting in the 2014 elections, competition with Assad was symbolic and seen by opposition and Western countries as a sham designed to give the incumbent president the veneer of legitimacy.

The international community is unlikely to recognize the legitimacy of the upcoming elections. According to the UN resolution for a political resolution of the conflict in Syria, a new constitution is supposed to be drafted and approved in a public referendum before UN-monitored presidential elections are to take place. But little progress has been made on the drafting committee and Assad continues to have the backing of Russia and Iran.

Related: Syrian children in Lebanon are ‘being robbed of their futures’

In March, the Biden administration said it will not recognize the result of Syria’s presidential election unless the voting is free, fair, supervised by the United Nations and represents all of Syrian society.

‘A brutal dictator’

On the Syrian side of the wall that separates the two countries, millions of people remain displaced. They live in camps after Syrian government forces took over their towns with the help of Russia and Iran.

Over 80% of camp residents are women, children and elderly, according to the UN.

On the Turkish side, the occasional military vehicle passes by — a reminder of the tense atmosphere around here. Turkish forces have occupied parts of northern Syria since 2019.

Forty-year-old Samer Haj Khalid was displaced from his home in Idlib at the start of the war in 2011.

For Haj Khalid, like many Syrians here, the price of this war has been too high and even though Assad controls most of the country today, to them, he is no more than a brutal dictator.

Syrian TV encouraged those living abroad to register to vote on May 20. But Haj Khalid won’t be casting a ballot. He doesn’t see the point. His country is in ruins from the war, he said, and the man who led it to this point is running again.

Today, Haj Khalid leads a relatively calm life in Turkey. But he and his family had to abandon their home and farm in Idlib 10 years ago because of the war.

“There were tanks on the ground and planes in the skies,” Haj Khalid said.

They fled to the Turkish border with the clothes on their backs.

The Turkish government placed the family in a refugee camp on the Syria-Turkey border for a year.

Later, Haj Khalid was able to find work as a farmer through a program run by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

“I will only consider going back to Syria if Assad was removed from power. If the UN puts him in jail and somebody replaces him in Syria. Then, there is a hope that I will go back.”

“I will only consider going back to Syria if Assad was removed from power,” he said. “If the UN puts him in jail and somebody replaces him in Syria. Then, there is a hope that I will go back.”

“People are dying and starving in Syria. What will I do there?”

‘No dictator, no regime will last forever’

Chouihna, in Turkey, said that after the family’s factory was targeted, the Syrian Armed Forces came for their orchards — thousands of olive and pistachio trees and grapevines that his grandfather had planted were burned down to ashes.

He said his father was devastated.

“We were worried about him,” he said.

But he wasn’t one to give up. Chouihna said his father went back and replanted some 5,000 trees. His father would go to Aleppo often to check on the olives, pistachios and grapes. Five months ago, when Chouihna’s father went to the orchards for the harvest, he got COVID-19 and died in Syria.

Chouihna said his father is buried on the land he loved.

“He never left Syria. His soul was there.”

“He never left Syria,” he said. “His soul was there.”

In some ways, Chouihna is keeping his father’s memory alive in his work, too. He started a plastic factory in Gaziantep, Turkey.

The factory is doing well despite the pandemic.

“My dad always encouraged me to work hard, to read more, to be physically active and take care of the nature.”

Although Chouihna has established himself in Turkey, he’s sure about one thing — that he will go back to Syria one day.

When asked if this is realistic, Chouihna said, “My father when he planted the trees, he didn’t plant it for himself. He planted it for us. And maybe we can’t go to Syria now […] but maybe our children will do this. Look at the history and read about the history, no dictator, no regime will last forever.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!