Morocco’s ‘mule women’ risk their lives hauling goods across the border from Spain

Women in rural Morocco say they turn to work as porters for short stints — six months to two years — and the grueling hours and demands have started to take a toll on their lives. But ferrying goods between the border from Africa to Spain is one of the few opportunities available.

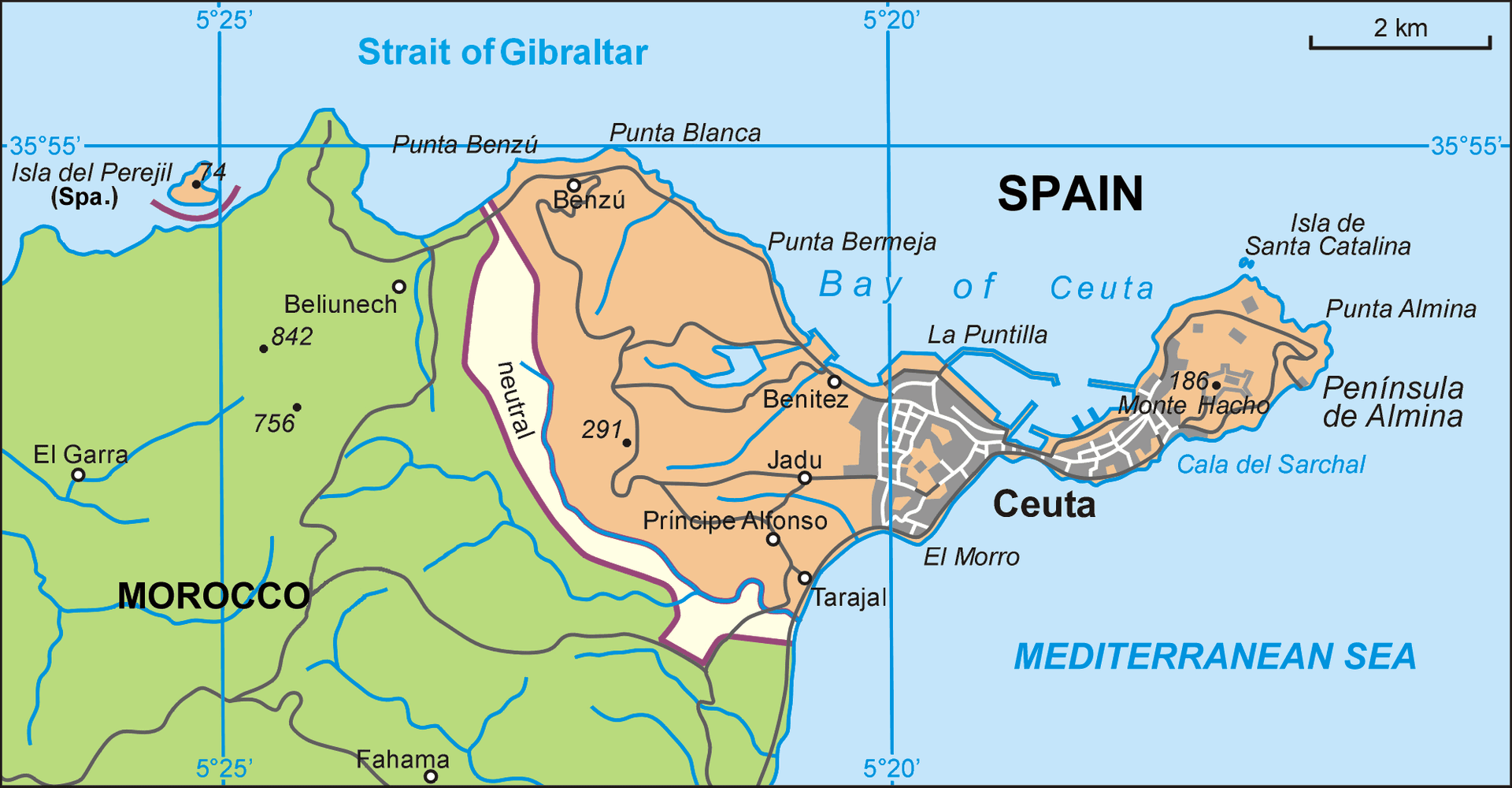

Aziza clutches a flimsy piece of white paper in her hands. As a porter, this is the “golden ticket” that grants her the right to enter and leave the industrial zone of Ceuta, Spain.

Known as a “mule woman,” Aziza, 30, carries a load of goods across the border to her home in Fnideq, a rural village in Tetouan, Morocco — about 4 miles from the border.

It’s just a 15-minute walk, but Aziza makes sure to arrive the night before, around 10 p.m., when the women start to line up at the metal gates that swing open around 6 a.m. every morning. As porters, their main goal is to transport blankets, baby goods, car tires and more back and forth — up to seven times a day — between Spain and Morocco.

In early 2019, the El Tarajal business association within Ceuta’s manufacturing hub implemented this new ticketing system after several “mules,” who were mostly rural women, were trampled to death.

Aziza works alongside porters Daouia, 42, Zora, 48, and Fatima, 41, all women who asked not to use their full names due to fear of reprisal. On a short break, they sit on steel carts while eating a simple lunch in a garbage-strewn alleyway. They share a common story of struggle: Each has a limited education, come from rural communities in Morocco near the Spanish border, are either divorced or widowed and all support children.

Related: Forty-seven people died crossing the Mediterranean in a wooden boat last month. This is their story.

They say they turn to work as porters for short stints — from six months to two years — and the grueling hours and demands have started to take a toll on their lives. But ferrying goods between the border from Africa to Spain is one of the few opportunities available for rural women.

Only one-quarter of rural women work in Morocco, according to a 2018 report from the International Labor Organization, a UN body that promotes decent labor standards. Women employed by a company make up just 3%. And in rural Morocco, gender roles demand that women care for their families first; outside employment is a second thought.

Related: The fence separating Europe from Africa might be coming down

Although the Moroccan government has implemented changes by expanding education opportunities for women and girls and revising their Family Code in 2004, daily reality has not changed for most.

And so Aziza and her workmates head to Ceuta, an autonomous city and military outpost with about 85,000 residents and a longtime gateway for essential goods due to its strategic position in mainland northern Africa.

The city’s prosperous palm-studded center, approximately a 20-minute drive from the border, is populated by military families and merchants — and it’s a far cry from the polluted manufacturing areas nearer to the border where the porters work.

Residents from Morocco’s Tetouan region don’t need visas to enter Ceuta’s industrial area, which is about a two-minute walk from the border. Porters cross over and head straight to El Tarajal, the vast manufacturing complex just across it, to load up on items from various vendors — selling a plethora of products — to bring back to Morocco.

When porters transport items on their person, vendors avoid a customs tax and the workers receive a small payment for their service.

To exploit this loophole, porters are paid around $3.30 to $5.60 for each backbreaking 132-pound load they successfully bring across on their backs. In one day, porters can make an average of $22 to $28. These prices can go up if the borders tighten with checkpoint closures due to attempts to control illegal migration crossings into Europe.

Crushed to death

A lack of systems to manage the flow of workers on any given day poses serious threats. Between 2017 and 2018, at least six female porters were crushed to death.

Zora says she will never forget the deaths she witnessed. In January 2018, she was waiting in line to cross for another day of work when one Moroccan policeman guarding the border hit one of the workers with a belt.

Packed together and frightened of more violence, the porters started to run, creating a stampede. They got trapped in the narrow, confined space defined by a fenced barrier that leads to the crossing point; they must enter the industrial area through revolving steel-barred doors. On one side, Moroccan police monitor the porters; on the other side, Ceuta police and private police wait to process them. Carrying heavy loads, the porters are pressed together until they pass through the other side.

To control the melee, more police began to take off their belts and hit the porters. Fear surged through the crowd and panic ensued as the porters tried to flee. At least two women were killed in the crush.

“I thought I was going to die.”

“I thought I was going to die,” said Zora, 48, her eyes still wide with fear as she recounted the story more than a year later. But Zora, who has been working as a porter for two years, says she had no choice but to return. The mother of three children, she is a widow and doesn’t know how to read and write.

“There is nothing for these women in Morocco. There is no medical attention, no education, no opportunities,” says Redudante Mohamed, 42, a volunteer member of DIGMUN, a nonprofit organization based in Ceuta. Funded with a mix of public funds and private donations, DIGMUN provides education classes and assistance for Moroccan women and children in the region.

In 2017, members of the European Parliament asked the body to answer questions about with the dire situation at the border. In a written response, Dimitri Avramopoulos, then-commissioner of the EU’s Migration, Home Affairs and Citizenship committee, stated that responsibility lies with the respective governments.

“There is nothing for these women in Morocco. There is no medical attention, no education, no opportunities.”

The following year, EU Parliament member Beatriz Becerra Basterrechea raised the plight of the mule women again. She has yet to receive an answer.

During a Spanish parliamentary debate on the issue, Ione Belarra, spokeswoman for Spanish political party Podemos, meaning “We Can,” stated it was “absolutely essential” that measures be taken to curb the “human exploitation” of the thousands of “mule women.”

Yet the stampedes continued with no government intervention.

Related: For these girls in Morocco, a tech camp presents a rare opportunity

So local police, merchants and NGOs decided to limit the number of entries to 4,000 a day and separate the men and women streaming across the border in hopes it would reduce pushing: Men can only pass on Tuesdays and Thursdays and women on Monday and Wednesdays.

A few months after the January 2018 deaths, the El Tarajal business association proposed another solution to mitigating the risk of stampedes: wheelbarrows.

The sturdy steel boxes with wheels and long handles were made in metal shops in Morocco, at a production cost of 10-15 euros each, which the porters have to pay. Their shape provides enough space between the women as they gather in lines and helps halt the pushing and shoving. Previously, the women would have had to carry everything on their backs as foot porters to be exempt from import duties.

The new ticketing system has also reduced the potential for stampedes. At $2.20 per ticket batch, purchased by the merchants from El Tarajal, they are zealously guarded by everyone in the chain from porters to merchants and private guards. But the porters face the most risk — they must pay the ticket fee if they lose it before they can enter or exit.

With the income generated by tickets, the association pays for extra private guards to patrol and maintain the area. The tickets and extra security has eased tensions — there has yet to be a death in 2019, said the women — but they are still eager to leave the hardships of porter life behind.

“We want to be educated, speak more languages, have more money, but there is nothing else available.”

As Daouia packed her cart high with goods and readied her exit ticket, she explained why she continued to trudge back and forth between the border:

“We want to be educated, speak more languages, have more money, but there is nothing else available.”