A Salvadoran American’s memoir ‘comes full circle’ on a family history of violence, struggle

Writer Roberto Lovato’s new memoir examines his family history between the US and El Salvador, shedding light on the stories behind gang violence and mass migration from Central America.

In his new book, writer Roberto Lovato describes El Salvador as “a tiny country of titanic sorrows.”

And those sorrows, especially in recent decades, have been tightly bound up with lives led thousands of miles to the north of the small Central American country in cities like San Francisco and Washington, DC.

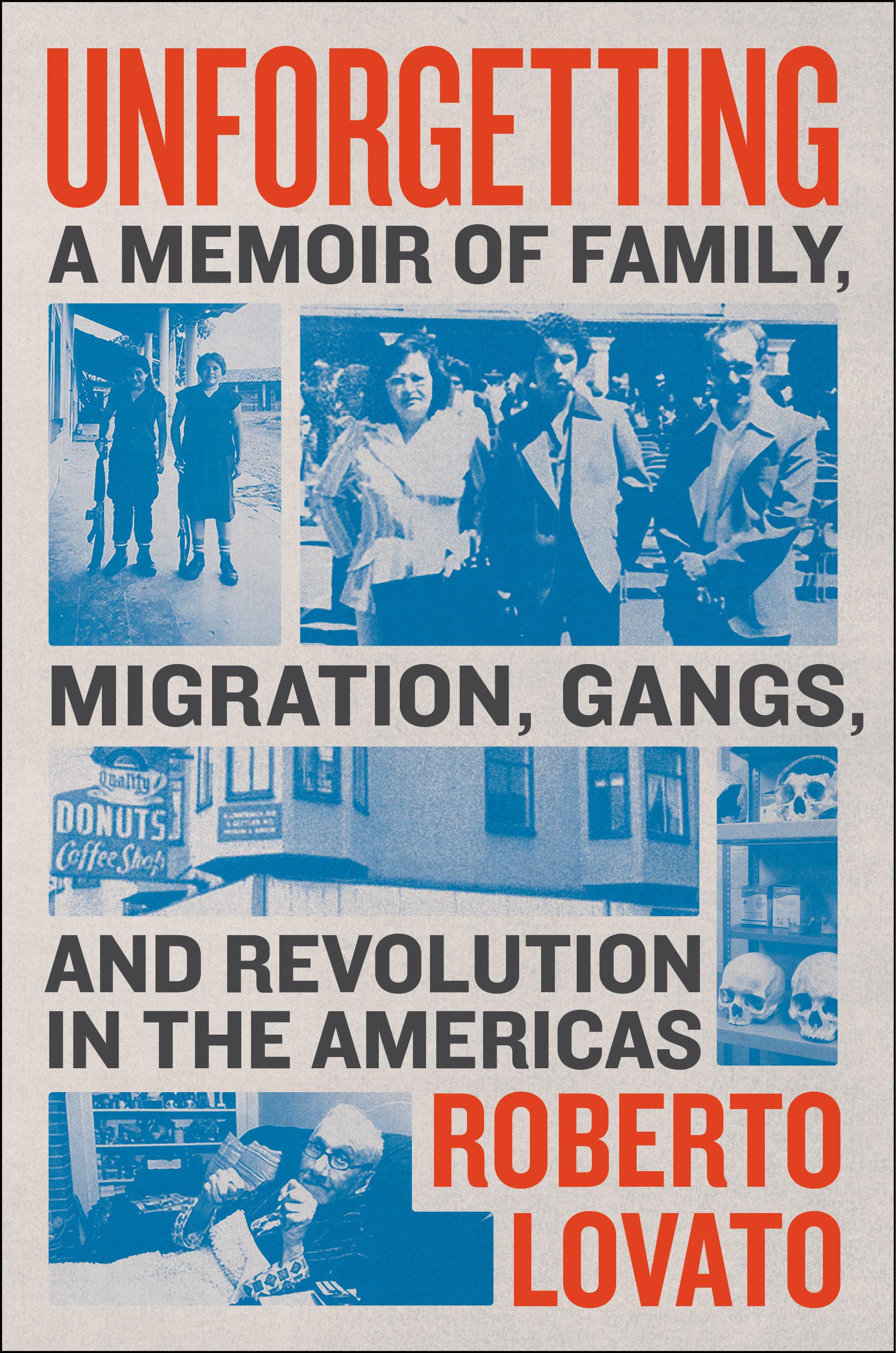

Lovato’s memoir, out today, is called “Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family Migration, Gangs and Revolution in the Americas.” It traces his family’s history between El Salvador and the United States, examining intergenerational trauma and political forces that shape his own family’s story as well as those of tens of thousands of Salvadorans who have fled violence and warfare.

Related: A brother and sister flee gang violence in El Salvador and start over in the US

Lovato is a Salvadoran American former gang member from San Francisco, who went to El Salvador as a young adult to join the guerilla movement in the civil war — and then began covering the brutality of El Salvador’s US-backed military government as a journalist.

He spoke to The World’s host Carol Hills about what he learned about himself, his family, and the connections between the US and El Salvador while writing the book.

Carol Hills: Roberto, this is a fascinating story of your own history and that of the two countries you’re rooted in, El Salvador and the US. You grew up in San Francisco in the 1970s and 80s, the child of Salvadoran immigrants. In your teens, you fall in with a group who call themselves Los Originales. Tell us about that period in your life.

Roberto Lovato: I grew up working-class in San Francisco’s Mission District. We had a little group of us. We weren’t like a formal, hard-core gang. But some of us had low riders and we would do things like steal cars, deal drugs, do drugs or rob people. But we weren’t a hardened gang like you see today in terms of like Crips, Bloods or Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13).

This is all happening just blocks from the infamous Army Street projects in San Francisco. Local news described the neighborhood as “like a prison.” Sounds like a pretty rough place, huh?

You know, as a kid, it was not just a rough place. It was a place where my friends and other people that I knew lived. There was violence and there was crime and everything. But there was also humanity — which tends to be forgotten.

Related: Some Salvadoran migrants look to other nations for refuge as US tightens border

At the same time you were growing up, there was a brutal war going on in El Salvador. Its military was working hand-in-hand with death squads. And President Ronald Reagan was footing the bill and spreading fear about communism encroaching from Central America. What did you and your friends think about that war in El Salvador?

I would travel there pretty frequently because my father was a janitor with United Airlines and my mom was a maid with Hyatt Regency. So, we got discounted hotels and free airline tickets and there were military people everywhere. I was into GI Joe as a kid and Captain America. And I thought, “Wow, there’s some strange things going on.”

Meanwhile, your father — you call him Pop — he’s shipping contraband and guns from San Francisco to El Salvador to anyone who could afford them. You write, “doctors, engineers and military types.” What did you and your family know about what your father did? And how did you make sense of it as a kid?

I was too young to really understand crime and criminality and the way it’s constructed. And so I was initially scared because I heard my dad tell stories about men trying to pick him up and take him away to kill him. And, you know, he would go and find people to sell him guns and other contraband. And then he would take boxes to El Salvador, where he bribed military people and immigration officials would just let him bring the stuff in. And I thought, “Well, man, my dad’s got, like, this transnational operation going on.”

The 1980s was such a heady time in San Francisco’s Mission District. You describe Black power and brown power movements then, and the ripple effects of Latin American liberation struggles. And it’s the music of Mexican American guitarist and songwriter Carlos Santana that provides a soundtrack to this period of your life. For you and your Salvadoran American friends, what was Santana channeling through the Mission District?

At that moment, Santana was channeling the electric currents cruising through San Francisco at the time of the hippies, of Chicano power, of Black power, Cesar Chavez marching down Bryant Street, including the political and revolutionary vibe that started coming here with Chilean and then Nicaraguan revolutionaries who came to San Francisco and established organizations and started being active at coffee shops and protesting in the streets. And eventually, after, like, 1979, a lot of Salvadoran revolutionaries came with them. So, I thought they were kind of scary, intense people at the beginning. Little did I know I would become one of them.

So that’s the backdrop to your teenage years. In your 20s, you head off to wartime El Salvador and work for the rebels. It’s dangerous work. What made you take those kinds of risks?

Being my father’s son, watching my father take risks transferring contraband and doing, like, the outlaw thing, it was not unnatural for me to take risks. And beyond that, I believed in what I was doing when I started realizing that people from the United States were going to El Salvador to either do solidarity work or, Ernest Hemingway or George Orwell, to see these people doing the same thing with El Salvador, which was a movement of its time in the 80s, was, for me, an inspiration.

Related: ICE deported a trans asylum-seeker. She was killed in El Salvador.

All the while, you were researching Salvadoran history, especially the history of “La Matanza” or “The Massacre,” the landmark 1932 uprising when El Salvador’s military dictatorship slaughtered at least 10,000 people, many of them Indigenous. Lots of Salvadorans, including your own family, won’t talk about that horrible event or the fate of the country’s Indigenous. Why not?

La Matanza was, in fact, one of the most singularly violent moments in world history. It’s just an astonishing level of violence that any scholars of, say, the Holocaust or other acts of genocide will tell you that there’s a heavy silence that sets in in a population and in families.

Well, you actually confront your dad about it. You ask him about La Matanza, that massacre in 1932, and he drops what you call an “emotional atom bomb.” Tell us about that conversation.

I never knew why I was such a crazy kid that did the things that I did, whether it was as a youth with Los Originales, or whether joining the FMLN, I just knew that I was kind of crazy. And then my dad told me something that explains a lot, not just of why I was so crazy, but I think it explains a lot of the history of why El Salvador is one of the most consistently violent places on Earth.

And what is that that he tells you?

He tells me that family members had witnessed La Matanza. He tells me things that just move my stomach and move my heart. And really that chapter in my life — it really closed the circle for me as far as my relationship to my father. You know, the arc in my story, like a lot of our stories, is love-my-dad, love-and-hate-my-dad, love-hate-and-then-rebel-against-my-dad-and-the-state, in my case, and then love-my-dad, again.

And so that moment captures that. I go back and forth in time throughout the book so that the reader can hopefully experience a little bit of what I experienced living the life that I lived and not knowing why I lived that life until my father really brings it home for me. I just had to come full circle to my own home to realize that I didn’t have to travel the world to see the astonishing levels of poverty and trauma, that they were baked into my upbringing as a boy and as a young man, and that I didn’t know that I was carrying that atom bomb.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.