Scientists across the world are racing to develop and test vaccines to combat the novel coronavirus.

There are currently no approved treatments or vaccines specifically for COVID-19. No vaccine is expected to be ready for use until at least 2021, as any potential vaccine must be widely tested in humans before being administered to hundreds of millions, if not billions, of people.

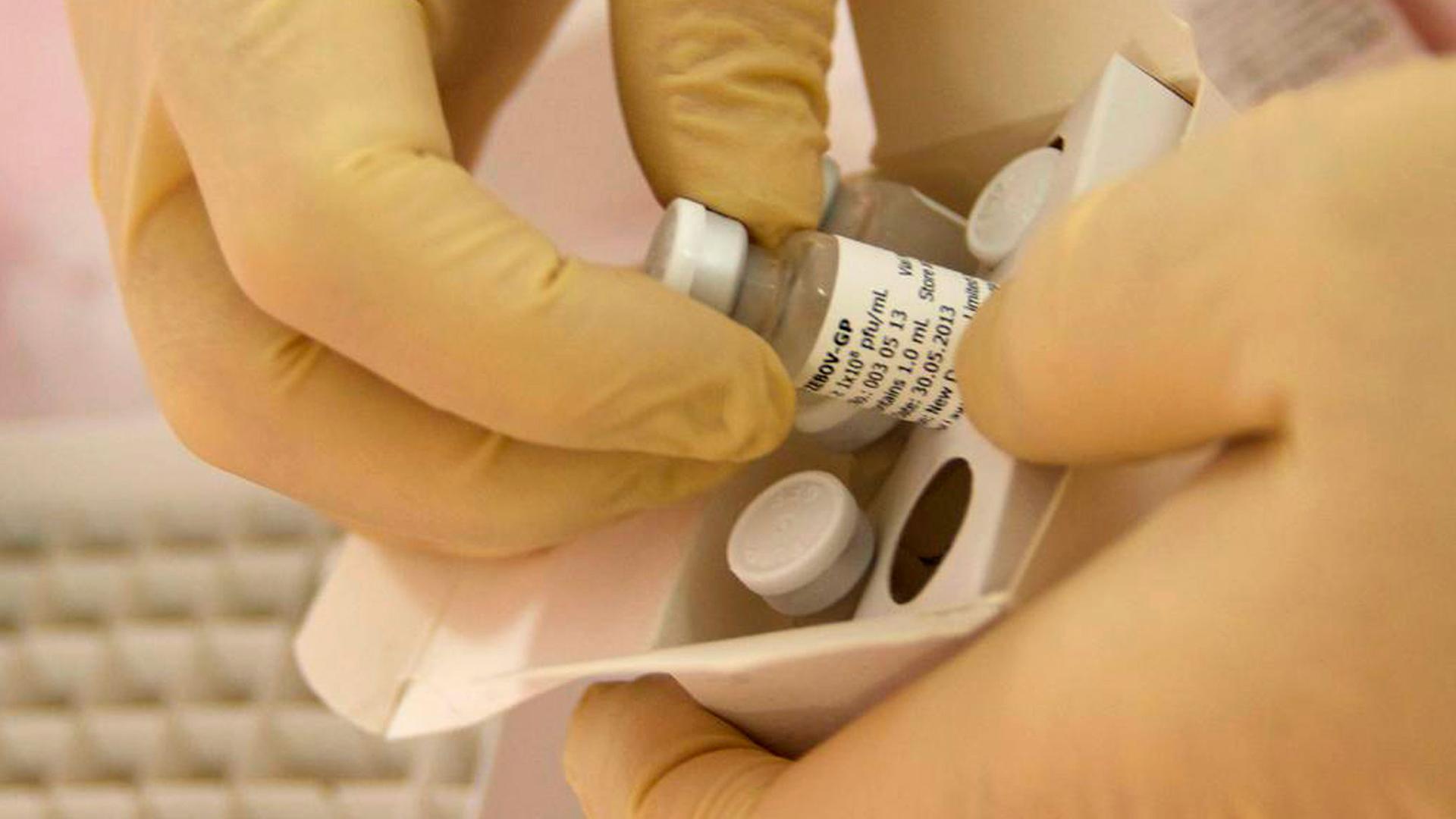

But researchers are collaborating at unprecedented levels, says Gary Kobinger, director of the Infectious Disease Research Center at Laval University in Quebec, Canada. Kobinger was a key scientist leading the creation of an Ebola vaccine and has successfully worked to fight other epidemics, including the Zika virus. He spoke The World’s Marco Werman about progress in developing a vaccine for COVID-19.

Related: International researchers race to develop a COVID-19 vaccine

Marco Werman: Gary, where are you at in the process of developing a vaccine that would tackle the coronavirus?

Gary Kobinger: Well, we’re contributing to different vaccines, different initiatives with the belief that, for us, if we can support as many as possible, we can evaluate as many as possible so that at the end of the day, we have the best vaccine making it through phase one, two, three. Then we can select hopefully for more than one possible vaccine that will show the best potency and safety profile.

And vaccines, let’s remember, are not a cure. Just remind us quickly what the point of a vaccine is.

That’s correct, yes. So a vaccine is really to prevent disease — or at least to lessen the burden of a disease. So it’s really a preventive measure. Instead, a treatment is really an intervention that is given when somebody is already sick, is already infected, [for] minimizing the symptoms, the severity of the disease and even the length of the disease itself.

Related: Scientists say Ebola is no longer incurable

So it seems like you’ve got some first good steps. When did you start your work?

We were made aware of the emergence of the virus on the 1st of January, as a matter of fact, within 24 hours of China reporting the information to the WHO. There are a lot of those alerts worldwide every month, as a matter of fact. Thankfully, most of them are not leading to major pandemics like we are seeing right now. But we started really talking more specifically about the vaccine and other intervention two weeks later in mid-January.

We really started working actively with people full-time on it towards the end of the month. With all due respect, it’s been a short time, but we have made tremendous progress as a community. You’ve seen clinical trials started already in the US. There’s a second one that started yesterday that we are part of, as well as the vaccine that is advanced by Inovio. And we are also supporting two other vaccines — both of which, actually, we’re hoping to see entering already clinical studies — phase one clinical trials — in June.

Gary, you pioneered vaccines and treatments for Ebola, for Zika, other diseases as well. What do you see as different about this coronavirus? What strikes you about it?

What strikes me in this virus is that we are lucky — we have a vulnerable population, but we have a large population that are mainly resistant to severe disease and death. I’m talking about those less than 10 years old. Overall, the young individuals are less likely to develop severe disease. That’s still a reality today. It doesn’t mean that they are completely immune and they’re completely protected. Absolutely not. Some of the young individuals, unfortunately, are going through severe disease, and we can see some fatalities, as well, in this group. So it’s for them to also take this very seriously, [like] everybody.

Related: Massive vaccine campaign underway in Philippines after polio’s return

How confident are you a vaccine will work 100%? I mean, there are these reports from China of people who have recovered again, testing positive.

Yes. And we are following those very closely. But for now, they are a minority and it seems — again, we’re waiting for more data on this so I don’t want to speculate — but it seems from early reporting that the very small minority that come back with the second wave of disease, the disease seems to be milder. Vaccines are never 100%.

We have to understand that we as a population are very diverse genetically. And some people react better than others to vaccination, meaning that they get better protection. But, you know, if we reach 80%, we’re already very happy. …If we get 70% protection in [the] population, it’s enough to severely slow the spread of a pathogen.

Is a vaccine the only approach? What about other therapies? How is science doing on that front?

It’s just one approach, and the more we have, the better. So treatment is very important, and it’s important to save those people that are in severe disease, that are NICU, that are going to die. So intervention directly on people that are positive [for the disease] is extremely important. We see a lot of work being done on different molecules — on the use of plasma from convalescence and monoclonal antibodies. They’re all very, very critical interventions.

But, you know, also what’s being in place now — physical distancing, washing hands — all these are measures that also minimize. You can see them a little bit as a buffer of a vaccination, as some sort of a shield — you’re trying to shield people and to protect them from exposure.

Related: Taiwan’s success in fighting COVID-19 is overshadowed by global politics

I’m just curious, Gary, to your thoughts on the reaction of the world to this pandemic in terms of trust in what you’re doing — developing a vaccine — as well as mistrust, because the world invest a lot of hope in what you’re doing. But you’ve also experienced deep mistrust as you develop vaccines, right?

Yeah, and it’s quite interesting. [There’s a] back and forth between, you know, the trust that is there — please go fast, fast, fast, we need a vaccine, we need a vaccine. And at the same time — yeah, but what if this vaccine makes it worse? What if this vaccine causes side effects? What if these interventions make it worse or cause side effects? This is why it’s important to really fast-track everything, but not skip any step, especially on the safety level.

Right now what’s, I think, unique is the level of global collaboration, at least at the [scientific] level. Actually, there’s so many conference calls, there’s not enough hours in a day to follow everything that is happening. But it’s to tell you there is a lot of collaborative approaches now. It’s not about my vaccine, your vaccine. This is why we’re also, on our side, trying to help as many as possible. It’s not about our vaccine. We have one in-house … but it’s it’s not as a big priority because we are not as equipped as others and we prefer to make others benefit from what we can do to fast track their vaccine rather than ours. So this is what you’re seeing now and it’s what happened with Ebola. I think this is why we managed to see a vaccine — two vaccines — going through phase three clinical trials in 18 months. And it was quite unique.

That collaboration is encouraging, I’ve got to say. So let me make it about me. When will I be able to get a vaccine for the coronavirus, likely, do you think?

Yeah, I wish I could tell you. I wish I could know myself. And the reality why I don’t know and I cannot tell you is because it’s not my decision. It’s nobody’s decision in terms of vaccine developers. It’s regulators — they have the final say as to when clinical studies start, when vaccines are appropriate to roll out at the population level.

But I can say this: In relation to a lot of other vaccine efforts, this is going extremely fast. We’ve never seen several vaccines entering clinical trials within three months from the emergence of a pathogen. This has never happened before, that I know of. So I think this is very encouraging to see. …So people are getting more optimistic, believing that they can make things happen faster. So I think it’s very promising on that side. But it needs to be done the right way. It needs to be done the safe way, so that when we have a vaccine, it’s protecting people, not doing the opposite.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.