Scientists link Earth’s magnetic reversals to changes in planet’s life and climate

As odd as it may seem, Earth’s magnetic poles are not fixed. They wander around a bit and, throughout Earth’s history, they have even entirely reversed themselves. Now scientists have evidence for how these magnetic flips could impact life on Earth.

Scientists don’t know what causes magnetic reversals to happen, says Carolyn Gramling, a climate writer at Science News.

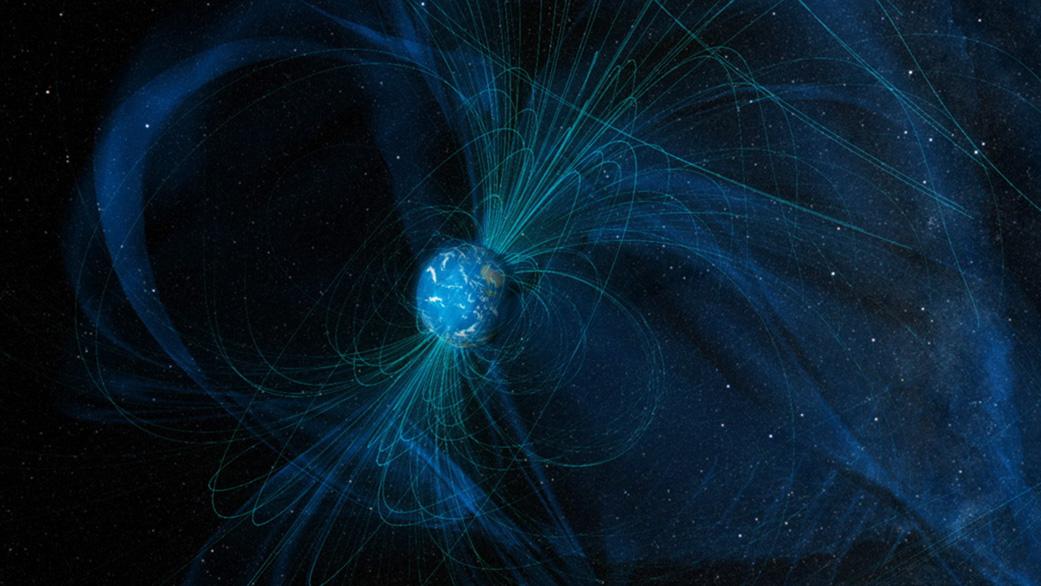

“What we do know,” she says, “is that Earth has a metallic core. It has a liquid metal outer core and a solid metal inner core made of iron and nickel. And the interaction between these two cores and the flow of the minerals within them…generates an electric current, which generates a [magnetic] field.”

“Throughout Earth’s history, for millions and millions of years, we know that [Earth’s] poles have occasionally reversed themselves, so that the north pole becomes south and south becomes north.”

This magnetic field is like a “giant bar magnet at the center of the planet” that has a north and south pole, Gramling says. “And throughout Earth’s history, for millions and millions of years, we know that those poles have occasionally reversed themselves, so that the north pole becomes south and south becomes north.”

A fossilized tree discovered in New Zealand has helped researchers date one of these magnetic flips to about 41,000 years ago, a time when Earth also saw megafauna extinctions, climatic changes and even a rise in cave art.

Related: The history of the world is written in tree rings

Scientists call this particular magnetic reversal the Laschamps excursion. They can date this event by studying the rock record. “When rocks are forming, the tiny magnetic minerals that are inside those rocks can orient themselves to align with the current magnetic field, whichever way it’s going,” Gramling explains.

The Laschamps excursion lasted only a few hundred years, but scientists are interested in it because they think it might help them figure out how a magnetic reversal might have affected creatures living on Earth at the time.

Prior to a magnetic reversal, there’s a period when the poles are “sort of getting ready to switch,” Gramling says. During this period, the Earth’s magnetic field weakens, allowing more solar radiation to hit Earth, which can affect life on the planet.

“So the big danger period was…actually around 42,000 years ago, right before the reversal actually happened,” Gramling explains.

Scientists know that some “large, charismatic animals” had gone extinct at this time,” and that, “weirdly, it was right around this time that you saw this big uptick in cave art, in humans painting in caves,” Gramling says. “We knew that there were some climatic shifts that occurred around this time. But being able to link them to this event is the real trick.”

In 2019, Gramling says, a group of scientists found the “Rosetta Stone” that might link all of these events: an ancient tree that had been dug out of a peat bog in New Zealand.

Some of these ancient coniferous trees are still living in New Zealand today and their antecedents have been around since the Jurassic period, millions of years ago, Gramling says. The particular trees in this peat bog date to about 50,000 years ago.

A lot of giant old trunks, some of them several meters in diameter, are buried in these bogs and have been preserved there, Gramling says. People dig them out for selfish purposes — to use them for tabletops or pillars, for example — but they’re important to science because they contain a record of climatic events.

So researchers knew that if anything could possibly tell them what happened to the climate about 42,000 years ago — it might be this tree.

The researchers examined the rings of the tree to look for changes in the amount of carbon-14 over a period of years, Gramling explains. Carbon-14 is useful not only for dating things, but because the interaction of cosmic rays with molecules in the atmosphere produces a lot of it. And when the Earth has a weakened magnetic field, more cosmic rays hit the planet.

The scientists indeed found a large spike in carbon-14 in the tree, which they could then compare with the rock record that indicated a magnetic reversal. Now, Gramling notes, they could say, “‘Okay, we know these things were coincident. Isn’t that interesting?’”

In addition, there is the documented rise in cave art right about 41,000-42,000 years ago, Gramling points out. Scientists have also found paintings from this time with outlined handprints made from red ochre. As it happens, some Indigenous communities, even today, use red ochre as a sunscreen.

“Is it possible that you have this extra UV radiation coming in and all of a sudden you have humans in caves more, making this cave art with the red ochre paint? Is it possible that that could have been because they were taking shelter from the increased radiation from the sun during that time?”

“So, is it possible that you have this extra UV radiation coming in and all of a sudden you have humans in caves more, making this cave art with the red ochre paint,” Gramling asks. “Is it possible that that could have been because they were taking shelter from the increased radiation from the sun during that time?”

As it happens, about 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals went extinct. Could the magnetic reversal be connected with this event, too?

“With the rapidly changing climate, it may be that [Homo sapiens] were able to outcompete Neanderthals for whatever resources were becoming more scant,” Gramling suggests.

“And of course, there were these megafauna extinctions, particularly in Australia. They note, for example, there was a giant kangaroo that went extinct around that time, and some other strange Australian animals. There was a type of carnivorous marsupial, sometimes called a pouch lion, that went extinct, [and] a bucktoothed wombat that stood about 6-feet tall. So, all of these things were happening right around that same time.”

This article is based on an interveiw that aired on Living on Earth from PRX