As tourists flock to Barcelona, locals fight to preserve their neighborhoods

A tourist leaps in the air with a backdrop of the skyline of Barcelona, Spain, on Aug. 3, 2017.

In the main dining room of a 19th-century building on the outskirts of Barcelona, Spain, a few dozen people watch two women play the guitar and sing. The panoramic views from the sunroom are breathtaking — the art nouveau glass panels let visitors look out over the city. Beyond, the Mediterranean Sea glistens.

Eulalia Castellò gives a tour of the building called Casa Buenos Aires. She shows the sunroom, which was designed by a famous Catalan architect, and its immense backyard full of pine trees. Since March, more than a dozen activists have been taking turns living there, protesting a private company’s plans to demolish the building and put up a luxury hotel.

Related: Squatters occupy Venice homes in housing protest as tourism surges

The Vallvidrera neighborhood is far from the city center where tourists flock. There aren’t any hotels here — at least not yet. But the location is close to the famous Tibidabo amusement park, a second-tier attraction, and as Barcelona gets more and more saturated with visitors, the tourism industry is beginning to spill over into residential neighborhoods. In 2018, more than 15 million people visited the Spanish city and spent around $14 billion.

“We decided to occupy as a protest and a political statement,” said Castellò, the designated spokesperson for the group of activists.

She said they want this building to continue serving the local community, as it has for more than a hundred years. After it first opened as a hotel in 1886, complete with a loft for carrier pigeons used to reserve rooms, Casa Buenos Aires served many functions, including a university dorm and a hospital during the 1930s Spanish Civil War.

But the place has been empty since 2011 when a retirement home run by a Catholic entity closed. The property owners want to sell to a hotel developer and have initiated a judicial process to kick the squatters out.

Related: Puerto Rico’s new land-use zoning map strikes a nerve with fed-up citizens

Castellò, a social worker, said squatting was their last resort. In 2017, a group of neighbors tried to buy Casa Buenos Aires for around $2.7 million with the idea of converting it into a community center. But the offer was rejected because it wasn’t enough money.

“We don’t want people to be driven out of their neighborhoods,” said Castellò. “Because it’s in these neighborhoods where we take advantage of local commerce, where people build a community.”

If a luxury hotel goes up, she said, local shops will start catering to tourists instead. Hardware stores will close, and expensive restaurants will open up, which can drive up rents.

The building’s owners turned away multiple interview requests. And the company that wants to demolish the building hasn’t officially made the purchase, so it said it wouldn’t comment.

“The building has been a source of good for the neighborhood,” said 78-year-old María Rosa Montolio, who has lived down the street from Casa Buenos Aires since the 1960s.

Walking up the hilly street carrying several bags of groceries, she said she spent many years attending events at Casa Buenos Aires or strolling through its gardens, which were open to the public. But she thinks turning the place into a luxury hotel “will only bring more complications.”

“It’s important to fight for the neighborhood,” said Montolio. “I don’t support the illegal squatting of a building, but I’d rather have the protesters there than tourists.”

Janet Sanz, Barcelona’s deputy mayor for ecology, urban planning and mobility, said Barcelona needs more affordable housing, not more hotels.

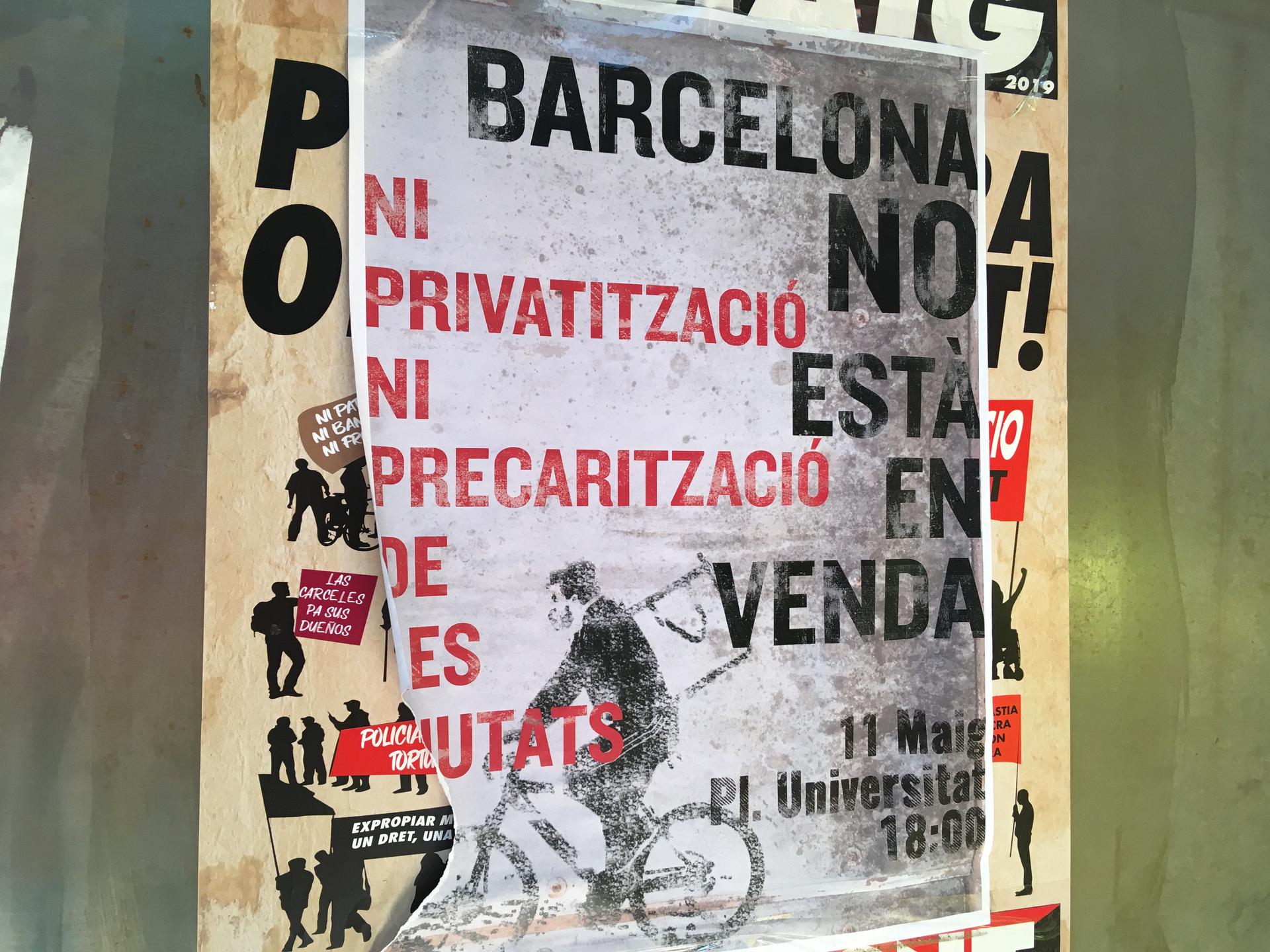

“There’s a strong response from the community that’s saying: ‘Enough. Enough’,” she said.

The current administration — led by Barcelona’s Mayor Ada Colau, a former housing activist — has limited the number of hotel licenses in some areas and has stopped handing out Airbnb licenses altogether. Still, the city’s economy relies heavily on vacation dollars and euros coming in, and Sanz recognized this. But she said that, while the city benefits from its international appeal, it’s important to keep the tourism market under control — and prioritize residents.

“If private companies, the community, and the local government work together, we can figure out what’s best for Barcelona,” she said.

Related: Puerto Rico’s Vieques island ousted the US Navy. Now the fight’s against Airbnb.

Back at Casa Buenos Aires, neighborhood activists like Castellò are less hopeful.

“Casa Buenos Aires is not an isolated case,” she said. “It’s a symptom of a bigger issue happening all over the city. If we organize as a neighborhood, we’ll reach a compromise that serves everyone. And we’ll send the message that the tourism industry can’t do whatever they want, whenever they want.”