Colombian farmers combine agriculture, ecology to solve economic, health woes

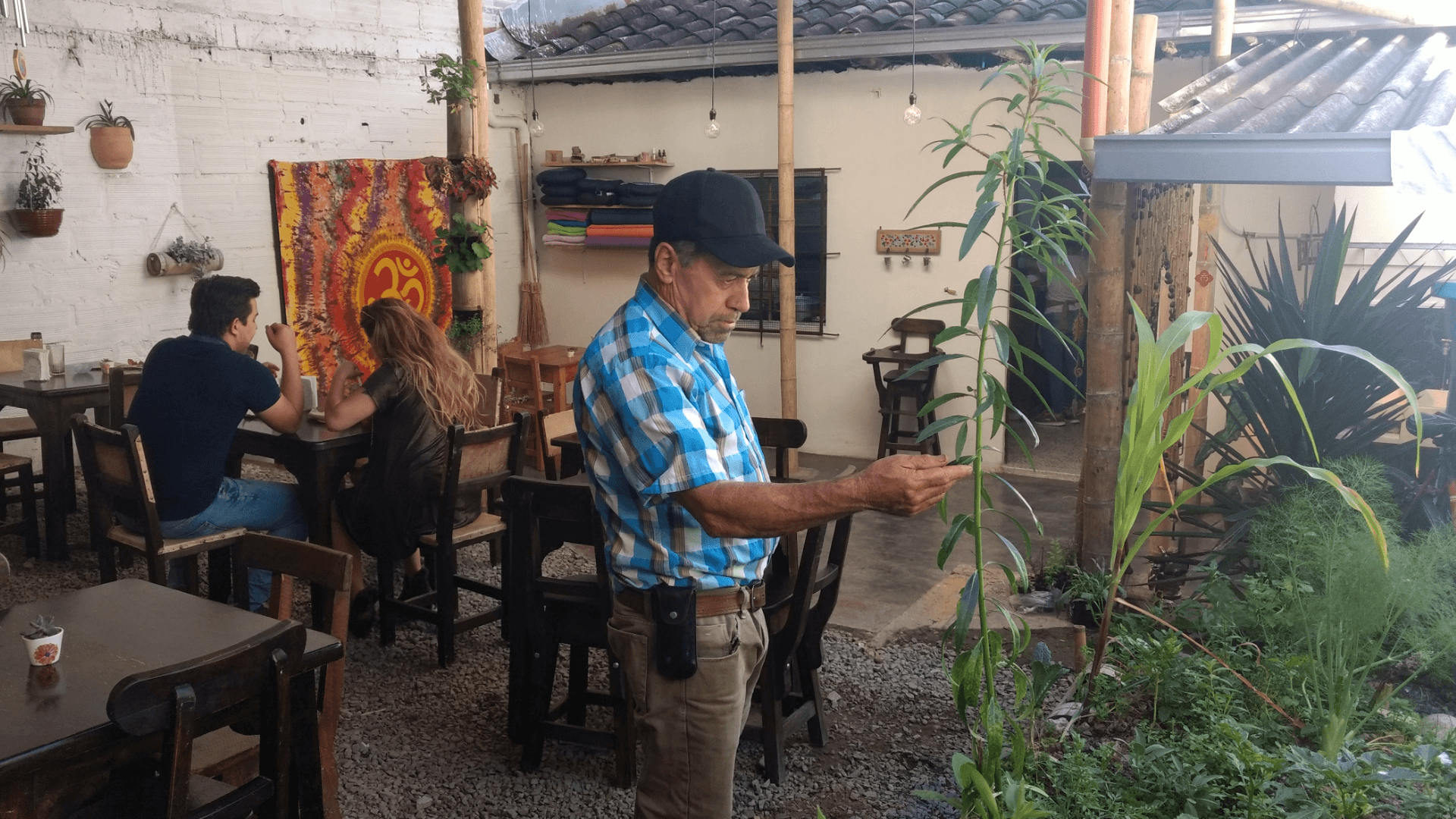

Farmer Carlos Osorio checks up on the kitchen garden at his produce store and restaurant in La Hojarasca, in El Carmen de Viboral, Colombia.

For over 20 years, Carlos Osorio, 65, was a conventional farmer outside the central Colombian village of El Carmen de Viboral — spraying pesticides every single day.

But after falling gravely ill, he decided to abandon all agricultural chemicals and start using sustainable farming methods.

Today, Osorio has an honorary degree in agroecology from the University of California, Berkeley, and uses his farm to train a new generation of local farmers — and bring city-slicker Colombians and foreign visitors to the farm to tell his story and reconnect them to the land.

Related: Without respect for Indigenous rights, climate change will worsen, UN says

In the developed world, concerns around pesticides, herbicides and industrial fertilizers are often framed around their impact on the environment, but for Osorio and many other farmers in Colombia, health concerns are also driving the switch to agroecology, which focuses on incorporating ecological principles into agricultural practices.

According to Colombia’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, there are over 106,000 acres of agroecological farmland with product destined for international export, with an additional 197,000 acres for domestic consumption — as of 2014.

That is dwarfed by the 17.5 million acres cultivated using conventional farming methods.

“I’ve been working on the farm since I was 12. And for most of my adult life, the Colombian government has been promoting the use of these chemicals.”

“I’ve been working on the farm since I was 12,” Osorio said. “And for most of my adult life, the Colombian government has been promoting the use of these chemicals.”

But in 1994, he started to have serious health problems, leading to months of not being able to work full time.

Related: Despite the peace deal, former FARC fighters face a new war in rural Colombia

“I had blurry vision; I had headaches all the time,” he said. “The more I used pesticides — especially in the sun — the worse it got.”

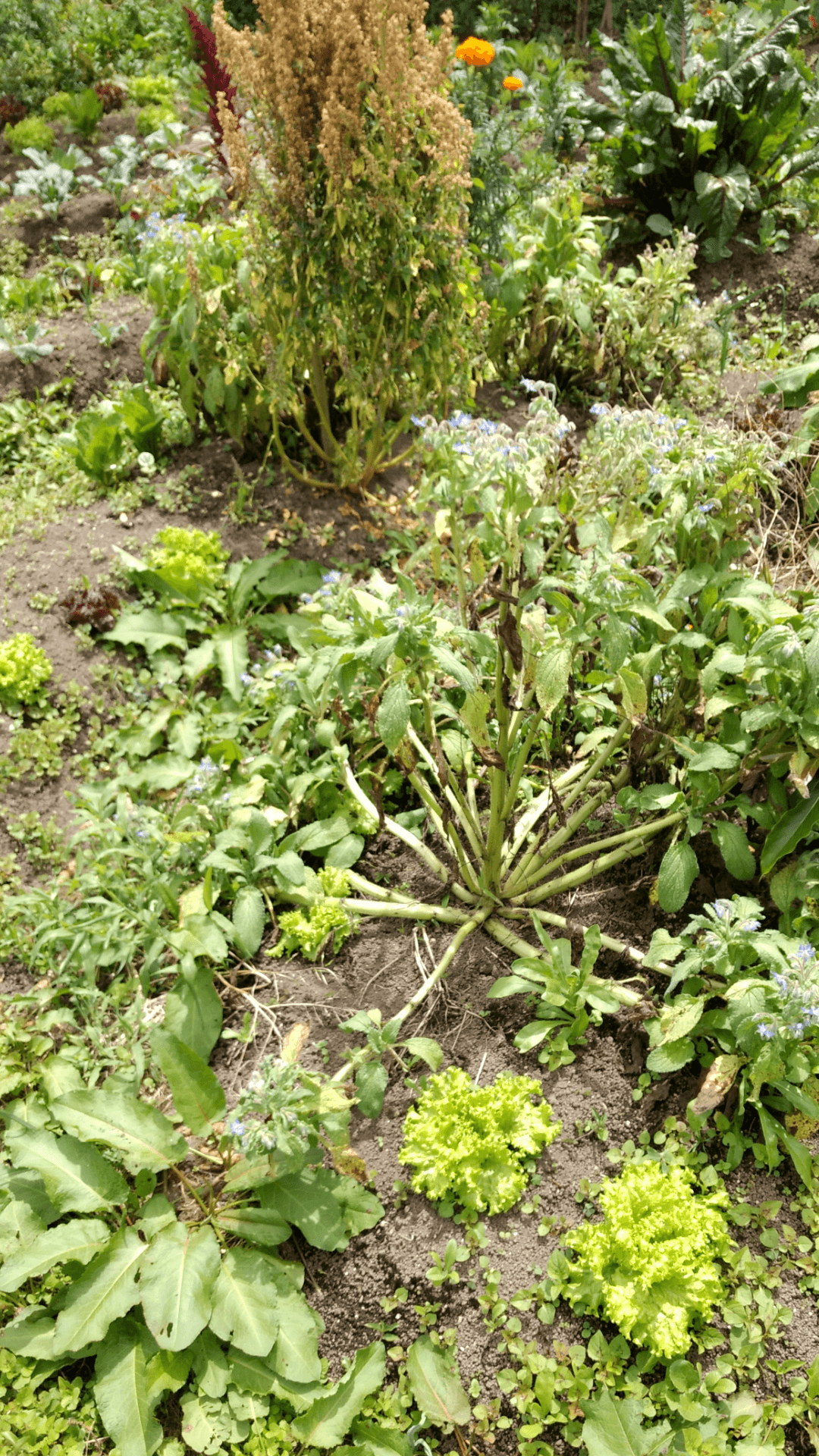

Osorio says that after hearing about agroecological practices from a medical professional, he decided to go cold turkey on agricultural chemicals practically overnight and became a member of a collective of five families who all adopted the same principles. The families used alternative planting methods such as co-planting, differently shaped fields and eliminating the use of industrial chemicals. He says that since making the switch in 1994, his symptoms have faded away.

“One experiment was to make a circular field, and we found that the chillies and soy emerged more quickly, as opposed to growing in rows,” he said.

Rubén Salas, a toxicologist at the University of Cartagena on Colombia’s north coast, says the scientific literature is clear on the effects of organophosphorus pesticides like the ones Osorio used in the past. They produce muscle weakness, neurological damage and long-lasting chronic effects.

“Although they are regulated, you can see that these pesticides are still being widely used because of how many people are still getting sick.”

“Although they are regulated, you can see that these pesticides are still being widely used because of how many people are still getting sick,” he said.

According to statistics from Colombia’s National Institute of Health, 8,423 cases of pesticide-related poisoning was reported nationwide — more than one-fifth of all reported cases of poisoning in the country in 2017. Additionally, all causes of death involving pesticides (including suicide) accounted for 150 fatalities in Colombia in the same year.

Salas says pesticide-linked causes of chronic diseases are unlikely to be detected by general practitioners, and thus, are likely underreported in epidemiological studies.

Related: Coffee farmers struggle to adapt to Colombia’s changing climate

Osorio says despite the alarming health statistics, agricultural methods aimed at lowering chemical use are not yet mainstream — and many farmers aren’t about to change.

“Most farmers aren’t thinking about the effects that agricultural chemicals will have on their health, their workers and their consumers,” he said. “If conventional farming is seen as more profitable, it will only be those with a personal motivation that will switch to agroecological practices,” he said.

“The bugs all have to eat, too. Instead of seeing them as enemies, we try to see them as allies,” he said, adding that he located other plants nearby, like tobacco, to keep the bugs away from the crops.

Because of these more complex measures, farming this way is more expensive than conventional farming, but there is real economic opportunity here, too.

Related: A push to legalize coca leaf production in Colombia

Osorio is also now earning a good income from welcoming tourists from across Colombia and around the world, teaming up with Simon Willis, the director of a tourism company, Kagumu Adventures, which brands itself as carbon-neutral, socially responsible and economically sustainable.

“Travelers get the chance to meet a traditional farmer and hear his remarkable story,” Willis said. “This allows guests to witness where their food comes from and also see the impact their food choices have on the environment, their health and the health of the farmer.”

Osorio also runs a restaurant, cafe and produce store called La Hojarasca Cultura Orgánica in the town of El Carmen De Viboral, where they sell farm produce, artisanal cheese and other “value-added farm products” such as homemade pasta, cornbread and pizza bread

But he says consumer education is needed, as well.

“People have been trained to look for the brightest colored and biggest vegetables. We focus on the nutritional value rather than the aesthetics.”

“People have been trained to look for the brightest colored and biggest vegetables. We focus on the nutritional value rather than the aesthetics,” he said, adding that it’s more expensive to buy his produce than what is grown out of conventional farming methods.

Related: New companies want to deliver ugly produce to your door

“Here in the store, we sell for about an average of 20% more than other produce stores, but down in the city, in Medellin, the prices can be two to three times more expensive to buy agroecological produce,” he said.

Despite efforts like Osorio’s to promote permacultural practices that reduce and eliminate health risks, Colombian President Iván Duque Márquez is trying to restart a program that uses planes to spray highly concentrated glyphosate herbicide (known in the United States as Roundup) onto crops of coca — the precursor to cocaine.

According to Adam Isacson, director of the Defense Oversight Program at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), the program began in 1992 and was stopped in October 2015, eight months after the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) put out literature determining that glyphosate is probably carcinogenic.

Isacson said in his mind, there’s little doubt that prolonged exposure to glyphosate is bad for people’s health, especially in light of the billions of dollars awarded to plaintiffs in glyphosate lawsuits in California over the past year or so, part of more than 13,000 lawsuits lodged in the US in relation to Roundup.

“This does make the optics bad, and the Duque government is getting around it by claiming the situation is dire with record coca cultivation, that they’re going to comply with the Colombian Supreme Court’s restrictions, and that this will probably be a more limited spray program than in the mid-2000s, focusing on what they call ‘industrial’ coca plots,” he said.

Meanwhile, Osorio continues using his alternative farming methods and connecting curious travelers to the land. He knows many farmers aren’t about to change their practices, but he believes that continued education on the health benefits of agroecological methods will make a difference.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?