A money changer poses for the camera with a US hundred dollar bill and the amount being given when converting it into Iranian rials at a currency exchange shop in Tehran’s business district, Iran, Jan. 20, 2016.

Things That Go Boom is a co-production of PRX and Inkstick Media, and is a partner of PRI’s The World. This season, the podcast digs into backroom negotiations and political ploys and asks: Is American foreign policy doing its job? Listen and subscribe to the podcast to hear the whole story.

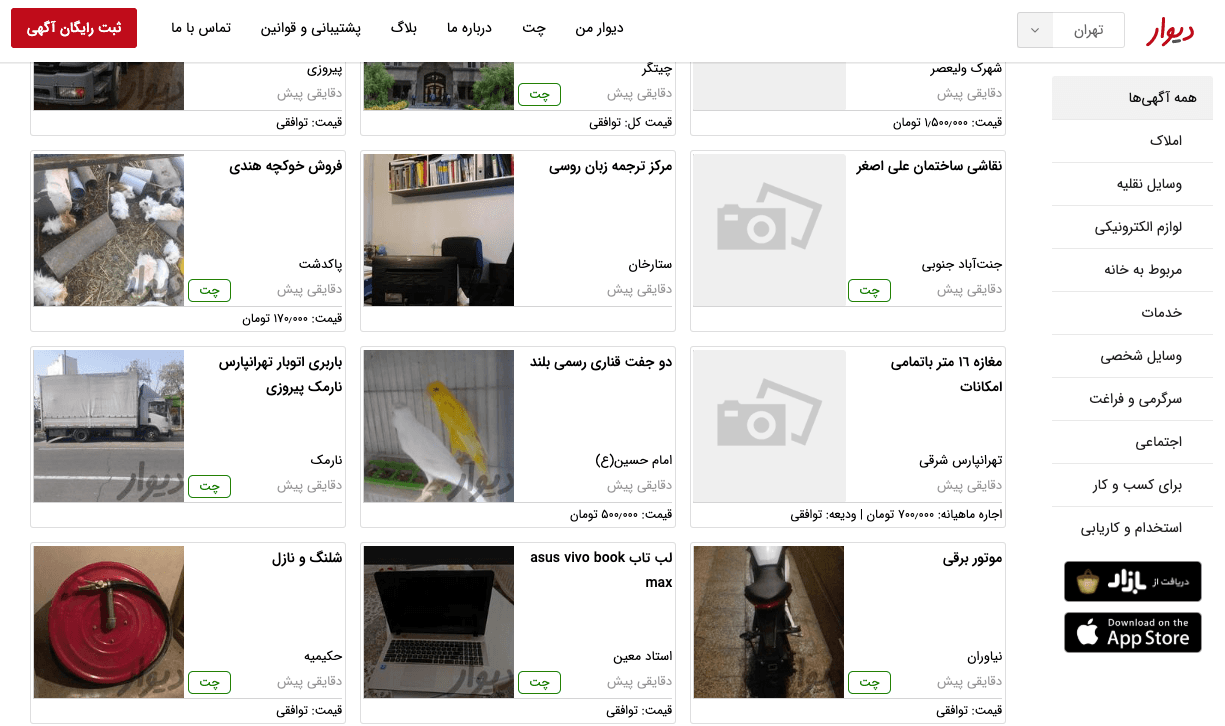

In Iran, you can buy almost anything — including a purebred Pomeranian dog — on a site called Divar.

The Iranian version of Craigslist, Divar has become a place for Iranians to offload their possessions as they get ready to emigrate from the country.

When United States President Donald Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, he also sent Iran’s economy into a tailspin by reimposing tough sanctions. Iran maintained its end of the deal for a year, but on Monday, June 17, it announced it will have stockpiled more enriched uranium than the deal allows by the end of next week — opening the potential for a nuclear weapon. And as political tensions and economic hardships escalate, some Iranians are opting to leave.

Sanctions limiting trade have squeezed the Iranian economy for years, and while the US says it’s targeting the regime, it’s the Iranian people who are suffering.

Fatemeh Jamalpour is a journalist based in Tehran. She says she’s seen and spoken to people selling some unconventional things on Divar, from cosmetics to gravesites — yes, gravesites.

“I think if you sell your house that’s one thing,” Jamalpour says. “You are saying goodbye. But if you sell your grave you’re basically saying goodbye for eternity.”

The man Jamalpour spoke to about his gravesite told her he used to own a car dealership, but because of sanctions, he can’t acquire cars to sell.

“You know, the US sanctions affected car manufacturers in Iran a lot because they can’t import the car parts,” Jamalpour reports. “And he had to sell his dealership and now he wants to join his family members who live overseas in Canada.”

Some Iranians are leaving the country’s troubled waters but others are riding the wave.

“Whatever doesn’t kill you just makes you stronger,” says Alireza Jahromi, 47. “So far, we are not dead.”

Jahromi is a partner at an IT firm that started a chic new burger chain in Tehran called Frikadell.

“Thank God we don’t have McDonald’s here,” he says. “There is more room for us to be more creative.”

Despite a largely unenforceable country-wide ban on social media, Frikadell is a chain built for the Instagram era — complete with an app and a gimmicky, photo-friendly box that keeps ingredients separate until they are ready to be eaten.

The app lets you name a burger after yourself and then your friends can order it, too. You can even promote your burger on social media for points.

“I will choose a name for it. Put it after my own name, Alireza,” Jahromi says. “And then, boom, it’s finished.”

Since Trump reimposed sanctions on Iran, Jahromi says Frikadell has had to rethink its supply chain and its prices. A burger, fries and drink from Frikadell is a good value in Tehran but a steal in dollars since Iranian currency has plunged.

“I think two dollars, yeah,” Jahromi says. “Two dollars! Nobody can compare with that.”

Inflation in Iran is skyrocketing, says journalist Fatemeh Jamalpour. Medicine like Prozac and some cancer drugs are almost impossible to come by. Even ice cream costs five times as much as it did six months ago.

Jahromi, the Frikadell entrepreneur, says the sanctions are like a tsunami.

“It’s all about your experience that you’re going to run toward the wave or run toward the hills,” he says. “If you’re a surfer, if you know how to deal with the wave, you’re going to take that and use all of its forces to enjoy.”

Jahromi is paddling right into the waves. When Frikadell was suddenly priced out of certain ingredients because of the sanctions, Jahromi says they started to look locally. He turned to a friend who had a small business cultivating cacti in a greenhouse.

“So I told him, ‘How about not doing the cactus and doing jalapeños for us?'” Jahromi says.

Frikadell now buys equipment and ingredients locally. Jahromi says he’s even looking toward exports instead of imports.

“The best thing that we have in abundance is ideas,” he says. “It’s not oil. It is our manpower, it is our brainpower.”

How do sanctions on Iran really work? Subscribe to the Things That Go Boom podcast for the whole story (it includes pie!) and hear why Iranians weren’t all that surprised about America’s U-turn on the nuclear deal.