Allan Manuel, a 22-year-old photo lab technician drafted into the Korean War, remembers the sound of machine gunfire breaking the night’s silence in an abandoned neighborhood in Seoul.

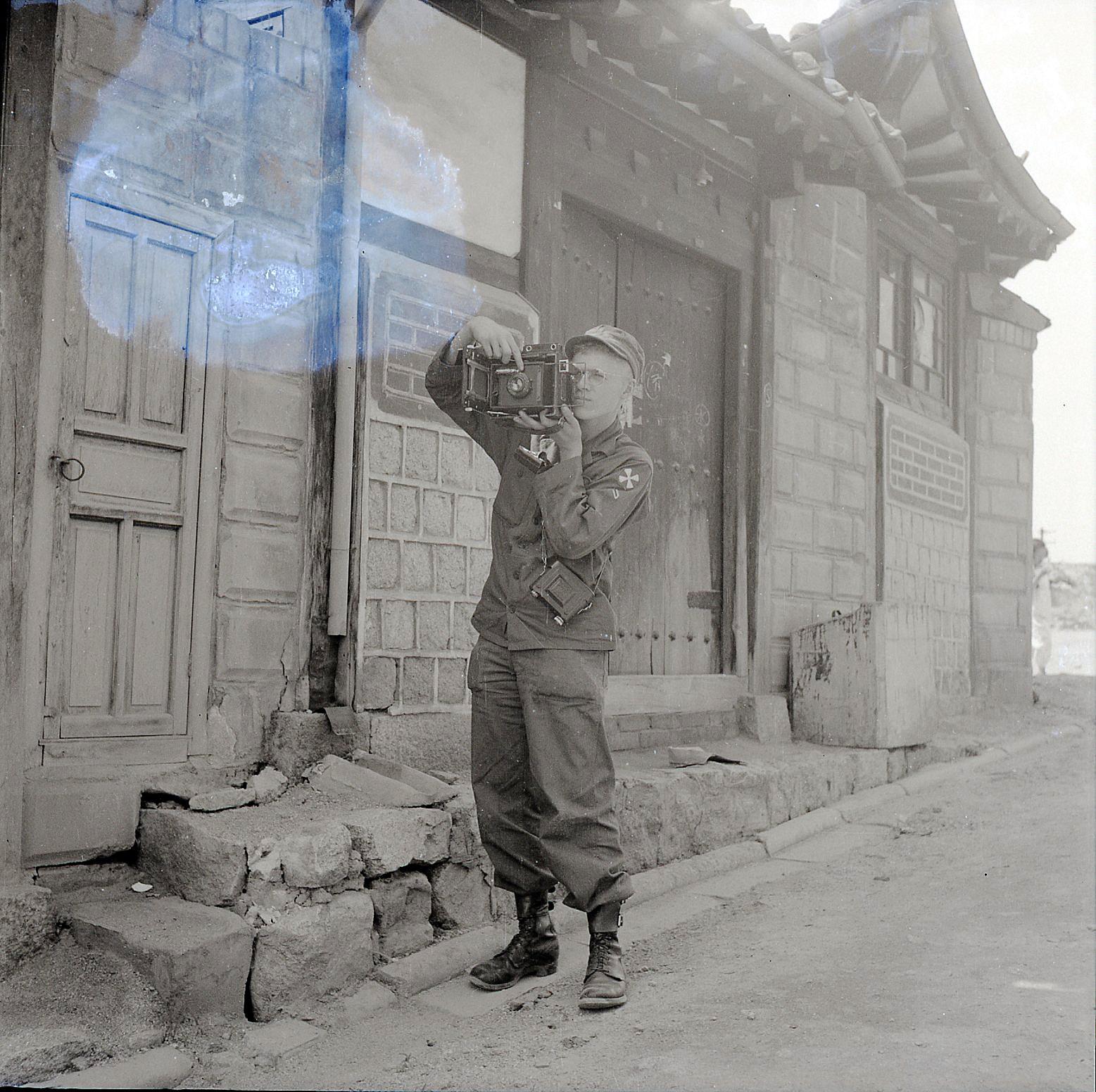

He and other members of the US forces were squatting inside empty houses. Allan Manuel — normally armed with a camera, not a gun — peered into the street from the doorway.

It was the Newport, Rhode Island, native’s only known encounter with battle, but it stayed with him some five decades later. The year was 1952.

“There was nothing to see. All remained quiet,” he recalled in an autobiographical essay written in 2003, which his son held onto for years. “Someone whispered [about] getting the one thing we had plenty of — an empty beer can — [and] he threw the can out onto the street with a clatter. The can was met by a burst of machine gun fire, and it went dancing down the street.”

They never found out who fired those shots. But Manuel, who faced potential battle with only eight bullets to his name, made sure that he stuffed his footlocker full of ammunition from then on.

“There was hardly any room for my clothes,” Manuel wrote. “But I’m happy to say that all my ammo was still there in my locker when I returned home to my wife and infant son.”

Related: What can satellites reveal about North Korea’s missile and nuclear sites? Not enough.

This is just one forgotten moment of the famously “forgotten war” — the Korean War, which ended in a ceasefire in 1953. It’s still technically ongoing, even as President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un keep an open dialogue after two face-to-face summits. It’s a war that brutally claimed nearly 36,574 American lives, plus some 2.8 million more across all countries involved.

Now, Manuel’s son — 58-year-old Paul Manuel — is sifting through his father’s never-before-seen photos of life during his nine-month service between 1951 and 1952. They don’t illustrate a complete picture of the war, but they do reveal much about vibrant life on the Korean peninsula in a time of overwhelming death — and when most were certainly suffering.

“These photos are just phenomenal to me,” Paul said. “It’s like, wow, this is a part of my father’s life I didn’t really know anything about.”

Forgotten wartimes

Despite holding onto these photos for decades, Allan Manuel didn’t appear to think about the Korean War.

“He didn’t really talk about it,” his son, Paul Manuel, said. “He would put slides [of the Korean War] up on the screen when I was really little, but I don’t remember them and I didn’t really care.”

It wasn’t until Allan Manuel started to lose his eyesight and his memory that the photos truly resurfaced. He started filing them into folders on his computer, perhaps to revisit his memories and preserve them. Then, about six years ago, Paul started collecting them as his father’s health declined.

“I’ve been trying to save everything I can. … I just thought, ‘Wow, these are incredible,’” Paul said. “He and his friends would go out around Seoul, take pictures and just meet with people and talk with them.”

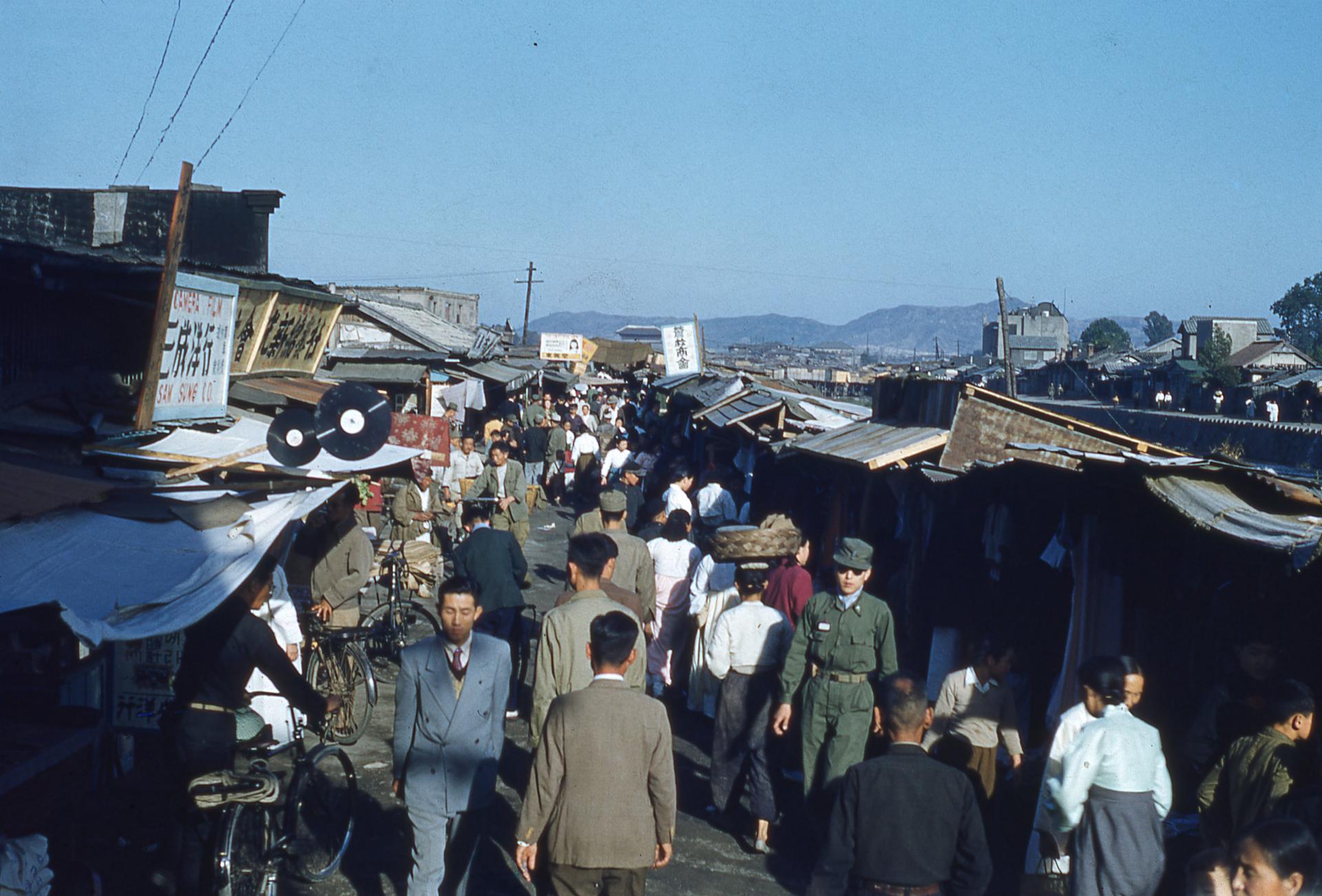

The photos show rubble, ruins, soldiers marching in towns — but also children at play in rivers and outside of US military bases. They show American and South Korean soldiers working on the underbellies of cars, or elderly women selling vegetables in shi-jang street markets.

Life during the Korean War was exceptionally hard for all parties involved. And in a sense, Allan Manuel’s photos show that — but with dignity, if not a touch of optimism.

“You can tell the photographer was really interested in the people in Korea and not in a demeaning, exoticizing kind of way,” said C. Harrison Kim, a professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and author of “Heroes and Toilers: Work as Life in Postwar Korea.” “I think he wanted to show Koreans in a rather happy, kind of communal life.”

“What’s interesting is that he photographed the National Science Museum, which is completely bombed out, but he also went to tiny little villages to take these photos,” said Jung Joon Lee, an assistant professor of history and theory of photography at the Rhode Island School of Design. Jung has seen thousands of Korean War photos over the course of her career. “Perhaps in his personal archive, he is trying to encompass the direct hit of war on Seoul, but also how the local life still continues. That’s quite fascinating to me.”

As Jung put it, images left behind from any war contribute to the modern “memory-making” of it — and these photos, if anything, appear to have a “selective memory” that leaves out the horrors of war. But Allan Manuel, now 89, worked night shifts developing images for assigned photographers, venturing out to take photos only when he had a spare moment. At times, that meant taking snapshots of obliterated buildings and shantytowns. But usually, Manuel captured vignettes of city life and portraits of people who often posed for money.

“There were brutal pictures that he would develop, but he never really talked about what was in them,” Paul Manuel said. “You know, he just said that they were tough to develop at times. I remember he mentioned one of a person who was decapitated by a train — really terrible.”

History revisited

Manuel’s never-before-seen photos certainly capture moments of history unfolding. Some shots show President-elect Dwight D. Eisenhower’s visit to Seoul in November 1952, with a trolley bearing flowers and a celebratory welcome message.

The images also repeatedly show grinning houseboys — poor children (often orphans) who lived on military bases and picked up odd jobs running errands or shining shoes for soldiers. The history of houseboys is both heartening and problematic: Young South Korean boys often befriended the American soldiers and some were even adopted by families in the United States, but the subtext of servitude was nonetheless present.

“From the streets, these kids found some kind of shelter and a role where they could earn a little bit of money, some food and some kind of protection. It seems like most American soldiers actually liked these kids and they took care of them,” said Kim of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “But ethically and morally, it became a problem. It was, at the same time, a very racist and colonial-like practice.”

Based on his photos and notes about them, Allan Manuel befriended at least one houseboy, likely named Han Sung-yal, who appeared in several of his photographs.

Related: A Korean adoptee meets his birth mother and winds up moving in with her

“I’m seeing one boy appear three times, so I’m wondering if Mr. Manuel had a personal connection with this boy or if he lived in the military unit he belonged to,” Lee said. “Children were always favorites in photos by war photographers, in general, and not just with the Korean War. But during the Korean War, there was a historical layer added because a lot of [these children] were brought to the US as adoptees, and the trend of transnational adoption continued.”

Related: 30 years later, this Korean adoptee finds ‘home’ again

More than 100,000 Korean children were adopted to the United States after the Korean War, setting in stone a trend that still remains somewhat controversial. Poor record-keeping and other haphazard practices have left an estimated 10% of Korean adoptees stateless, and some have been deported by the US back to South Korea — a country they didn’t grow up in — in recent years.

Related: For many, international adoption isn’t just a new family. It’s the loss of another life.

But beyond documenting the beginnings of adoption culture and a complex relationship between military men and young Korean boys, Manuel’s work also unknowingly captured a South Korean life before its rapid “miracle of the Han River” — the economic transformation of the 1970s and 1980s.

“The fans of, let’s say, [K-pop band] BTS would not imagine these kinds of images [of South Korea], right?” Jung said. “Obviously, South Korea has changed a lot and, if you will, incredibly. [Photos like these] are often used as a reminder of how different and poor and tragic Korea was. It gives them pride. It gives them a history lesson that this could happen again.”

Related: 60 years before BTS, the Kim Sisters were America’s original K-pop stars

These photos illustrate a part of the Korean peninsula’s complicated past. They reveal a legacy of war, wreckage, violence and the power dynamics between South Koreans and Americans at that time. Much has changed since the Korean War began. And with peace talks set to take place among South Korea, North Korea and the US, further change could be on the horizon.

“[These photos] are so fascinating to me. It’s a world and a life that is completely foreign to me — scary, even,” Paul Manuel said. “And I do find these times hopeful. I really do. I’m not educated in foreign affairs, but I just see hope that people never had before.”