‘The Sirens of Mars’: A scientist’s personal journey and the rich history of Mars exploration

Few people on planet Earth are more deeply involved with missions to search for life elsewhere in the universe than astrobiologist Sarah Stewart Johnson.

Based at Georgetown University, Johnson works closely with NASA on the design, build and operation of robotic systems being sent to Mars to try to discover life, past or present. The newest American interplanetary, robotic life hunter is called Perseverance, which Johnson has helped design. It launched Thursday, July 30, and is capable of detecting and storing the best samples from Mars that have ever been collected.

Over the years, as she worked on this epic quest, Johnson kept a notebook. Now, she has published a book, “Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World,” based on her thoughts and experiences.

“I am just captivated by this idea of, are we alone, and searching for life in the universe, and these big questions: Where did we come from? And why is there something and not nothing?”

“I am just captivated by this idea of, are we alone, and searching for life in the universe, and these big questions,” Johnson says. “Where did we come from? And why is there something and not nothing? Did that something from nothing happen once? Or did it happen time and again? We’re at this moment in human history when we have the tools to answer those questions. … I just feel so driven to try to get to answers to those questions and now we have a way to do that with instruments and with planetary missions.”

Related: Confirmed: More planets are capable of hosting life than have ever been previously substantiated

The history of humanity’s exploration of Mars is long, but not always rewarding. The data collected from NASA’s first flyby of Mars in 1965, for example, was “staggeringly disappointing” to scientists, Johnson says.

The mission’s images revealed that the surface of Mars was covered with ancient craters.

“This meant, number one, Mars had no plate tectonics and, number two, there was no fluid erosion of any sort that would have erased those craters,” Johnson explains. “It meant the surface was ancient and there had been no water there and it was just pockmarked, like the moon. And we just really were not expecting that.”

Fortunately, she says, NASA did not stop exploring. In 1971, Mariner 9, the first mission to go into orbit around Mars, made a number of tremendous discoveries.

“One of them was that the surface of Mars was covered with ancient rivers and that there were all of these features that had to have been created by water,” Johnson explains. “So, even though there was no water today on the surface in liquid form, even though the pressure was too low and the temperature was too cold, Mars was a much different place in the ancient past.”

Later in the 1970s, the Viking orbiters each released a lander onto Mars. These landers did the first life detection experiments on the planet’s surface. The results, Johnson says, were “confounding.”

“The broad conclusion of those experiments was that no life was detected,” she says. “The surface was just very bleak, covered in this red dust that was the consistency of cigarette smoke.”

After a 20-year break, NASA began sending MASH missions to Mars every 26 months, when Earth and Mars align on the same side of the sun. At this point, NASA’s new mantra “follow the water” had kicked into gear, Johnson says.

“Everywhere we looked on Earth, life could be very, very different in different types of environments, but the one constant seemed to be water, at least at some part of its life cycle,” she explains.

The first mobile rover to land on Mars was Pathfinder, which was the size of a suitcase. It landed on Mars on July 4, 1997. ”It was really more of a technological demonstration to show that there was a new type of exploration,” Johnson says. “You didn’t have to just look at what was right in front of your face, you could traverse and you could get to interesting scientific targets.”

The next two rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, landed in early 2004. These rovers, which Johnson worked on with NASA, were about the size of a golf cart. They landed on opposite sides of the planet and were built to last only 90 days. Spirit went on for four years and Opportunity kept going into 2018.

“These missions…have come back with astonishing findings, things that have just brought the planets into technicolor focus,” Johnson says. “Even if the surface may not be hospitable anymore and may not be habitable because of the conditions, down deep in the subsurface, which is one of the most intriguing places to look, I think there’s still a very real possibility that we could find simple microbial life.”

Related: NASA Mars rover finds clear evidence for ancient, long-lived lakes

A lot of Earth’s biomass is beneath the surface in microbial form, Johnson points out and “we’ve barely even scratched the surface” when it comes to this kind of exploration on Mars.

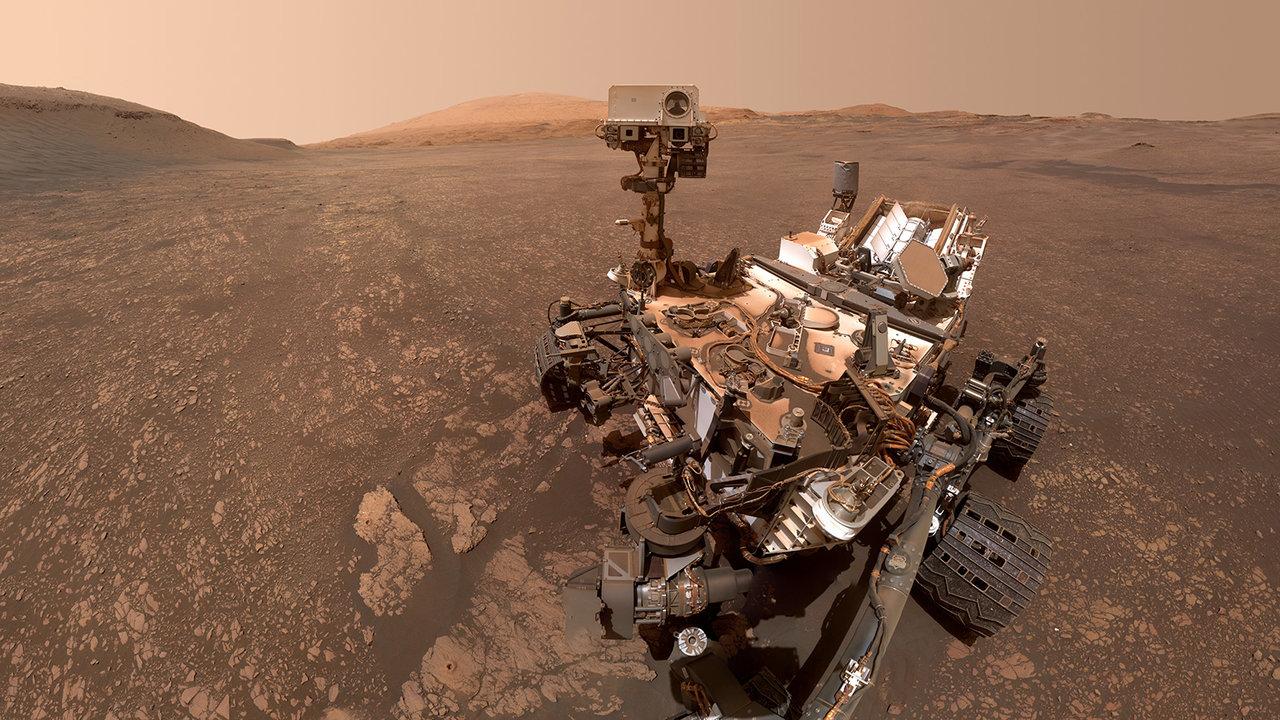

Spirit and Opportunity inspired the idea of sending a scientific laboratory to the surface of Mars. The idea reached fruition with the Curiosity rover, also called the Mars Science Laboratory, which landed in 2012. Curiosity was the size of a car. It landed on the base of Gale Crater, inside of which is Mount Sharp, which rises higher than Mount Rainier.

“Mount Sharp records a very big chunk of Martian climate history,” Johnson says. “We can look at the sediments that have been laid down, like the pages of a history book, and record the environmental conditions. And we’ve been exploring as we’ve been ascending that mountain and we’re still doing that today. It’s been a really exciting campaign.”

“Curiosity has revealed that this is a habitable environment,” Johnson continues. “We’ve moved beyond ‘follow the water’ to understanding that all the ingredients necessary for life, as we know it, are there, or were there in the surface of Mars, and that there was all this ancient water — water that was pH neutral, the kind of water you could drink a glass of had you been standing on the surface billions of years ago.”

Related: Mars Curiosity rover sings ‘Happy Birthday’ to itself (VIDEO)

“We’ve found those organic building blocks of life, those organic molecules have been detected by the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument on the Curiosity rover. And I’ve been fortunate to work as part of that instrument team,” she adds. “So we’ve just done some really astonishing things there with Curiosity. And now it’s time to send Perseverance.”

Perseverance is built on the same chassis but has a different set of instruments that are designed to locate and choose the best samples to collect from Mars. Perseverance is part of a “breathtakingly ambitious campaign to return samples of Mars that are carefully selected to Earth,” Johnson says.

“It’s going to take three missions to do it and a lot of international cooperation, but the idea is that Perseverance will collect a few dozen samples about the size of a penlight, leave them in a cache on the surface, then a fetch rover will come along and pick those up and put them into an ascent vehicle and then another vehicle will come along and collect those out of orbit and bring them back to Earth,” Johnson explains.

Johnson combines her technical expertise and scientific rigor with an unmistakable fascination with the idea of finding life on Mars or on any other planetary target, either here in our solar system or beyond.

“I have to say the thing that excites me most is this idea of a separate genesis, a type of life that’s completely different from anything that we’ve ever seen before,” Johnson says. “And I can tell you this; If we find it on Mars — that’s just the next planet, that’s our near neighbor — it would have huge implications. It would imply that the universe would be positively teeming with life.”

“We’re a small species in this vast universe and our lives are just incredibly short on the scale of geologic time, and we really just have a moment to be here,” Johnson concludes. “And it just makes life so very precious and so very special, and we’ve really just got to make the very most of this one moment that we each have.”

This article is based on an interview by Bobby Bascomb that aired on Living on Earth from PRX.