In Moldova, poverty and corruption go hand in hand.

In 2016, a single act of bank fraud by a group of politicians known as the “theft of the century” led to $1 billion siphoned out of the country into offshore accounts — that’s 12% of the nation’s gross domestic product. The country’s average household income over the past 10 years is just over $14,000 a year, causing a third of the nation’s workforce to leave and seek work abroad.

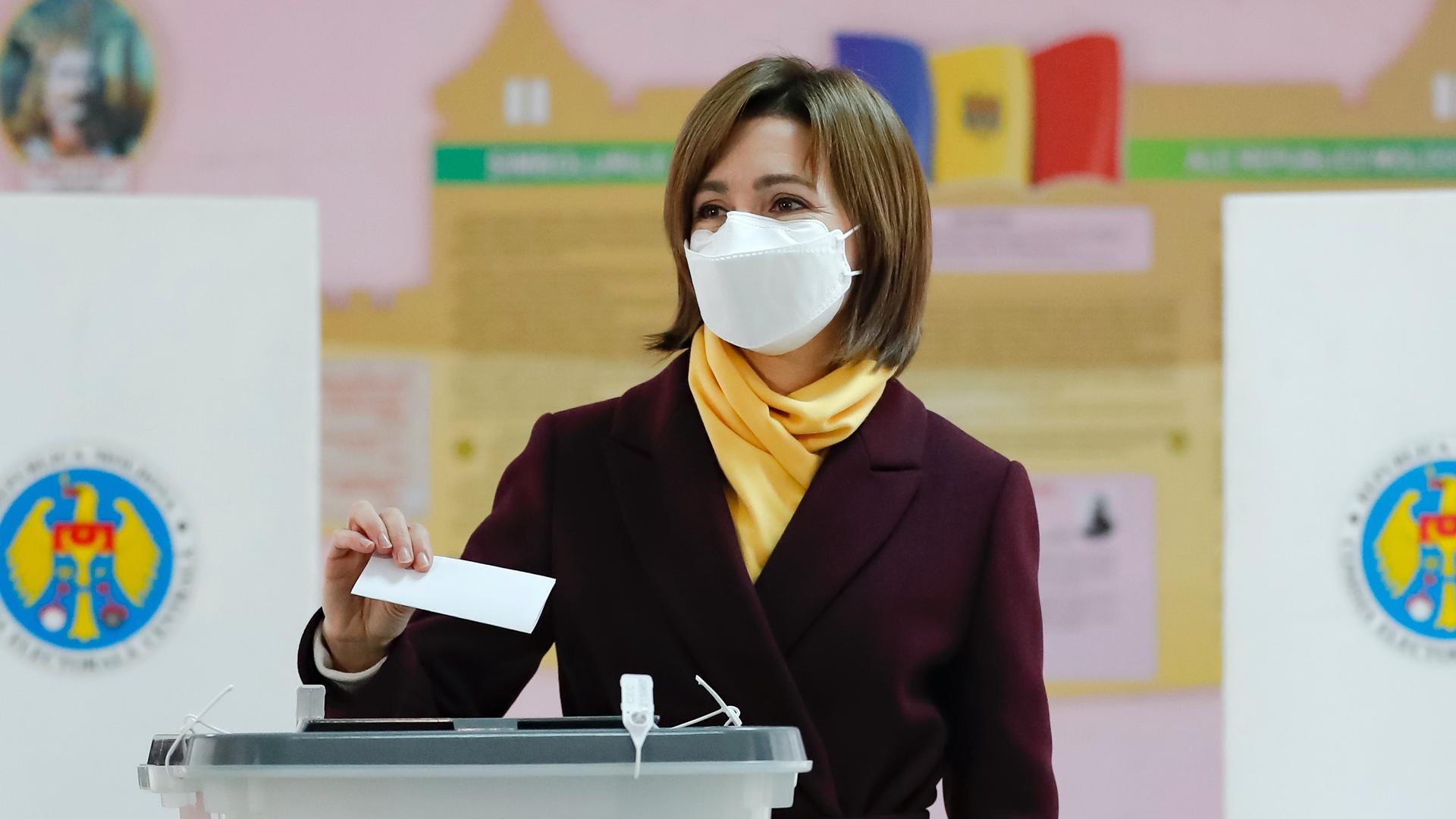

So when Maia Sandu, the recently elected first woman president, ran a campaign focused solely on addressing corruption, 93% of Moldovans abroad voted for her, bringing in 244,000 votes and lifting her above the incumbent, Igor Dodon, who lost by a thin margin of 27,000 votes. Diaspora voters comprise 15% of the Moldovan electorate.

Related: Anti-government protests swell in Bulgaria amid corruption allegations

Sabina Costin, a Moldovan who now lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota, said she’s not someone who cares about politics, but Sandu stood out as a promising candidate because she prioritized cleaning up internal corruption and strengthening ties to the European Union.

Costin, who is 29 years old, became part of the Moldovan diaspora at age 17, when her family won the US green card lottery and moved to Minneapolis.

One of the first things that stood out to her when she started working in the US was that bribery wasn’t common practice in institutions. Costin remembers the corruption her family had to endure to get her into a good charter school when she was in second grade in Moldova.

Related: Trump’s hypocrisy on corruption is just what Putin wants

When she didn’t fully pass the entrance exam, her mother and she both dressed nicely, went to the school and asked the authorities, “How much do you need to get her [into] the school?” Costin says they wrote down a number on a piece of paper to indicate the amount. Her mother negotiated, and she got in.

Costin said her experience is normal in Moldova, where a 2015 survey showed that one in five Moldovans had paid a bribe to public officials in the 12 months leading up to the survey.

“The further we go with more transparency, we will be able to achieve so much more, in my opinion.”

She believes that the only way to bring Moldovans back home is by cleaning up the widespread government corruption. “The further we go with more transparency, we will be able to achieve so much more, in my opinion.”

“The fact that Russia has restrained itself from intervening actively in these elections has been very good news for the entire region.”

“He has promised that Putin would visit Moldova, which has not happened in the last four years.” Joja added, “The fact that Russia has restrained itself from intervening actively in these elections has been very good news for the entire region.”

Joja said Dodon’s strategy, promising Moldovans that a strong relationship with Russia was in their future, failed with Moldovans abroad who valued Sandu’s anti-corruption platform and promise to oust corrupt government officials. “They see how well they fare in the West and they want to be able to do as well at home and to be able to return home.”

Related: Ukraine is ‘sending a very clear message to corrupt elites’

Joja said that Moldovans working abroad make up the biggest foreign investors to the country’s economy: “In 2019, 16% of Moldova’s GDP [came] from the diaspora through foreign remittances.”

Moldovans abroad see Sandu as a hero for having left Moldova only to return and make a life for herself, Joja added. Sandu left Moldova to pursue an education at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government but returned home to take a job at the Ministry of Education in 2012.

When The World asked why she returned, Sandu said, “Because Moldova is a beautiful country with very nice people.”

In her time as minister, Sandu said she “reduced the number of bribes in the education system by half” — an accomplishment she believes demonstrates her capacity to deliver on her promise to tackle corruption.

“These are young people, a creative working-age population [who] can contribute a lot to Moldova. And they left because they didn’t have any prospects at home. They still believe in their country. They want things to change in our country.”

Sandu said she empathizes with the diaspora. “These are young people, a creative working-age population [who] can contribute a lot to Moldova. And they left because they didn’t have any prospects at home. They still believe in their country. They want things to change in our country. And as a proof to that is their participation in the latest presidential elections a few days ago,” she said.

Related: Lebanon protests called out corruption. Now it’s about survival.

Moldova does not have mail-in voting, meaning Moldovans abroad had to find international polling places. Some of them traveled hundreds of miles to vote. “People had to stay in lines for two, four, seven hours,” said Sandu, who also said high voter turnout among the diaspora shows that Moldovans abroad hope to “create a functional government to have the rule of law for the people to believe in their country.”

As for her plans on tackling corruption, Sandu said, “Unfortunately, some of the existing judges are corrupt, some of the people who are already in the system are corrupt.”

During her first week in office, she said she will be proposing a law “to clean up the system [and] do the evaluation of judges and prosecutors. She plans to use every possible opportunity — including the National Council for Security — to make sure that state institutions focus on high-profile corruption cases.

Sandu said that she knows fighting corruption is dangerous work. Her own mother worries for Sandu’s safety. But now that she has won the election, Sandu said her mother rests a little easier knowing that her daughter is supported in her efforts. Sandu said this support gives her the courage to help create a new Moldova — a Moldova that people can come home to.

Natalia Cucoș, an excited Sandu supporter based in Austria, said she hopes someday she can return to her motherland. “You can take the person out of Moldova, but you can’t take Moldova out of the person,” she said.