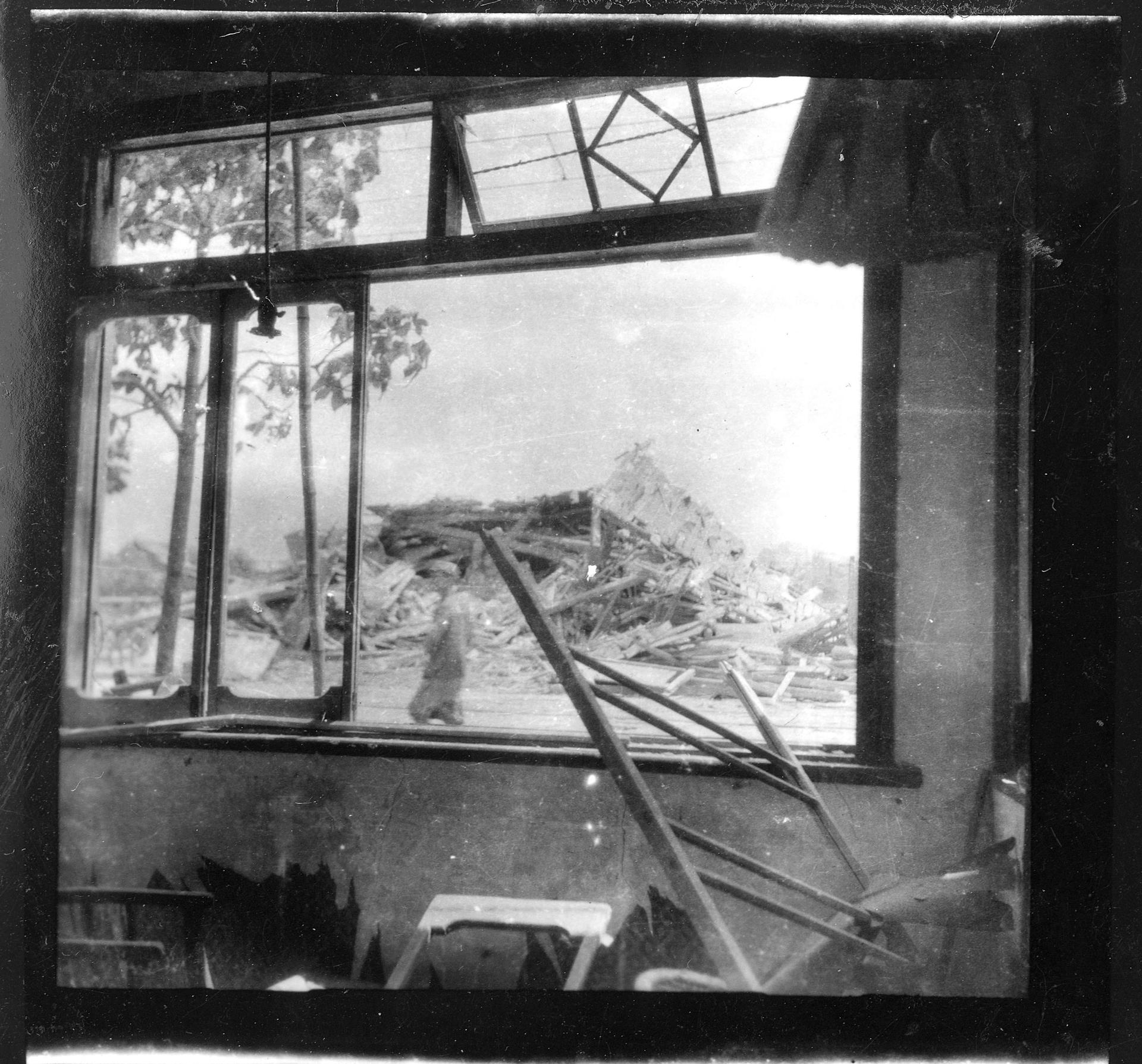

On the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, a photographer roamed through the rubble of Hiroshima, Japan. His images were the only ones known to have been taken that day of people who had been exposed to the atomic blast.

Nearly half a century later, Yoshito Matsushige told his story to Max McCoy, a reporter visiting Japan from Kansas. McCoy speaks with The World’s host Marco Werman about the photographer who captured the devastation across the city on film that day.

Marco Werman: Can you set the scene for us that day, when Yoshito Matsushige took his camera out?

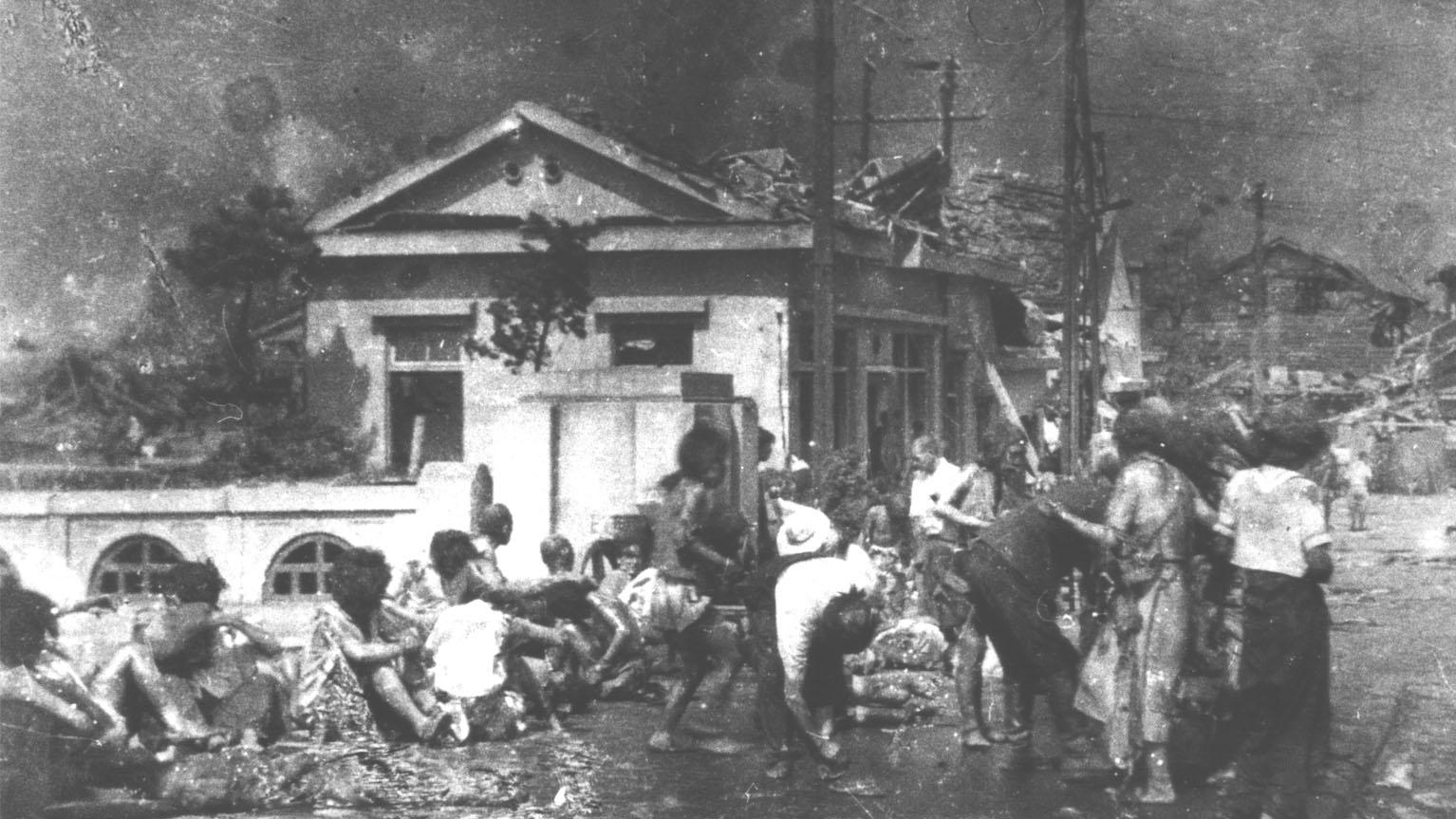

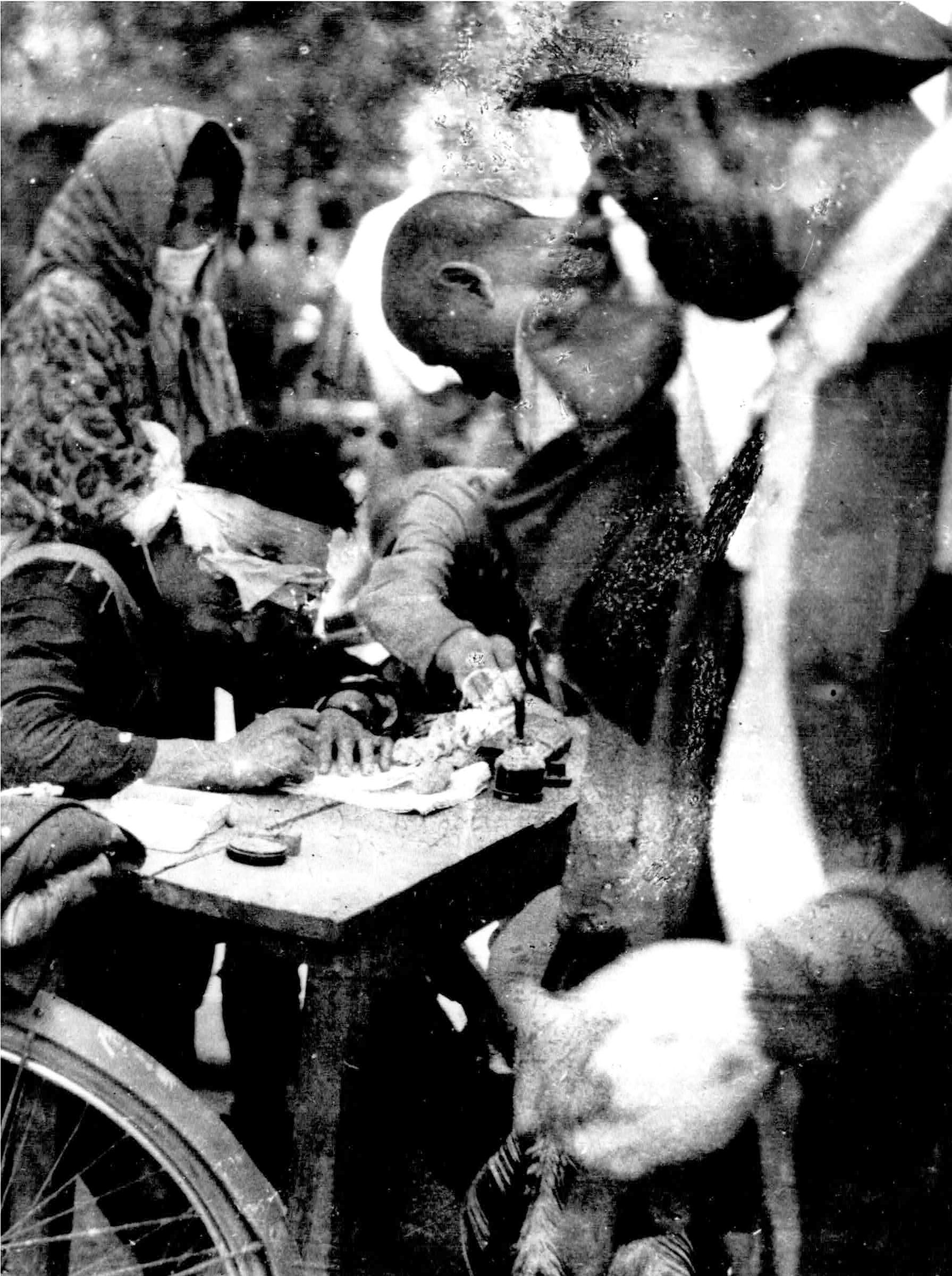

Max McCoy: [Yoshito Matsushige] didn’t take any photographs for quite a while. He could not bring himself to do it. Finally, he did take some photographs at a place called the Miyuki Bridge. And at this location, there was a policeman at a table writing out relief certificates for rice for the survivors. The policeman was heavily bandaged. There was a group of junior high school students clustered on the bridge seeking relief. The only thing that the police could think to do for them was to put cooking oil on their wounds. His most reproduced photographs were on the bridge. And looking at them, you might think that the junior high school students — that their clothes are in tatters and hanging down. But what you’re really seeing is their skin, that the bomb flayed them and their skin is hanging down. And so it’s quite moving and quite horrifying. And after Matsushige finished the photographs on the bridge — and it took him several minutes on the bridge to work up the courage to trip the shutter — he could not take anymore and he just went home.

It is so horrifying and speaks of the immeasurable destruction of nuclear weapons. So you knew the Matsushige story when you went to Hiroshima in 1986. What was it like to be in that city meeting Matsushige face-to-face?

Well, I did have a powerful sense of history. I knew the story. I knew that he had taken the only photographs on the ground. And I wanted to walk with him into the city, the route that he traced. And so I did, along with an interpreter, who was explaining what he was saying, and I was taking photographs at the same time.

What did he tell you on that walk about his own memories of that day, beyond the photos?

He told me that he was confused about what had happened, that it was beyond belief. This is a phrase that was repeated to me by the survivors. He said that he remembered passing swimming pools that were choked with bodies, people sought water after the bomb, and they ended up dying in swimming pools or ponds or jumping into the river. I recall that he told me about streetcars that were packed with corpses and he could not bring himself to take photographs there.

There are so many scenes that he was just unable to photograph, as well. I mean, that he couldn’t push the shutter because the site was so pathetic. It says everything. What did you see in him the day that you met him? What did you see in him that suggested how present August 6 was for many decades later? Was he still living it?

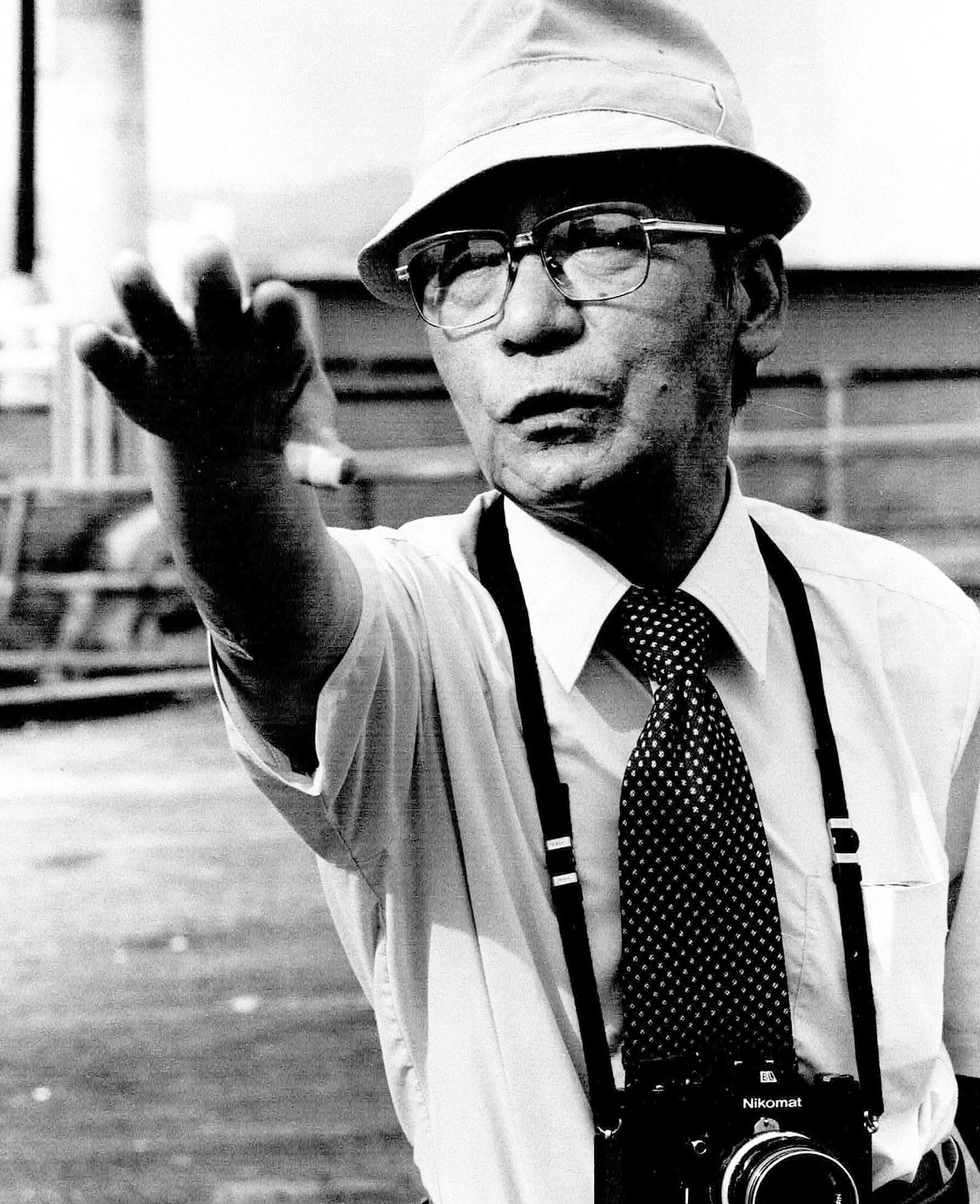

He was when we went to the bridge and he seemed to be seeing those images in his mind. Matsushige was a very reserved individual — snappy dresser, chain smoker, a dedicated newspaper photographer. I recognized a lot of me in him in terms of approach to work, etc. But when we got to the bridge, time seemed to fall away. And what he was describing seemed to be happening before him. And I took one photograph of him in which he’s gesturing and he brought his camera, his modern Nikon with him at the time, but he’s gesturing and you can see it in his face that he has been transported back to 1945.

Max, you’ve written that a photograph is forever a slice of time capturing a testament of the eternal now. So, how are those images from August 6, 1945 — Matsushige’s images — how do they inhabit our minds today and the world we live in right now?

I think you have to make room for them. They seem so alien to us and I believe that you have to be able to recognize how awful we can be to each other. And I’ve heard lots of criticism over the years and people saying, “well, you know, the Japanese brought it on themselves, and this is what they get.” This misses the point. This is not about punishment. This is not about retribution. This is about the survival of humanity. And I think the testimony of those who were on the ground when the bomb was dropped is properly the way we should view it. And I also felt badly for Matsushige, because he was, I think, forever remembering these moments. And I think he thought he failed.

In what way?

Well, he was ashamed of having taken the photographs, a sense of shame about revealing his neighbors in such a distressed state. On the other hand, he also felt that he didn’t take enough. He had a full roll of film in his camera and he only took the five. But in the end, of course, he succeeded, because these are the only photographs taken on the ground. This is the glimpse of the first atomic bombing. And they only suggest the horror.

So that’s the power of photographs. What about just meeting Mr. Matsushige? How did that change you and your own understanding of what happened on August 6, or just war generally?

It has stuck with me and it has changed me in ways that I had not expected. The more I think about his personality and his reserve, his calm and how he approached that experience, [it] has taught me to deal with some of the more difficult challenges in journalism. I should say, Matsushige was transformed. After the bombing, he made a specialty of photographing children in the peace park in Hiroshima. And so, he made a conscious effort to, in his word[s], to say this is why it’s important. This is why photographs are important. This is what we should concentrate on. Since that time, I have become resigned, that you will never change some people’s minds about this, but also more convinced that it is important to try.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Sign up for our daily newsletter