To reach the area where a new refugee camp on Lesbos is expected to be built, it means driving through unmarked dirt roads and over deep puddles — so long as you have a vehicle that can make the journey.

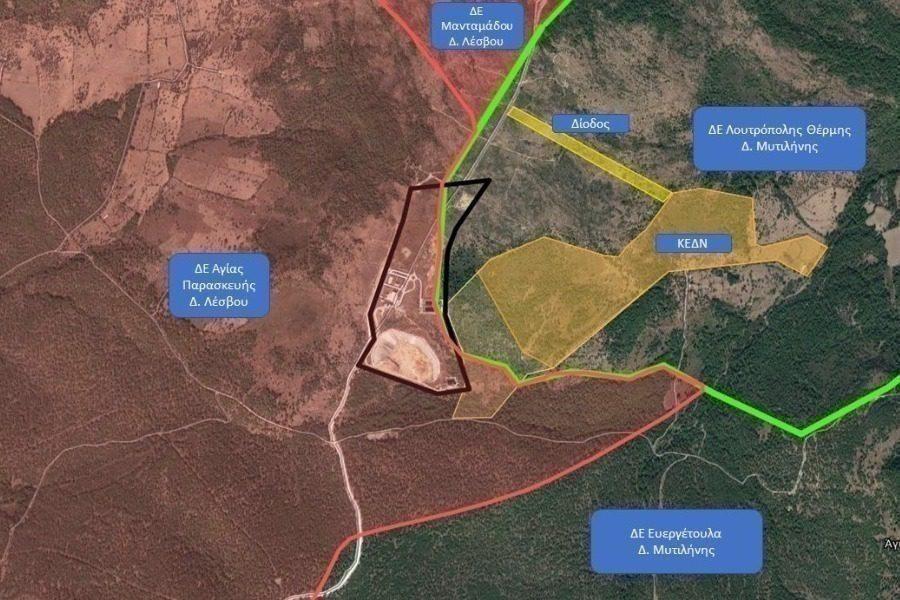

The site, about 20 miles north of the port city of Mytilene, is noted on a map that Greek officials shared with local media in the fall. On this part of the island, bounded by untouched forest and a landfill, seagulls feed on the trash, and the stench is overwhelming.

Work on the camp is expected to begin in the summer, according to Greek officials, and the goal is to have it done by the end of the year.

Related: Activists protest migrant facility plan in Greece: ‘Greek islands will not be turned to prisons’

Officials say the new facility will improve conditions for migrants and locals on the island. But some migrants and other observers say that the remote locale, so far away from any services and businesses, would make it even harder for refugees to find help — and stability.

That’s something that worries Morteza, a 16-year-old Afghan asylum-seeker who asked to only use his first name out of fear that it might affect his family’s asylum application.

“I don’t want to be in a prison. This island is a prison. Just let us go to another country.”

“I don’t want to be in a prison. This island is a prison. Just let us go to another country,” he said. “I just want to be free.”

Too remote?

Talk of building a closed reception facility for asylum-seekers who arrive on the island picked up last year after Moria camp, the main refugee camp on the island, was destroyed by fire.

Related: Greek police roll out new ‘smart’ devices that recognize faces and fingerprints

Migrants who were living in Moria were moved to a temporary tent facility on the island. Approximately 7,000 asylum-seekers and refugees live in tents at Mavrovouni camp, often called “Moria 2.0” because of conditions resembling the previous camp.

During a visit to the island last week, the European Union’s top immigration official announced 155 billion euros or more than $180 billion in funding for new migrant reception facilities on Lesbos and another island.

The new facilities would be equipped with containers, rather than tents, as well as electricity and facilities such as showers and toilets.

“It’s of the utmost importance that we don’t leave people in tents for another winter.”

“It’s of the utmost importance that we don’t leave people in tents for another winter,” said EU Home Affairs Commissioner Ylva Johnasson during her visit to the island last week.

Related: Greece ‘finally’ has its #MeToo moment

Sitting alongside Johansson at a press conference, Greek migration minister Notis Mitarakis said the new site for the camp was chosen because of its remote location.

“The goal of the creation of the new structures was to not be in urban centers. Not to be in the main towns, as is Mavrovouni camp [on Lesbos] today … A location was chosen that has a substantial distance from large settlements [heavily populated areas],” Mitarakis said.

“It’s in the middle of nowhere,” said Violeta Maria Dimitrakopoulou, an activist and researcher with Disinfaux Collective who’s lived on Lesbos for nearly a decade.

Life for asylum-seekers and refugees would be “very, very hard” if they’re moved to a remote part of the island, she said, because they would be isolated and unable to reach crucial services and activities.

Officials have said camp residents will be allowed to exit and reenter the camp, with some restrictions.

Dimitrakopoulou said a controlled entry and exit system may not be enough.

“But where [will] people go? In the forest? And do what?” Dimitrakopoulou pondered.

The camp that refugees and asylum-seekers are currently in is close to Mitylene, and people can walk to nearby markets, nongovernmental organization offices, doctors’ appointments and other services.

Related: In Greece, a clergyman’s death reignites communion spoon debate

“Of course, we want people to be close to services,” said Georgia Mitsika, who manages Lesbos operations for the International Rescue Committee, a nongovernmental organization on the island.

“We want them to be able to reach services anywhere. But we will support them when they need us, even if they are transferred.”

“We want them to be able to reach services anywhere. But we will support them when they need us, even if they are transferred,” Mitsika said.

The Greek Ministry for Migration and Asylum did not respond to a request for comment on concerns about the camp’s location.

A ‘golden prison’

Plans for a new migrant facility have also drawn backlash from the local community and from activists who say a camp is not the answer.

“What I’m afraid of the most is that they want to create a facility that seems to be more human,” said Clotilde Scolamiero with INTERSOS, a humanitarian organization that has provided emergency support to refugees on the island and is now offering mental health services.

That normalizes detention, she said, because “It seems much more humane. And you cannot say anymore that people are suffering … But it allows the idea that people … can stay for months or even years [and] end in a prison.”

She likened the camp with upgraded facilities such as showers to a “golden prison.” She and her organization are against refugee camps altogether.

“We believe that the European Union should manage immigration in a completely different way, toward integration, not toward confinement,” Scolamiero said.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!