A Black radio host calls on South Asian Americans to reject racism

Exasperation drenched radio host Khafre Jay’s voice as he spoke between tunes on a recent edition of his Sunday afternoon hip hop show. His visits to see family in Sunnyvale, a Bay Area suburb with a large and fast-growing South Asian population, infuriated him.

“People walk past me like they’re afraid,” said Jay, who is Black. “Sometimes people cross the street and then when they get past me, then they cross back.”

But worse, he said, were the times when “people [called] the police on me,” assuming he was up to no good.

Asians make up almost half of Sunnyvale’s population, while Blacks comprise less than 2%. The mistreatment Jay experienced came from Indian Americans, he said.

“There are so many brown people here in Sunnyvale, I don’t know why I should be experiencing racism down here… like, we should be walking hand-in-hand. We face the same white supremacy on a daily basis.”

“There are so many brown people here in Sunnyvale, I don’t know why I should be experiencing racism down here…like, we should be walking hand-in-hand. We face the same white supremacy on a daily basis,” Jay said.

Jay, who is the executive director of the nonprofit Hip Hop For Change, decided to speak out about it.

During one July radio show, broadcast across the Bay Area on public radio station KPOO, Jay went on a bilingual offensive, throwing out Hindi lines he learned on Google to express his frustration.

“Why are you staring at me?” Jay attempted in Hindi. “Do you know that I’m a human being?”

His radio rant came a few weeks into the nation’s deep reckoning with systemic racism in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, a Black man killed by a white police officer in Minneapolis.

“The most beautiful thing about what’s happening after George Floyd is so many white folks out in the streets fighting for Black liberation,” he said.

Indian Americans, too, have come out to protest racism. Within days of Floyd’s death, South Asians in Palo Alto organized a racial justice solidarity protest by spreading the word on Facebook. Yet in protests from Oakland to San Francisco, the South Asian community has not been a large or organized presence.

Related: How Indian Americans are reacting to Kamala Harris as Joe Biden’s VP pick

What Indian Americans often don’t talk about is exactly what Jay called out on the radio: the prevalence of anti-Black attitudes in the South Asian community. This is perhaps one reason more Indian Americans have not joined the protests.

“There is a problem, and we need to address that in the South Asian community,” said Basab Pradhan, who runs a Bay Area theater company that stages plays for the Indian community.

Part of the problem among Indians in this part of California is a lack of exposure to Black Americans within their own communities, says Pradhan, a Bay Area resident of many years.

“There are places in the Bay Area, like Fremont, like Sunnyvale, like Cupertino, where the density of Indians is so high that you just glom onto that instead of widening your social circle,” Pradhan said.

Furthermore, many Indians in the Bay Area work in the tech sector, and Silicon Valley companies employ low rates of Black people.

Pradhan says Indian Americans in the Bay Area tend to have higher incomes and may believe issues like police brutality just don’t affect them.

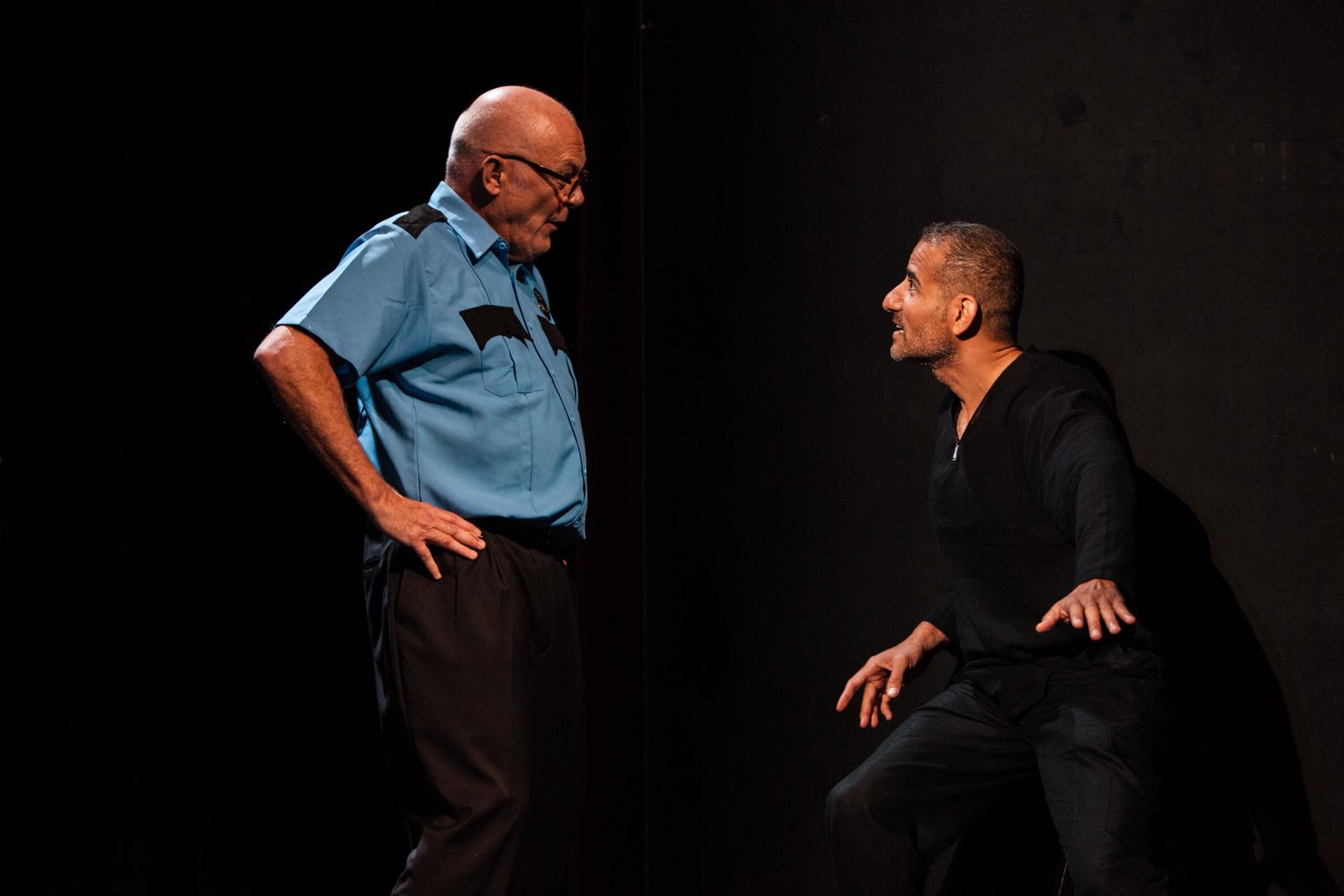

In 2017, his theater company staged a play about police brutality that provoked intense questions about justice and impunity. The play refused to sanitize how African Americans have been brutalized by the police. Yet attendance was low, Pradhan said.

Pradhan’s wife, Vidya, also works to raise consciousness within the Indian community.

“Misinformation thrives in a vacuum,” she said. “If you have no information about the history of Black people, then it’s going to be filled in by whatever comes your way.”

Hollywood’s negative stereotypes of Black men can take hold, Pradhan says. She recently held workshops about Black history for Indian American children. Parents were interested, too, she said, and that gives her hope that this moment of racial justice reckoning might be opening some hearts and minds in the Indian American community.

Yet Basab Pradhan points out anti-Black sentiment among Indian Americans may be connected to something far deeper: India’s entrenched caste system, which traces its roots to a rigid hierarchy present in Hindu scriptures. The priestly class, Brahmins, sit at the top, while Dalits are subjected to the bottom rung.

Related: The US isn’t safe from the trauma of caste bias

Indians of higher castes hold many of the same stereotypes about lower caste Indians that whites hold about Blacks in the US, Pradhan says. Brahmins often believe lower castes to be lazy and not smart, and to get jobs or college placements due to affirmative action programs in India rather than their own smarts. Pradhan says it’s a challenge to erase these beliefs.

“The education system [in India] does not work to blunt caste divisions in India, it works to cover it up. Then you come here and you take that system in your head and you apply it to your new country and it results in prejudice against Black people or Hispanic people.”

“The education system [in India] does not work to blunt caste divisions in India, it works to cover it up,” Pradhan said. “Then you come here and you take that system in your head and you apply it to your new country and it results in prejudice against Black people or Hispanic people.”

Although discriminatory practices by upper-caste Brahmins against lower-caste Dalits are against the law in India, they happen in plain sight.

Caste discrimination also takes place within the Indian community in the US.

A survey by a nonprofit Dalit civil rights group, Equality Labs, found that two-thirds of the respondents felt discriminated against in their workplace due to their caste.

Related: Netflix’s ‘Indian Matchmaking’ stirs conversation about tradition, colorism and caste

In a landmark case brought in June by the state of California, regulators are suing tech firm Cisco Systems, accusing it of discrimination against an Indian American engineer because of his lower-caste status. The company has denied the allegations.

The Cisco case has brought to light more stories from Dalit Indians of caste discrimination at US workplaces. Software engineer Maya Kamble said she has experienced it a lot.

“I never could imagine that I would face the caste system after coming to the US,” she said. “It’s not so easy when you have an Indian manager. Managers have a lot of control over what kind of bonuses you get, whether you get promoted or not.”

Kamble says she recently left a job because of the hostile work environment created by her Indian manager.

Yet, caste discrimination against Dalits is something that has brought lower-caste Indian Americans to identify strongly with other oppressed communities in the US, according to Thenmozhi Soundararajan, executive director of Equality Labs.

“Dalits have been really pushing the rest of the South Asian community that if you want to really show up for Black lives, you have to work on your internal hegemonies of caste and that will really change the way that you show up for all oppressed peoples.”

“Dalits have been really pushing the rest of the South Asian community that if you want to really show up for Black lives, you have to work on your internal hegemonies of caste and that will really change the way that you show up for all oppressed peoples,” she said.

Dalit South Asian Americans have a long history of solidarity with African American communities, Soundararajan said. There were the Dalit Panthers, who were directly inspired by the Black Panthers. And famous Dalit leader, Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, reached across the ocean from India to build solidarity with Black Americans, she said.

“This goes back many years from the correspondence between W.E.B. Dubois and Dr. Ambedkar about the possibilities for engagement at the UN [United Nations] for issues of caste and racial justice,” Soundararajan said.

Khafre Jay, the hip hop community organizer, often invokes the same Black thinkers and activists on his show.

“Part of me is pissed at the [Indian American] community out here for excluding me and making me feel so unwelcome, and using the man and the dogs of the man to police me,” he said.

Yet Jay also wants to express solidarity. And he’s not giving up on learning Hindi.

“As a Black dude looking like me speaking Hindi, I think my biggest point to the Indian community would be like, ‘Hey, we have to fight because oppression for anybody becomes oppression for everybody.’”