How the Trump administration’s climate denial left its mark on the Arctic Council

A polar bear stands on the ice in the Franklin Strait in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.

This story was originally published by InsideClimate News.

For decades, through political tumult and changing global allegiances, the Arctic Council went about its business, producing groundbreaking scientific reports and hammering out binding agreements to ensure cooperation among its members and address climate change.

Even when diplomacy failed in other venues, the council, an international organization consisting of the eight countries that ring the Arctic Circle, was able to proceed with its work.

That ended, members of the council say, with the arrival of the Trump administration.

The shift in the Council was gradual at first, but by the second half of President Donald Trump’s term, his impacts were undeniable. The words “climate change” — or even references to the subject — became too controversial for inclusion in joint documents. Projects related to climate change proposed by other nations were shot down by US negotiators who knew there was no way their top leadership would be on board. Negotiations within the council failed to reach a deal.

The changes in the council illustrate the mark left by the administration’s climate denialism on international diplomatic efforts, one that some experts say will take time to undo.

“It’s a bad stain on the history of the Arctic Council,” said Adrianna Muir, who served as the State Department’s deputy senior arctic official from 2014 to 2018 and was a part of negotiations at the council.

In four years, the Trump administration sought to uproot the existing narrative about the Arctic and replace it with something more sinister.

“The line of thought expressed by the Trump administration was that the Arctic is no longer a zone of cooperation, but a zone of conflict and somewhere the US should seek to expand their influence at the expense of diplomacy and cooperation,” said Whit Sheard, the president of the Circumpolar Conservation Union.

Most glaring, Sheard said, was how little the Trump administration understood the region. Whether it was the administration’s misguided efforts to buy Greenland or the US Ambassador to Iceland’s attempt to carry a gun in a nation considered one of the safest in the world, there was a blatant lack of comprehension about Arctic culture, Sheard said.

“It was all an attempt to destabilize the Arctic,” he said, “and it has ultimately left the United States a much less important actor.”

A changing tune on climate

When Trump was elected, the United States was playing a central role in the Arctic Council.

Every two years, a different Arctic nation takes over as chair of the council, an opportunity for that country to set the agenda and showcase its presence in the region. The United States took over the chairmanship in the spring of 2015.

“We went into it knowing that there would be an election in the middle of the chairmanship,” Muir said. “And we had no ability to promise to any of our foreign interlocutors what that would mean.”

As Trump settled into the White House and made his cabinet appointments, the Arctic was not at the top of his to-do list. For some in the world of Arctic policy and research, that was a relief: In interviews at the time, experts working in the region said they planned to keep their heads down in the hope that their work could continue untouched for as long as possible.

At the State Department, though, they didn’t have that luxury.

In early 2017, the US chairmanship of the Council was nearing its end. Each two-year rotation ends with a ministerial meeting in April, which is often a big, splashy event, and it was the United States’ turn to host the gathering. The meeting normally ended in the release of a declaration, signed by all eight Arctic nations, that would signal what work had been accomplished over the past two years and what lay ahead.

The language for that document was already in circulation among the countries before Trump was inaugurated. For nearly two years, negotiators from each of the countries, along with indigenous groups, had been working out what the declaration would say. It would acknowledge the signing of the Paris Climate Treaty, summarize the findings of the Council’s scientific work on climate impacts in the region and commit the parties to implementing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

But much was unknown. With a climate-denying president and Rex Tillerson, former Exxon CEO, as his newly-appointed Secretary of State, would an Alaska-based ministerial meeting even take place?

Muir and her colleagues did all they could to get a memo to the top of the pile in Tillerson’s office, she said. “It basically needed to communicate: There’s this forum, and P.S., we’re chairing it and we’d like you to host it,” said Muir, who now is the deputy director of the Alaska branch of the Nature Conservancy.

As the weeks ticked by with no response from Tillerson’s office, other Arctic nations began reaching out to Julie Gourley, the State Department’s Senior Arctic Official, who had been handling negotiations with the council for more than a decade. The other countries needed to know: Was the meeting going to happen? And would Tillerson be there?

“I still recall the day the memo came back approved to our office from Secretary Tillerson with his commitment to host the meeting and chair it,” said Muir. “We did a happy dance. We literally got up and did a dance — a jig. It meant that all of the work we had been putting forward for the last two years could get a bright light shone on it.”

When it came time for the meeting, though, the administration got more involved. At the last minute, when the declaration’s language was thought to be finalized, the State Department sent over several proposed changes, each of which would eliminate or soften the language related to climate change.

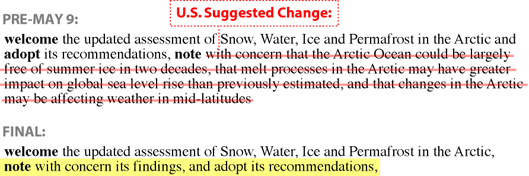

Those changes, shared with Inside Climate News in a leaked draft, clearly reflected the views of the new administration. One suggested change took out language encouraging the implementation of the Paris Agreement; another deleted the findings of a scientific report, including a concern that the Arctic Ocean might be free of sea ice in two decades and if that were the case, what impact that would have on both sea level rise and temperatures in mid-latitudes.

Some of the changes were accepted, others were tweaked to keep climate language in the declaration but make it softer. A reference to the scientific report remained, but the description of its findings was cut altogether.

When Tillerson signed the document and it was released to the public, many watchers of the Arctic Council felt relief — despite the new US administration, the document mentioned climate change and the Paris Agreement, among other topics that were now considered controversial.

But to those who had seen the earlier language, it represented a compromise between what could have been and what the US had demanded. It was a sign of things to come.

‘A constant push to make things vanilla’

After the US ministerial meeting in April 2017, the chairmanship passed to Finland, and for a little while, the State Department team was able to work without interference.

“We were sort of self-monitoring and trying not to get too climate-friendly,” said Gourley. As the Finnish chairmanship progressed and they began work on the next group declaration, it was up to Gourley to make sure that whatever was written would be something a Trump State Department — now led by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo — would sign. “We were just trying to keep the messaging low key,” Gourley said.

Gourley was in a challenging position. The Nordic countries, in particular, wanted the council to have a strong stance on climate change, she said, as did the representatives from the Indigenous groups. “It was this constant push to make things vanilla,” she said. “It was this three-prong debate about how to make it pass muster with the Trump administration.”

There were times, she said, that members of the group would raise their hands and propose a project related to climate change — a topic that’s never far from mind when talking about the Arctic — but the project would be quashed by the US delegation. “Someone would say, this is something we need to alert the world about that is happening, and I’d have to say no. It was pretty awful,” she said.

And it was about to get worse.

A few months before Finland’s ministerial, the speech writers at the State Department “started to wake up and realize this was an opportunity,” Gourley said. Initially, her staff worked with the speech writers. “We thought maybe it would go kind of well, but then suddenly they cut us out,” she said.

As Gourley’s group headed to Finland for the ministerial in May 2019, Pompeo tapped Manisha Singh, then the acting undersecretary of state for economic and business affairs, to go to the meeting and “straighten things out,” Gourley said.

“She waltzed in and completely destroyed everything,” Gourley said. Despite having no background in climate change or in the region, Singh made significant changes at the last minute to the declaration — removing mentions of ocean acidification, which poses an imminent threat to the Arctic, and other climate-related issues.

At one point, Gourley said, she and her staff were locked out of the room their delegation had been assigned so that Singh could call Washington in private. “We had no idea what was going on,” Gourley said. When Singh came out of the room, she delivered the news to the negotiators: The United States would not be signing the document. For the first time since the council was established in 1996, there would be no Arctic Council declaration.

“It was the worst professional experience of my entire 30 years,” said Gourley. Years of diplomatic wrangling — for nothing.

The State Department did not respond to questions about Singh’s involvement with the Arctic Council. But after four years of denying the impact of climate change in the Arctic and promoting oil and gas company interests, a department spokesperson — perhaps reflecting the views of the incoming Biden administration — issued a statement that included the following: “The United States envisions the Arctic region as one that is free of conflict, where nations act responsibly, and where economic and energy resources are developed in a sustainable, transparent manner that also respects the environment and the interests and cultures of indigenous peoples. The United States recognizes the climate vulnerabilities and risks that the Arctic faces because of its unique circumstances, including from changes in snow and ice cover.”

After the failed negotiations at the Finland meeting, the situation further deteriorated, Gourley said.

At a side event she and her team were required to attend, Pompeo gave a speech lambasting Arctic allies Russia and Canada, as well as China, which has observer status in the Arctic Council.

Pompeo referred to the region as a land of “opportunity and abundance,” one replete with untapped reserves of oil, gas, uranium, gold, fish and rare earth minerals. No longer did the Arctic Council have the “luxury” of focusing on scientific collaboration, cultural matters and environmental research, he said. As the sea ice gives way to open water in the North, “we’re entering a new age of strategic engagement in the Arctic, complete with new threats to Arctic interests and real estate,” said Pompeo.

Sitting in the audience, with representatives from the countries Pompeo was attacking, Gourley said, “We are all dumbstruck.” Her Russian counterpart came to find her afterward to see if she knew why Pompeo had lashed out in that way. She learned through other Arctic partners that the Chinese representatives were “very unhappy.” The Canadians, understated but clearly displeased, told her, “Oh, that was an interesting speech.”

Sheard, of the Circumpolar Conservation Union, was at the talk as well. An American who attends council meetings with observer status, Sheard described sitting through Pompeo’s talk and feeling the “most embarrassed I’ve been for our country since I started working in the Arctic Council in the mid-2000s.” He said the “attempt to create a dialogue around a great Arctic competition is an attempt to create a self-fulfilling prophecy.” After the talk, he added, a representative from another country offered to let Sheard wear a pin with that nation’s flag on it, so he wouldn’t have to hang his head.

At the end of the event, Gourley’s colleagues from the other Arctic countries took her out for dinner to celebrate her final Arctic Council ministerial — she was about to retire. They told her that they felt bad about the position she had been put in, and wanted to celebrate her years of working with the group.

After the dinner, she said, “Me and my team went out and had a bender.”

A need for mending fences

Now, as President-elect Joe Biden steps into the White House, there will be some diplomatic fences to mend.

“This push to isolate and bedevil China has pushed them closer to Russia,” Sheard said of the Arctic Council. “That leads to more cooperation in the Arctic that would actually threaten US and economic power interests, in terms of keeping us from being a part of those plans for the Russian and Chinese ambitions.”

Beyond that, he said, the Arctic Council has always been the premiere forum for cooperation and respect for Indigenous values. “I think the fear of some is that Trump’s attempt to undermine this might have lasting impacts for the good work that’s been done over 20 to 30 years with respect to cooperation and working with indigenous groups,” Sheard said.

The new Biden administration will be met with relief, Gourley said, by all the countries except Russia, which supported the Trump administration. And Russia will be assuming a new role, as the chair of the council, starting in 2021.

That chairmanship probably will lean more heavily toward issues of security and oil and gas, said Gourley.

“Under Russia, it will probably be similar to the years under Trump,” said Sheard. “But it is the Arctic Council, and all of the positive cooperation will go on as well. The studies, the research, the cooperation on emerging issues like plastic debris — all of this will continue.”