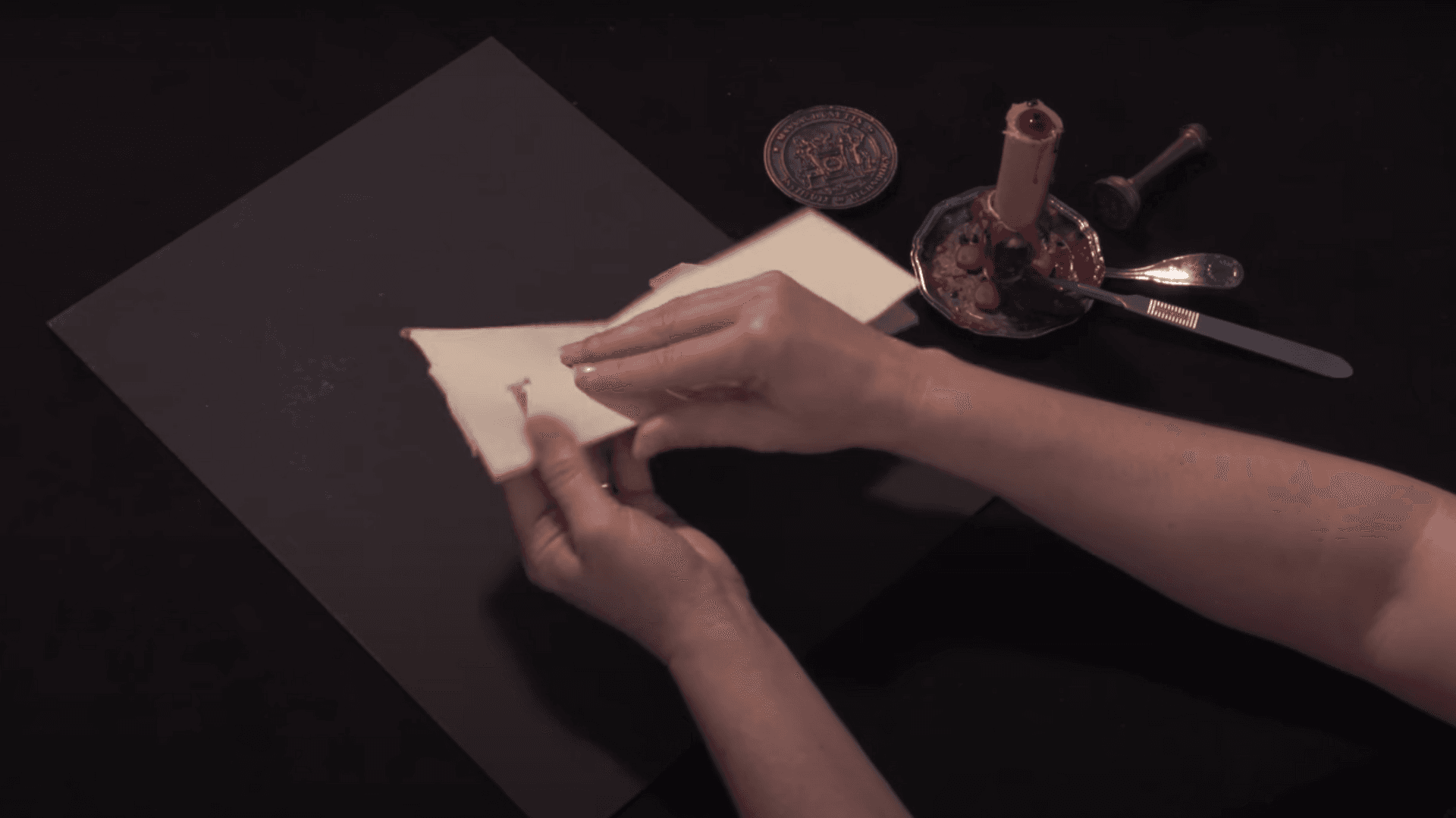

Ever since humans have been sending messages, they’ve devised ways to keep them secure from prying eyes. But before there was password protection or message encryption — before there were even “envelopes,” which were not mass produced until the 1800s — there was something known as “letterlocking.”

Related: Battle of the bums: Museums compete over best artistic behinds

Letterlocking, a term coined by MIT Libraries conservator Jana Dambrogio, is when a piece of paper is folded in such a way that it becomes its own envelope. Techniques range from a simple aerogram to more complex “locks” using interlocking pieces of paper.

Related: 245 years on, Jane Austen fans mark her birthday with virtual tours

In order to read the text of such letters, historians once had to slice them open or break their seals — that is, until now. Using high-tech scans and a specially designed computer algorithm, Dambrogio and a multidisciplinary team of researchers, a group called Unlocking History, were able to “virtually unfold” a letter written in the 1600s — without opening it.

“It felt like being teleported 1,000 years into the future. It was astonishing. We were speechless.”

“It felt like being teleported 1,000 years into the future. It was astonishing. We were speechless,” said Daniel Smith, a lecturer at King’s College London, who is part of the Unlocking History group, during a press conference this week explaining the group’s work. They published their findings in Nature Communications on Tuesday.

Related: The surprising cultural contributions of the 1918 influenza pandemic

The process begins with a high-resolution X-ray scan of the unopened letter. Then, an algorithm designed by computational scientists identifies and separates the layers of its folded pages. This allows researchers to read the text of the letter but also to see all of its crease patterns — in other words, to learn how it was folded, or locked.

“Letterlocking can be as unique as a signature. … Spies definitely used it in that way. King Charles I wrote to one of his women spies that she had to use a certain ‘lock’ and he knew [he] would know her by the folding of her paper.”

Those patterns can be quite revealing, according to Nadine Akkerman of Leiden University in the Netherlands, who studies early modern espionage.

“Letterlocking can be as unique as a signature,” she explained. “Spies definitely used it in that way. King Charles I wrote to one of his women spies that she had to use a certain ‘lock’ and he knew [that he] would know her by the folding of her paper.”

Some letterlocking techniques were so complicated that by opening the letter in question, you might destroy part of it in the process (some were even intentionally designed that way, to alert the recipient to potential tampering.) But with this new tool, researchers can read historic unopened letters and examine their letterlocking techniques while keeping the artifacts intact.

So, the moral of the story is: If you really don’t want anyone to read your letters — you should probably consider burning them.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?