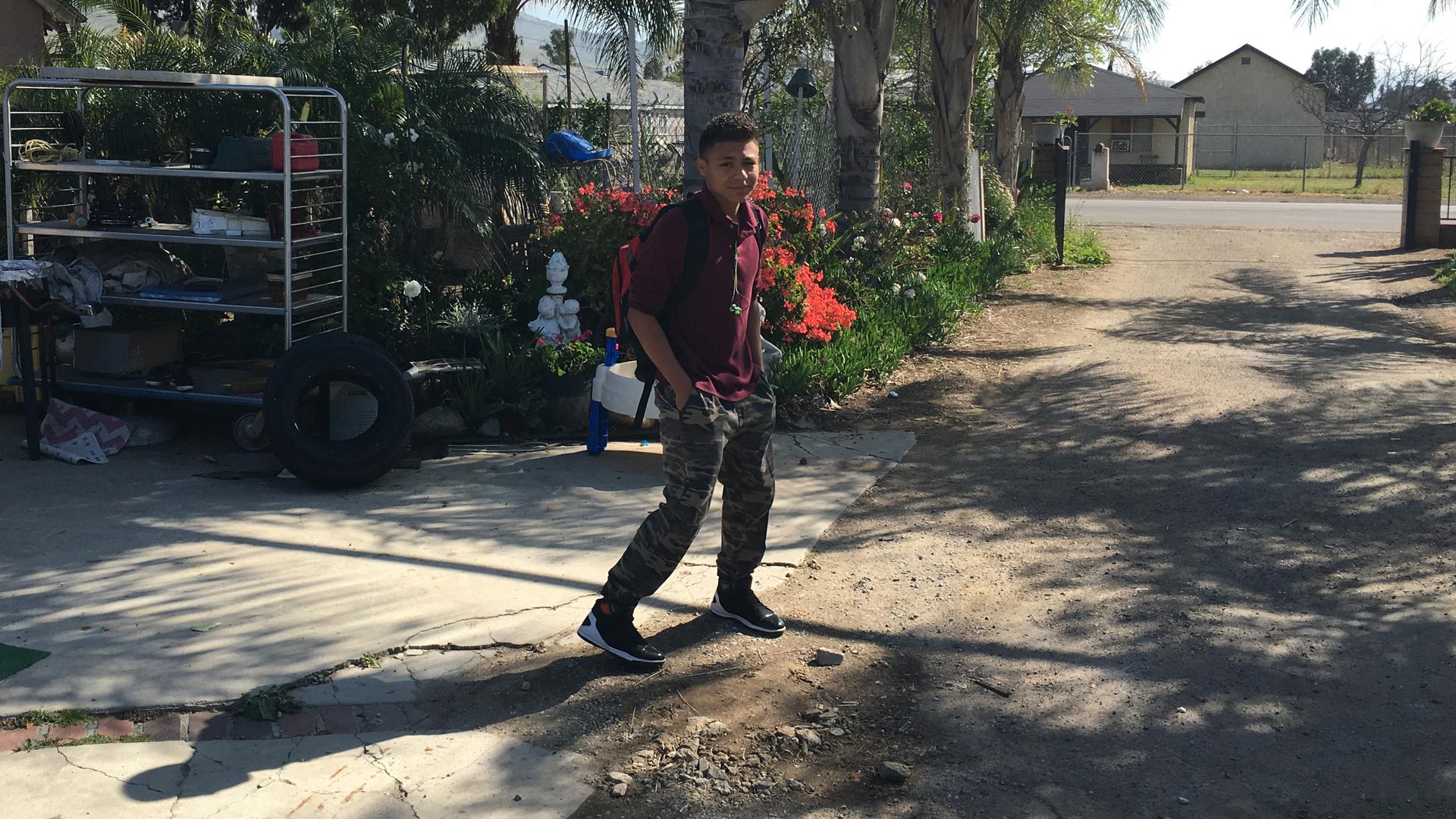

Kevin Alvarez Mejia leaves his house on the way to school in Riverside, California. He fled El Salvador with his sister after being threatened by a gang member.

Kevin Alvarez Mejía spent his tween years trying to avoid running into gang members up in the remote El Salvadoran mountain village where he was born and raised. Gang members lurked around, and if they saw him out on the street, they would sidle up and ask him if he was one of them. So, Kevin said, he stuck to two outings: to school and to church.

But one day they got him.

“It was on the road right below my house where the gang members caught me and beat me up,” Kevin said. “They told me I had a few days to leave the colonia where I lived or they would kill me.”

Kevin, just 13, was scared, he took the threat seriously. He knew he had to get out of there quickly. “I begged my sister to come with me so I wouldn’t have to leave by myself,” Kevin said.

The very next morning Kevin and his sister Sandra, 14, left in a taxi for the Guatemalan border. They had just become two of the unaccompanied Central American minors heading out of trouble and toward the United States.

“At some point we are declared the most violent country on the planet. The next day we are second,” he said referring to El Salvador’s high homicide rate.

Rick Jones, with Catholic Relief Services in San Salvador, said the kinds of death threats youth like Kevin Alvarez received are very real.

“Most of the young people that we see that are leaving are leaving because of threats of violence,” Jones said. His job is to vet cases of people who come to his agency for help, and then, if he believes they are truly in danger, help them find safety. For kids who've been targeted it's hard to hide as the gangs and their networks are spread across the entire country.

“We get people constantly,” Jones said. “Personally I've known of six cases in the last three months of people [saying] ‘I’ve gotta leave and I've gotta leave tomorrow.’”

Crossing through Guatemala and Mexico, Kevin's goal was to make it to California to find his dad. He and Sandra hadn't seen him since he left when they were tiny. They carried a photo with them to help recognize him. In the end, it wasn't that hard to track him down. The siblings were briefly detained in Texas until immigration officials approved their transfer to the custody of their father.

Almost one year later, Kevin is in his final month of eighth grade in Riverside, California. He attends Jurupa Valley Middle School, where he gets personal tutoring and an aide follows him to class to help with translation if he can’t follow. He has a pending asylum case which will determine if he can stay in the US.

Sandra is writing poems in English and Spanish, attends Patriot High School, and cooks dinner for her younger brother after school every day.

Life in Riverside isn’t riddled with threats from gangs, but it also isn’t easy. While the siblings live with their father and his new family, they miss their mom and siblings back home. Kevin misses his mom’s hand-made tortillas. He even misses having to go collect the wood that burns in the outdoor fire on which she cooks the tortillas.

Isabel Mejía, back in the mountain village in El Salvador, also misses her two youngest children a lot. She works six days a week on a coffee estate. The family has a mud brick home with an outdoor shack as the kitchen. There is no running water, a truck comes once a week and the family buys what water they can afford. Mejia says her family is poor.

“All we eat is little beans and tortillas, that’s it,” she said. Sundays, however, are different. In addition to the beans and tortillas, Mejía cooks some rice with carrots, and makes a tomato salsa. Her children and grandchildren are all excited for the Sunday extras.

Isabel Mejia makes tortillas in an outdoor kitchen hut in a Salvadoran mountain village. Her son fled gangs. Tues on @pritheworld. @IWMF pic.twitter.com/7qmlsDY0j7

— Deepa Fernandes (@deepafern) May 9, 2017

There are many mouths to feed in Mejía’s home. She lives with her 79-year-old mother and one of her daughters, Daisy, who has her own child. Another daughter is visiting with her child. Her sons all have kids too.

Daisy said life is hard. “If we want to bathe we have to get up at 5 a.m. and it takes us two hours to get there,” she said. “And we come back all bathed, but then we’re all sweaty too.”

This was Kevin and Sandra's life too, until they left. Mejía said she knew her children had no option but to leave. She worries a lot about them, and she’s often sad.

“I was fat but now I’m really thin,” she said. “Even my children see me and say, ‘oh Mama, you’re so thin.’ ‘Yes,’ I tell them. ‘I miss you a lot, and you know how we live here. Here just about everyone goes hungry.’”

It’s hard to feel the danger that Kevin and his mother felt. This sleepy little village doesn’t seem like gang turf. But Mejía says the dangers are all around.

“Three months ago they assassinated two kids right here,” she said. “It’s really the young ones these gangs in El Salvador are after, like exactly the age of my kids.”

The road leading to her home, curving around the mountain, is deserted. It’s rocky and dusty.

“Kids can’t go to visit another village, the outskirts of our town are dangerous,” Mejía said. “They have to stay home or they’ll be targeted.”

Why don’t parents protect their children from the gangs, I ask her.

“Well, here we can’t protect our children,” Mejía said. “As a mother, a single mother, I can’t protect them against all this violence we have here in El Salvador. I can’t protect them.” All she could do was mandate they stay at home unless they were going to school.

Also: Why would any parent send their kids on the deadly trip to cross the Mexico-US border? Here's why.

While Kevin’s new, and temporary, life in Riverside is clear of dangers, this 14-year-old is often lost in thought. He thinks about his friends back home, his mom. But, he said, he can’t forget the fear he felt.

“I think if I wasn’t here right now, I’d be dead, because they just killed my cousin,” he said. “They went to his house — he lives right near our church — and the gang members were dressed as the police and they took him out of his house and killed him. All because he didn’t want to join.”

Kevin is eating beans, tortillas and an omelet. He sits by himself at the family table and stares vacantly ahead. His cherubic shy smile has disappeared.

“And that would have happened to me if I didn’t leave."

More: Getting an education is the latest battle for migrant children who crossed US border

The reporting for this story was supported by the International Women's Media Foundation as part of its Adelante Latin America Reporting Initiative.