For many in Pakistan, the death of a man known as the country’s “father of human rights” signals the end of an era.

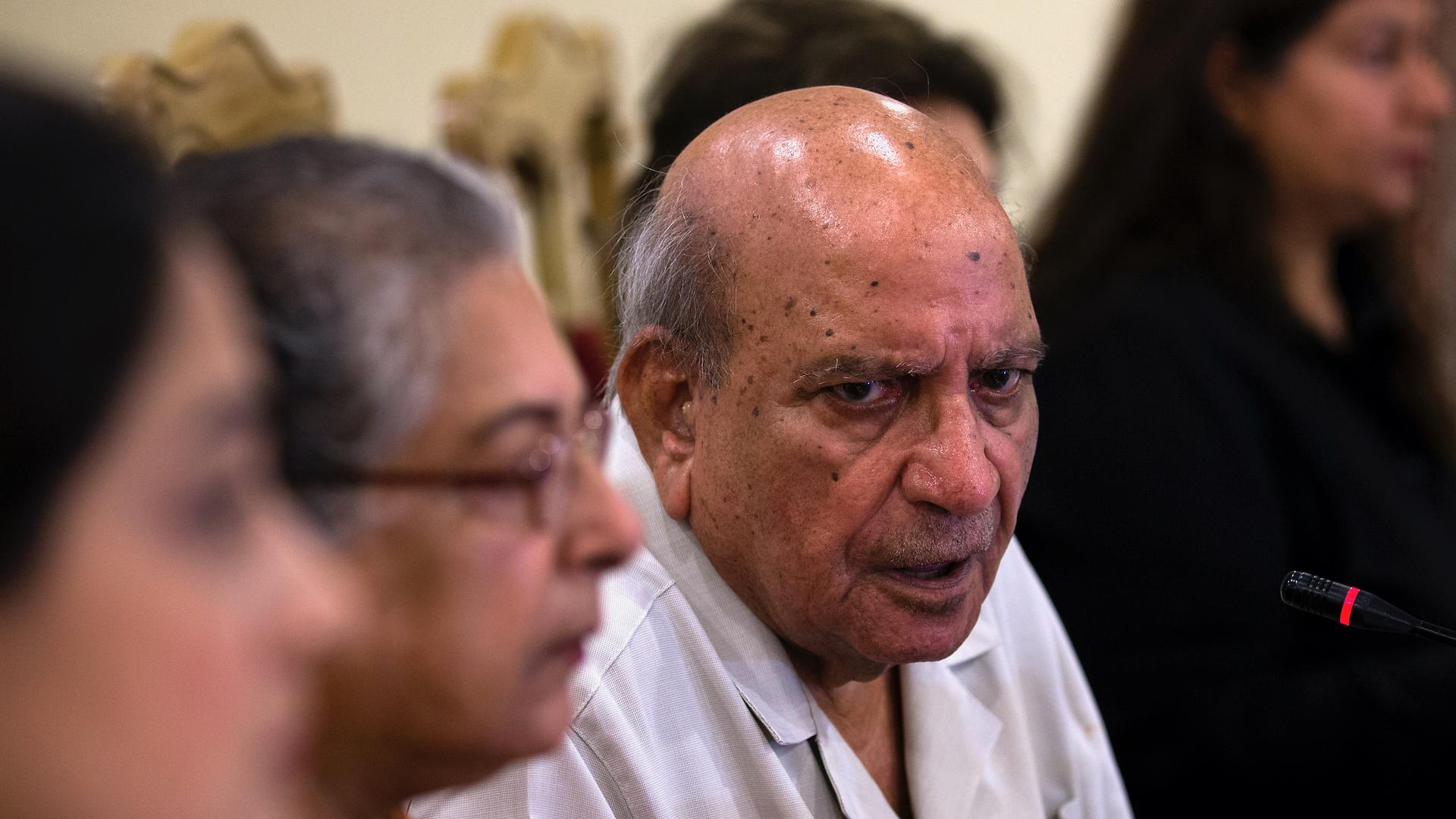

I.A. Rehman, a prominent activist and co-founder of the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, has died at the age of 90 of natural causes.

Rehman opposed dictators, supported secular democracy and fought for the rights of religious minorities and women.

“These are subjects that if you talk openly about in Pakistan, you’re a target. You can be killed. You can be attacked.”

“These are subjects that if you talk openly about in Pakistan, you’re a target. You can be killed. You can be attacked,” said Taha Siddiqui, a journalist who spent time with Rehman in Pakistan.

Related: Powerful countries break their silence on Egypt’s human rights abuses

Siddiqui was attacked in 2018 and forced to flee. Now, he lives in Paris. Siddiqui said that, despite the danger, Rehman was one of the most persistent and vocal advocates for equality in Pakistan.

“For all of us, he was kind of a mentor and inspired all of us to be someone like him, especially because there are not many like him in Pakistan.”

Rehman was born in northern India to a family he later described as both secular and Muslim. His parents instilled in him a devotion to civil rights for all. Rehman said that as a high-schooler, he didn’t know the difference between Hindus and Muslims. But when he was 17, India went through partition, and his family migrated to Pakistan.

Related: A new US award honors anti-corruption advocates around the world

Rehman started writing for the Pakistan Times, a revered institution. He became part of a prominent group of journalists and human rights activists.

Marvi Sirmed’s father was also part of that group. She grew up with Rehman as an uncle.

“It was [the] early 1950s,” Sirmed said. “That was the era of ideologies.”

Sirmed said Rehman was part of the first generation of intellectuals and activists of the new nation of Pakistan, driven to preserve its founding ideals. Together with prominent human rights lawyer Asma Jahangir, Rehman co-founded the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, or HRCP. It remains a powerful force in the country.

“HRCP would not have been the kind of institution it is today had it not been for Rehman Uncle. It was like his baby.”

“HRCP would not have been the kind of institution it is today had it not been for Rehman Uncle,” Sirmed said. “It was like his baby.”

Sirmed — a human rights advocate herself — said Rehman helped preserve the ideas of freedom and human rights as Pakistanis adjusted to life under one dictator after another.

“We wouldn’t have known what is right and what is wrong because [in] my generation, the schools were working under oppression, the media had completely Islamized, the state was Islamized,” she said. “So, we wouldn’t have known the light of the truth had these people not been there.”

Related: UN Human Rights Council starts work to address a ‘pandemic of human rights abuses’

Rehman was a columnist for the English-language newspaper Dawn. In recent years, he argued that the Pakistani government was using its nuclear weapons to hold on to political power. Rehman also bemoaned the disappearances and detentions of journalists and human rights activists.

“Things have changed a lot, and he was very upset about it,” Sirmed said. “I haven’t seen him so perturbed about the tactics of the state, ever.”

Rehman died on Monday. Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi tweeted that the country had lost “a true icon” who had championed “tolerance, inclusion, equality and dignity.”

Saroop Ijaz of Human Rights Watch called Rehman Pakistan’s “father” of human rights.

Rehman’s death comes three years after that of his Human Rights Commission co-founder, Jahangir. The loss of these two towering figures, Sirmed said, has been devastating.

Related: Public art honoring Egyptian American Moustafa Kassem sends universal human rights message

“We have been dreading this,” she said. “This whole generation — we were always taught that these people are so giant, what will we do without them?”

Siddiqui said it’s not easy for activists today to follow in their footsteps and stand up to the Pakistani government.

“We often talk about this in Pakistan — who are the next Asma Jahangirs or I.A. Rehmans?” he said. “And we don’t see any.”