Dec. 17 is a historic day on the minds of many people in Tunisia, elsewhere in North Africa and the Middle East — and around the world. That’s because exactly 10 years ago, a single event in Tunisia triggered a series of historic revolutions across the region.

A street vendor selling fruit was fed up with the system. In an act of protest that later inspired millions, he lit himself on fire.

After Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation, the Arab uprisings began in several countries that had only known one ruler for decades. People began to rise up and demand change.

Protests spread to countries that had never seen anything like this, from Tunisia and Egypt to Syria, Libya and Yemen. People poured into the streets, shouting words that became slogans of their hopes and dreams.

Millions chanted phrases in Arabic such as “the people want the downfall of the regime” and “step down, step down, Hosni Mubarak,” referring to the Egyptian dictator. Citizens were tired of having minimal political freedom and sought to exercise their voices. Seeking dignity and human rights, the protesters were also motivated by economic malaise, weak job prospects, demographic pressures and climate stressors.

Related: A poem penned during Libya’s 2011 uprising continues to inspire hope

In some cases, the words of protesters did topple dictators. In others, demonstrations led to greater repression, civil wars and the mass displacement of millions. Islamist parties won several elections across the region, while Sunni radicals began to surge on the battlefield.

What began as a series of idealistic revolutions turned into dashed dreams of democracy and a revival of authoritarian governance in many countries. The decade since has seen yet more instability and violent oppression.

The uprisings that kicked off in December 2010 transformed the entire region forever, and they continue to impact the globe. Here are some key dates in that pivotal first year:

Dec. 17, 2010: Bouazizi sets himself on fire

The Tunisian street vendor from Sidi Bouzid took his own life at the age of 26. Later, he was among five people awarded the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought in 2011 for contributing to historic changes in the Arab world. And the Tunisian government then put him on a postage stamp.

Jan. 14, 2011: Tunisian President Ben Ali resigns

Just a decade ago, the uprising in Tunisia opened the way for a wave of popular revolts against authoritarian rulers across the Middle East known as the Arab Spring. For a brief window of time, as leaders fell, it seemed the move toward greater democracy was irreversible — just as Eastern Europe had felt when the Iron Curtain fell at the end of the Communist Era. Instead, the region saw its most destructive decade of the modern epoch. The resignation of Zine Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia after 23 years in power set in motion similar power transitions in other Arab countries.

Jan. 25, 2011: Mass protests held at Cairo’s Tahrir Square

Tahrir Square, also known as Martyr Square, was the focal point of demonstrations during Egypt’s Arab Spring protests. Located in downtown Cairo, the place is generally hectic and overwhelmed with traffic, street sellers and some tourists. But during the revolution, it was jam-packed with Egyptians calling for a representative government and an end to dictatorship by Hosni Mubarak.

Feb. 11, 2011: Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak steps down

After 18 days of massive protests that rocked Egypt, Hosni Mubarak resigned as the country’s president. The career officer in the Egyptian air force had ruled with an iron fist since 1981, when he became president after Anwar Sadat’s assassination. He later died Feb. 25, 2020, at the age of 91, receiving a military burial at a cemetery in suburban Cairo.

Feb 2011: ‘Days of rage’ explode across the region

Inspired by events in Tunisia and Egypt from the months of December and January, “days of rage” took off around the region, including in Bahrain, where protesters from the majority Shia population rallied for a government more attuned to their interests.

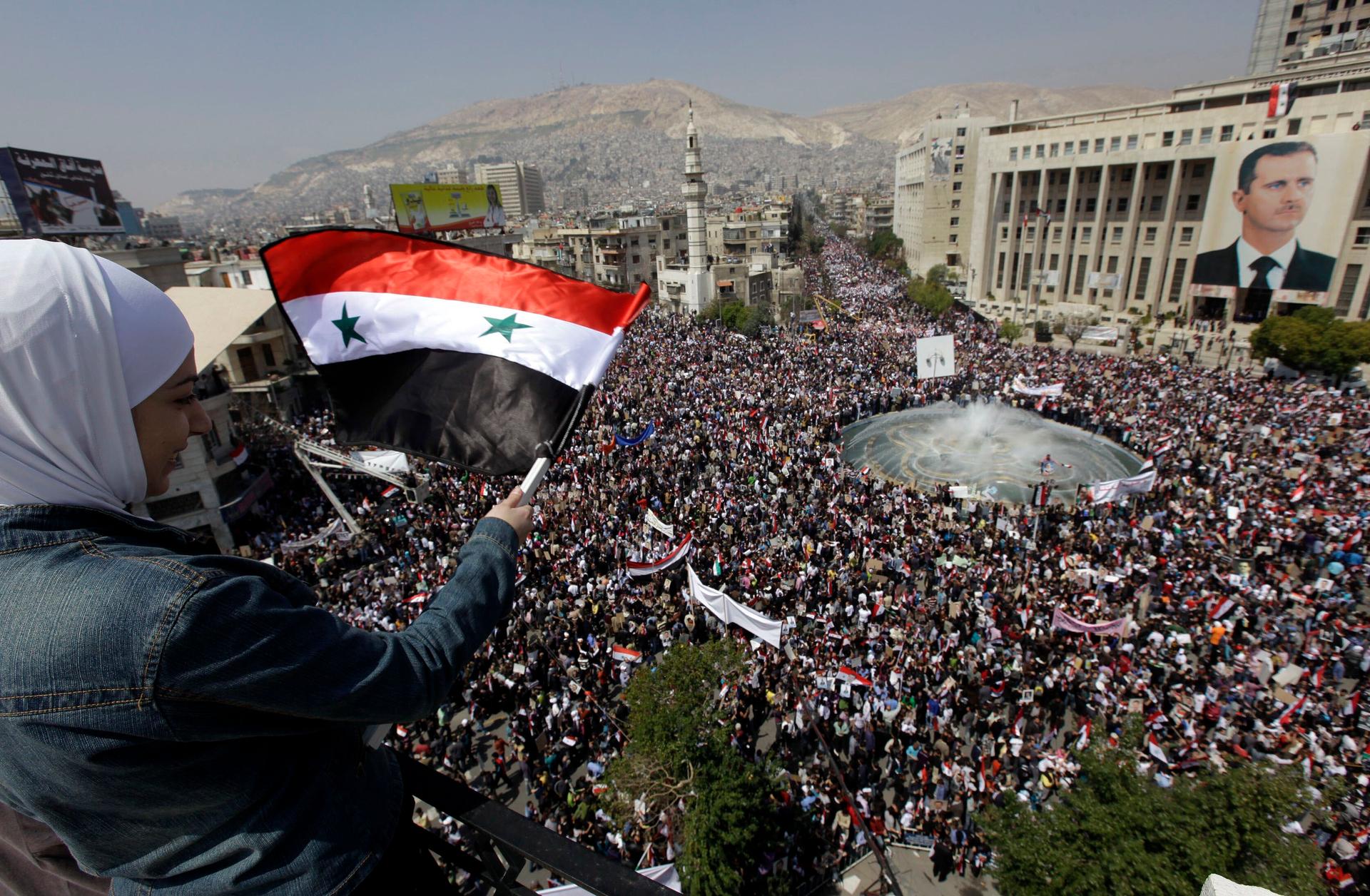

March 15, 2011: Pro-democracy protests take root in Syria

Around 200 young demonstrators gathered in the Syrian capital, as a day of rage called for people to rise up against President Bashar al-Assad’s government. Though the initial gathering was small, the spark was a sign that more was to come in a country where anti-government protest was almost non-existent. However, Assad still garnered much support, especially from minority groups such as the Alawi and Christian populations, in addition to many Druze and Kurds — and even some Sunni Muslims, who formed the backbone of the pro-democracy protesters.

Aug. 20, 2011: Libyan rebels launch battle to control Tripoli

In Syria, the civil war began in March as rebels resisted crackdowns by government forces on protesters. And in Libya, nonviolent protests quickly escalated into violent strife starting in February, with a wide range of factions picking up arms against their longtime strongman, Moammar Gaddafi.

Sept. 23, 2011: Yemenis hold Million Man March

Yemen’s revolution followed the other Arab Spring protests and began to snowball with a mass rally in Sanaa, the capital, on Jan. 27, 2011. Security forces began taking a harder line against protesters in March. Then a transitional council struggled to transfer power to a caretaker government.

Oct. 20, 2011: Gaddafi is captured, tortured and killed

Known as Colonel Gaddafi, the leader of the Libyan Arab Republic reigned from 1969 until 2011. After the situation in Libya disintegrated into civil war, as NATO intervened on the side of opposition forces fighting against Gaddafi. He was seized and killed by militants in a shocking indication of how much Libya — and the region — had changed in just a few months.

Oct. 23, 2011: Tunisia holds first democratic parliamentary elections

Following the Tunisian revolution, an election for constituent assembly was held Oct. 23, 2011, as voters picked the 217 parliamentary members. The vote was considered Tunisia’s first free election since independence in 1956 and the Arab world’s first since the Arab Spring.

Nov. 23, 2011: Ali Abdullah Saleh signs power-sharing agreement

In Nov. 2011, Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh was ready to sign an agreement to transfer power to his vice president, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. But the attempt at a political resolution did not save Yemen from spiraling violence. The country joined the ranks of Syria, Libya and Iraq, which for years have been torn apart by wars, displacement and humanitarian crises.

Nov. 28, 2011: Egypt holds first democratic elections for parliament

Egyptians began voting in November 2011 and continued with a complex parliamentary election through January 2012. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces had dissolved Egypt’s parliament following the ouster of Mubarak. Mohamed Morsi, an Islamist from the Freedom and Justice Party, rose to power by June 2012 but was subsequently removed in July 2013, as the military carried out a coup backed by the opposition and some religious figures. Since 2014, Egypt has been ruled by authoritarian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.