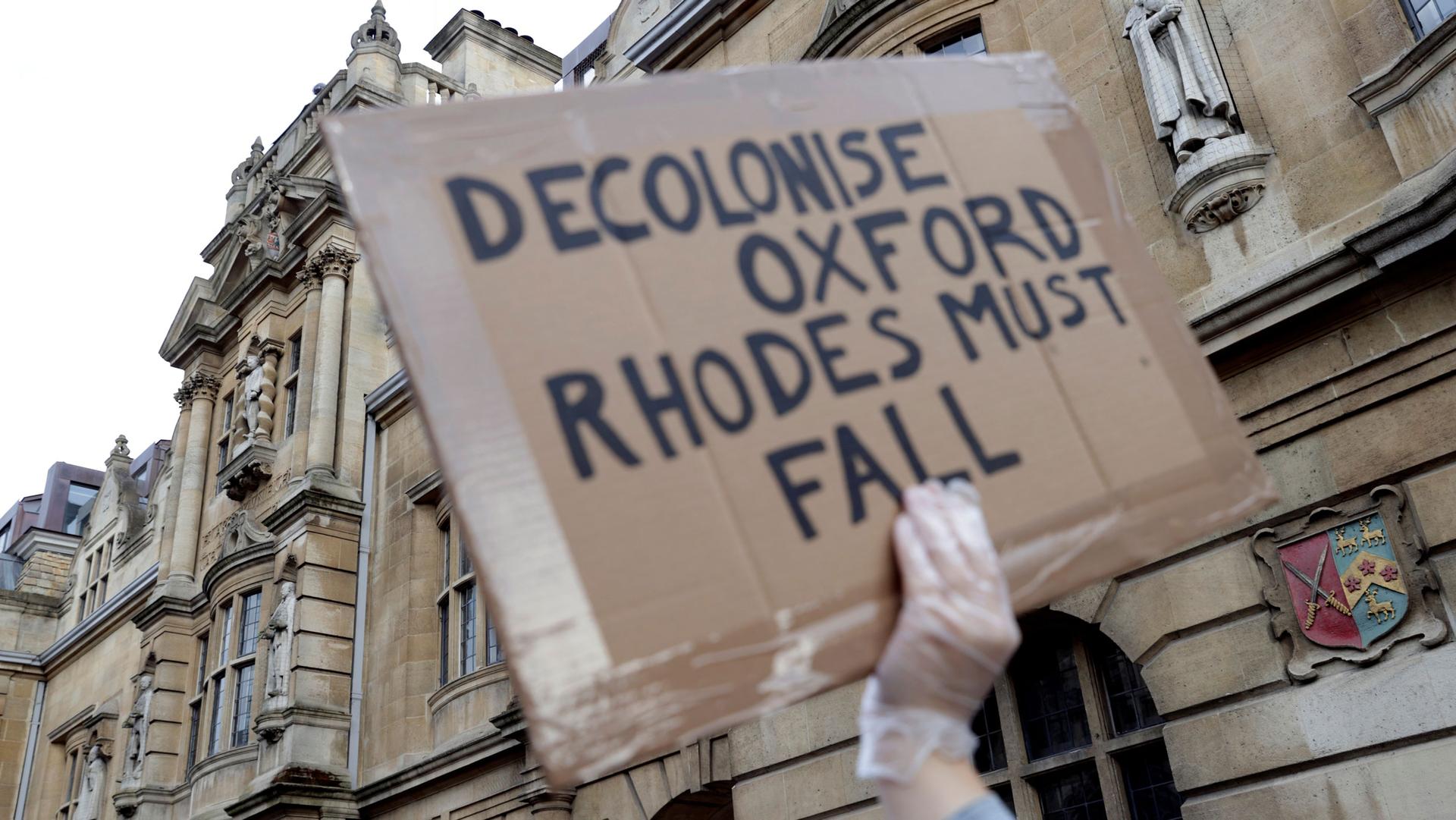

Following the death of George Floyd who died in police custody in Minneapolis, a demonstrator is seen with a placard during a protest for the removal of a statue of British imperialist Cecil Rhodes on the outside of Oriel College in Oxford, Britain, June 9, 2020.

The police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on May 25, confirmed suspicions many Europeans have long held about the depth of racism in America.

But Europe has its own colonial past and racist present. Protests in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States are bringing a reckoning in Europe, as well.

Related: Felling of slave trader statue prompts fresh look at British history

“One of the differences between America and Europe is that when it comes to anti-black racism, Europe’s most egregious acts took place abroad. Our civil rights movement took place abroad, our segregation, our slavery. And so our civil rights leaders — we don’t have a Martin Luther King, but we do — as Britons — have a Gandhi, have a Kwame Nkrumah. Portugal has Amílcar Cabral, and [Joaquim] Chissano [from Mozambique],” said London-based author Gary Younge.

“But the fact of that distance, that arm’s length, means that it hasn’t been internalized in the same way. And so there is this challenge to really teach the history in order to understand the present.”

Younge, also a professor of sociology at Manchester University, spoke with The World’s Marco Werman about the difficult and challenging process for Europeans to come to grips with racism in European society.

“A very prominent activist here, [Ambalavaner] Sivanandan, had a phrase when people would say, you know, ‘go back to where you came from.’ The phrase was ‘But we are here because you were there.’ Now, of course, if you don’t know that you were there and you don’t know what you did there, then it’s very difficult to understand why people are here and how and why they might see history as very different to you.”

Related: In France, Black Lives Matter echoes in the case of Adama Traoré

Marco Werman: So, Gary, you’ve written in the New York Review of Books, “What Black America means to Europe.” One line stood out to me: “From the vantage point of a continent that both resents and covets American power and is in no position to do anything about it, African Americans represent to many Europeans a redemptive force …” Explain that.

Gary Younge: They see in black Americans a way of embracing America — because you’re embracing that bit of America that is least co-opted, least bought into the kind of power structure, least representative of the power. Now, this is, of course, problematic, because if you take George Bush-era where American foreign policy — the bombing of Iraq, Axis of Evil, Guantanamo Bay — American foreign policy was articulated by either by Colin Powell or Condoleezza Rice, the face of American foreign policy was black. And then you get on to [Barack] Obama, who Europeans adored, and he was then the face of American power. … He was the architect of American foreign policy, which didn’t change that much between George Bush and himself. So, it’s not that it’s not problematic, but what they’re trying to do is finding a way to embrace the America with which they have a deeply ambivalent and complicated relationship. They covet its power, they resent its power. They kind of enthrall, by and large, to elements of its culture — some elements of its culture and not others. And here stands this group, which signifies both that America is not all that it claims to be, but that America could be so much more.

Related: America’s BLM protests find solidarity in South Korea

So when you write that African Americans represent to many Europeans a redemptive force, is that sensation having a moment? And do you think it will be permanent?

There are severe peaks and troughs and also moments of dissonance. And I don’t think Brits understood Colin Powell or Condoleezza Rice. There is a kind of infantilizing element to this — they love African Americans so long as they are playing the role that’s expected of them, as opposed to being full human beings. So, it is not unproblematic. America’s standing has never been lower in Europe than it is now. This particular set of rebellions and resistance — George Floyd isn’t just a murder, he’s a metaphor. He’s a metaphor for a lack of democracy, for a kind of race-baiting president who doesn’t care about the rest of the world, doesn’t care about anyone, who’s has a kind of deep-seated xenophobia himself. This lands in a moment where people see a huge need for redemption. This notion of a redemptive force takes an outsized position.

Related: Concerns of structural racism ‘deeply existential,’ UN expert says

Gary, you live in London. Your parents were from the Caribbean. You experience race as a black man. I know you’ve said that you hear frequently from Europeans that when it comes to racism, it is, “better here” in Europe than in the US, suggesting degrees of racism. How do you react when you hear that?

When people say that to me, I say, well, there is no good form of racism, there is no better form of racism. I lived in America for 12 years. My wife is African American. When I came back to Britain, people said, “Well, that must be because the racism so bad.” I said, “Do you honestly think I would come back to London to escape racism?” And there is this kind of competition almost, this desire for moral superiority — having rescinded material superiority and military superiority and economic superiority to America, there would be some moral superiority, and that in some way we should be happy with the racism that we have.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.