Chinese medicine is getting WHO recognition. Some doctors are alarmed.

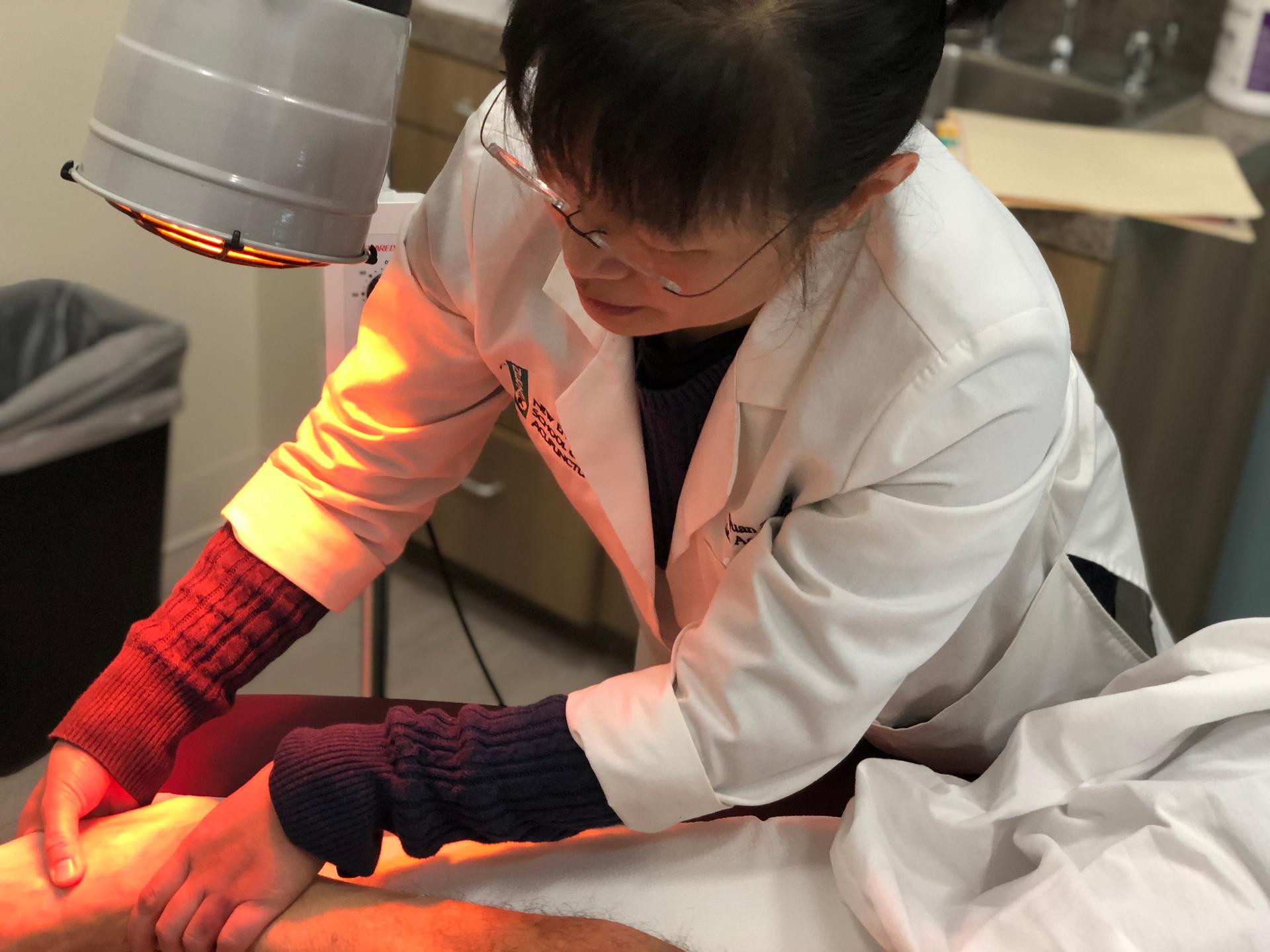

Traditional Chinese medicine, or TCM, is a complex practice that approaches health through the body’s relationship with nature. Practitioners seek to restore that balance through different herbal remedies and therapies like cupping and acupuncture.

Meridian channels and qi, or energy, are having a moment on the global stage.

For the first time, The World Health Organization (WHO) is including a section on traditional Chinese medicine in its upcoming guide for diagnosing and classifying diseases.

Practitioners welcome the update, but in Europe, the move is setting off alarms among top medical and scientific groups.

Related: Is acupuncture a viable alternative to opioids?

“We were quite astonished to see something like that has no scientific support to be included in a document that is so widely used across the world,” said Dan Larhammar, president of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, who help draft a statement published this month by a coalition representing European academies of science and medicine.

Traditional Chinese medicine, or TCM, is a complex practice that approaches health through the body’s relationship with nature.

“The terminology, the language is different,” said Song Xuan Ke, a traditional Chinese medical doctor who has been practicing in London for three decades.

Related: When treating sports injuries, does the West do it best?

Traditional Chinese medicine is rooted in the ancient principle of Yin and Yang. These opposing forces correspond to different parts of the body and have characteristics like hot and cold, calm versus active.

Health problems are a sign of an imbalance, perhaps a kidney Yin deficiency, or blockage of qi in the meridian line, or energy channel, in the body.

Practitioners seek to restore that balance through different herbal remedies and therapies like cupping and acupuncture.

It can be more subjective and individualized, Ke told The World, compared to Western medical approaches.

WHO’s diagnostic manual was created in 1948, and has become an international standard for reporting data on health conditions and causes of death. It has also been revised a lot, as medicine itself evolves. The inclusion of a chapter on TCM in the upcoming edition was approved this spring and takes effect in 2022.

“This shows the world is multidimensional, so this is great,” said Ke, who hopes the move will be a boost for the field around the world.

Related: Why a US health clinic suggests Cambodian treatments for insomnia

That is exactly what the Federation of European Academies of Medicine (FEAM) and the European Academies’ Science Advisory Council (EASAC) — a coalition representing European academies of science and medicine — fear. In November, they issued a statement calling on the European Union to do more “to ensure that all medical products and procedures are subject to an appropriate level of evaluation for quality, safety and efficacy…”

They want to clamp down on claims of unregulated herbal drug treatments and interventions.

“If unproven methods are claimed to be useful then we are risking the health of the patients.”

“If unproven methods are claimed to be useful then we are risking the health of the patients,” Larhammar said, adding that the move could legitimize quack assertions about cure-alls for cancer and other diseases and pressure health systems to incorporate unproven practices, like using an ingredient in animal hides to fight cancer.

“Nobody has been able to define a meridian or acupuncture point. No one can say what diameter an acupuncture point has, or how deep it is in [the] skin, whether point same size over body. It’s still totally unknown — and most likely, [an] explanation for that is they probably don’t exist.”

In a separate, searing editorial, the journal Nature wrote that the WHO risks promoting an unfounded philosophy and is likely to fuel the sale of largely unproven treatments.

In an emailed statement, WHO spokesperson Christian Lindmeier wrote that the inclusion of TCM “is not an endorsement of the scientific validity of any TCM practice or the efficacy of any TCM intervention, but a tool for counting, and comparing TCM conditions. The chapter provides the means for doing research and evaluation to establish efficacy and safety of TCM.”

For Dominik Irnich, a doctor at the University of Munich, and head of a pain center at the hospital there, the European academies’ cautionary warning is a good thing but “a little bit exaggerated.”

“I feel it’s not just about regulation, it’s about acceptance of traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture in the Western world.”

“I feel it’s not just about regulation, it’s about acceptance of traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture in the Western world,” he said.

Irnich is also president of the German Acupuncture Association and active in international groups. He has found that some traditional approaches, like acupuncture for chronic pain, have shown promise in his practice.

“There’s scientific evidence, and for example in Germany, it’s well accepted,” Irnich said. “We have about one-third of German doctors who are very familiar and use it.”

Still, he said it’s best incorporated under the umbrella of Western medicine, where practitioners have backgrounds in both fields and scientific research methods can provide more checks. As it stands, he says policies and regulations surrounding TCM vary from country to country. They often don’t exist.

“There’s a need for a call of regulation,” said Irnich, referring to the level of the European Union. “So this makes sense.”