Forty-seven people died crossing the Mediterranean in a wooden boat last month. This is their story.

Before attempting to cross the Mediterranean, migrants often stay in camps like this in Morocco.

“Most of the bodies were floating face down. Some wore life jackets. But there were a lot of life jackets without any bodies inside. At first I saw just one body, then another and another and another. It was terrible. It’s a moment I’ll never forget.”

This is the memory of the crew member who first alerted Spanish Maritime Rescue to a capsized boat on Feb. 4. He was working on a ferry en route to Melilla, one of two Spanish enclaves still remaining in northern Africa. The ferry is part of Trasmediterránea’s large fleet and makes a daily trip between Melilla and Almería, on the Spanish mainland, carrying up to 1,250 passengers on each crossing.

Some 4,000 miles away, my cell phone started ringing. I spent most of the following week on the phone with families across West Africa who were desperately searching for any information about their loved ones.

My son, is he alive? My wife, have they found her body yet? When will we know? How will we know? Is anyone looking for them?

For tourists seeking a day-trip to Morocco, there are a host of ferry options from Spain — most take 30 minutes and cost 25 euros per passenger. For African migrants, refugees and asylum seekers seeking the chance at a better life in Europe, there are a host of smuggling options running the same routes in reverse. Most take a full day’s journey at sea and cost an average of 2,000 euros per passenger.

Boarding one of Trasmediterránea’s new ferries, you might notice a small sign warning you of seasickness. Boarding one of the small wooden fishing boats that smugglers captain from Morocco’s coast, migrants don’t need a sign warning them that, as one 15-year-old boy tells me, “You’ll make it to Europe or you’ll die trying.”

A difficult process

After being alerted to bodies floating in the open sea, Maritime Rescue sent a ship from Melilla to begin searching for survivors, and the Guardia Civil launched two smaller rescue missions as well. In the hours that followed, the Royal Navy of Morocco ended up recovering the majority of the bodies, which had drifted to their coastline by the time they responded.

The officers placed 20 bodies in one massive, blue plastic bag made for tragedies like this and took them to El Hassani Hospital in Nador. The one body recovered by Spanish police was taken to Melilla. At the morgue, I was told recently, 16 of the 20 bodies remain unidentified.

“We have a poster hanging in the police station in Nador with pictures of each face, so the families can identify them," an official said.

But their families aren’t in Morocco, and the friends of these victims live hidden in forest camps that are routinely under attack by Moroccan police, who threaten to beat, imprison or deport anyone found. The lack of official reporting by Spain and Morocco means family members are left with more questions than answers, often learning about the passing of loved ones from Facebook posts months after an incident has occurred.

A short, dangerous crossing

Morocco offers the shortest passage to Europe of any African country — less than eight miles across the Mediterranean Sea — and the Spanish enclaves of Melilla and Ceuta make it the only country on the African continent to share a land border with the internally borderless EU.

It is one of the most trafficked border regions in the world right now, with the number of people attempting to escape violence and poverty across West and Central Africa growing daily. The closing of other primary routes to Europe in Libya, where migrants are now being bought and sold in an emergent slave trade, is pushing more people to Morocco’s borders.

But the steady reinforcement of the Spain-Morocco land border, which is now secured by three rings of 20-foot high razor-wire fences and under constant surveillance by the Guardia Civil, means even more are attempting treacherous sea crossings.

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the number of migrants reaching Spain by way of the Mediterranean tripled to nearly 22,000 last year, and the number of reported drownings off the Spanish coast doubled. However, the 223 drownings reported in 2017 only account for bodies that were recovered and identified.

Less than two months into 2018, there have already been 75 victims recovered, including the 21 found floating off the coast of Melilla last month. How many others remain in the water?

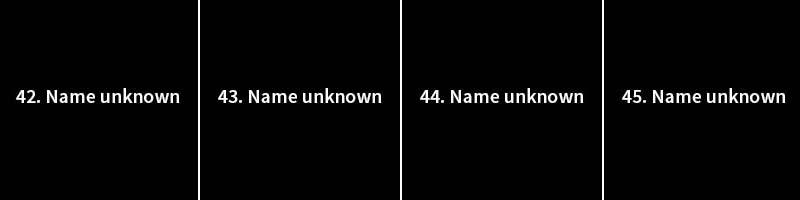

No names

The week of the incident, major news organizations from The New York Times to El Mundo covered the latest Mediterranean tragedy, but regardless of which source you follow, you read the same facts.

Twenty-one bodies. All African migrants. All packed into a small wooden fishing boat that capsized off the coast of Morocco’s Spanish enclave.

There was no follow-up as the victim count edged upward, ultimately winding up more than double what was originally reported.

As I followed the coverage by various sources, I noticed there was never a single name released.

Who are all of these people, assigned numbers, not names, in the morgue? Where were they coming from, what had driven them to their final crossing, and what had they expected to find on the other side?

I needed more than a number. I didn’t want to simply break the news that it was 47 migrants and two smugglers, not 21 people, who were lost at sea. I wanted to report who had been lost. I enlisted the migrants still living in Morocco’s hidden camps to help me collect names, faces and stories. They knew better than anyone the group who left just after nightfall on Feb. 3 to walk 16 miles to the meeting point their smugglers had given them.

An anthropologist by training, I started working on issues of migration and international human rights a decade ago and have spent many years living in the hundreds of makeshift camps around primary departure points in Morocco, Algeria and Libya. The first time I gained access to Carrière — one of Morocco’s largest and most tightly controlled camps — was when I was working on another story for PRI in the summer of 2016.

It was a complicated process requiring permitting at the governmental level and clearance at the local level — from the smuggling rings that control the space and the brotherhoods of migrants themselves.

I spent the following year in the region finishing a documentary film that captures the journeys of three migrants from Guinea, Mali and the DRC to their final attempted crossings. I was back in Carrière as recently as last month. In fact, I had only been back in the US for a week when I received my first phone call alerting me to the capsized boat carrying people I knew well.

'Smart, brave, generous'

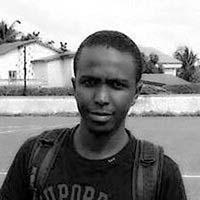

The photograph of Abdul Karim Barry — a 17-year-old boy from Guinea — was one of the first I saw.

Karim had been in Carrière awaiting his chance at crossing for over two years. He left his home at the age of 15 and traveled more than 3,000 miles alone — from Guinea to Morocco. After his father died, he felt responsible for taking care of his younger brothers and sisters when his mother couldn’t find any way to support the family in their rural community. He wanted to give his siblings the chance to go to school like his father had given him.

“Karim was smart and brave and above all, he was generous,” one of his closest friends, Mamadou Bah, tells me over a crackling phone line. “He always struggled for the well-being of the group, even risking the dangers of going into the street to beg for us when we couldn't find enough food to eat. It was Karim who prepared the one daily meal for our brotherhood every night.”

I posted a photograph of him and asked his friends in Morocco and Guinea to help me make him more than a number.

“Karim studied hard before leaving home,” Thierno Jalloh wrote, “and he used his education to speak up for the other boys who didn't have any. He was young, but he was a natural leader with a big heart. He couldn’t stand for anyone to be treated as less than human because of the color of their skin.”

Abdoulaye Barry wrote, “He told me he dreamed of becoming a soccer player when he was little. He played on a team in Guinea, and he was really good. But as you grow older, you realize some of your dreams won’t ever be realized. Still, Karim played with me in the forest sometimes. We had a ball we made out of plastic and tape.”

Rough conditions

In the hours before the first bodies were spotted, Karim, along with 46 men, women, and children coming from Guinea, Cote D’Ivoire, Cameroon, Senegal and Mali left their camp in Carrière. Their smugglers, two Moroccan men, were waiting for them on a rocky beach in Arekmane.

They carried a small wooden fishing boat that had been rigged with an outboard motor down to the water. A witness who traveled with the migrants but didn’t board the boat that night said the winds were too strong for a safe crossing — 50 mph, according to official reports.

So why would smugglers choose to travel, risking their own lives, under such rough conditions?

In previous years, they wouldn’t have. But new systems created to protect migrants’ financial investments have made tragedies like this one significantly more likely. In 2016, I knew dozens of migrants who were devastated when they paid 1,500 to 2,500 euros and failed to reach the other side. This left them trapped in Morocco for many more years, struggling to save up enough money to try again.

This past summer, I noticed a niche market had emerged with some smugglers stepping into the business of transferring money from migrant to smuggler — only after they had safely reached Spanish soil. For a 10 percent increase in fee, migrants can now pay these third parties and secure their investments.

Those who find themselves back in Morocco after a boat has capsized or a police vessel has re-routed them, as happens more often than not, have the money to try again.

For the smugglers who captained the boat on Feb. 4, a postponed departure would have meant approximately 96,000 euros returned. Another factor: The witness explained how smugglers often call for last-minute departures when bad weather is on the horizon, knowing storms make it easier to evade surveillance efforts by the Guardia Civil.

With an overcrowded boat and waves reaching three meters high, they capsized less than an hour into their journey. The passengers were thrown into freezing water without enough life jackets — many of them not knowing how to swim. The oldest reported passenger on board was 34, the youngest had just turned 14. There were at least eight women, one of them pregnant.

Lone survivor

Two days after the tragedy, the Royal Navy of Morocco reported that, miraculously, one young man from Mali had been found alive. After a series of interrogations, he was accused of taking part in an illegal operation and is currently being held in police custody.

The Nadori police told me they are continuing to search for the top-level smugglers thought to have masterminded this operation and many others like it.

Photographs, names and questions have poured in ever since. Along with them, I received final videos that were recorded by young men like Mamadou Diallo, 21, who tells his mother, “I’ve suffered greatly in my journey to Morocco, but it’s all been worthwhile because, soon, I’ll be calling you from Spain.”

And Safourata Sow, 28, who tells her three daughters how much she loves them and misses them.

Again and again, I listened to the words of Karim, who was one of the last boys I interviewed in person. Sitting by his makeshift tent he tells me, “We've traveled so far, we've been through so much, I finally understand what my brothers meant when they told me, 'I'll make it to Europe or I'll die trying.' After you've endured the horrors of this journey to Morocco, there's only one way home.”

Given the lack of access to basic social services and the active fighting in some communities in West Africa, it is not uncommon to hear of boys like Karim traveling thousands of miles north in search of a way to support their families. Hassane and Houseine Traoré — 28-year-old twin brothers from Cote D’Ivoire — had a similar story to tell.

“They were the coolest guys,” says an old friend, Stephanie Dokou, who grew up with them in Cote D’Ivoire. “They were the best athletes our village had ever seen, they played music and sang, they did well in school. All the girls loved them. We knew they would go on to do great things.”

“They were always together,” explains another old friend, Y’souf Bella. "One never did anything without the other.”

Including their final crossing to Europe. Both boarded the boat, neither body has been found. Their mother calls me every day in hopes I will have some other news. Although Hassane and Houseine were adored in their camp in Morocco, it was difficult for me to track down their actual names for this story, because everyone there knew the charismatic young men simply as “the twins.”

The Traoré brothers were not the only twins, though. Alhassane Barry, 26, from Guinea was also on board.

"Hassane was the quiet one. His twin was the outgoing one. Hassane always looked up to his brother, but, in a lot of ways, it was him who the rest of us admired,” said one of his closest friends, Mamadousaliou Diallo, who made it from Morocco to Europe last year.

“They lost their father when they were young, and they were both devoted to their mother. She worked so hard to be able to send them to university, and they wanted to provide a better life for her. Hassane studied sociology. He was one of the best students in his class, but when he graduated, there was no work for him. In Guinea, it doesn’t matter how smart you are. If you’re not from a wealthy family, you won’t find a good job. He didn’t tell his brother he was leaving, because he didn’t want him to worry. I was the one who called him to tell him about the tragedy. I wanted him to hear it from a friend before he saw Hassane’s photo on Facebook. He couldn’t breathe. I remember him choking back his tears, saying, how am I going to tell our mother?”

The youngest victims

But not everyone had a family at home waiting for news of their safe crossing. Youssouf Diallo, 16, and her little brother, 14, who was the youngest reported passenger on board, left their home after losing both of their parents. In the camps, one of the little boy’s friends tells me he cried when he realized there was no one left to notify of their death.

Youssouf’s friend, Fatima Diallo, also 16, says, “I made a flower necklace and burned it in the fire last night. Youssouf and I used to make them together.”

Some others had family waiting for them on the other side. Tahirou Barry, 24, from Guinea was one of them.

His friend, Hady Cissé, tells me, “He had a beautiful woman waiting for him in France! She was the love of his life. They’d known each other since they were little and got married right after university. Tahirou saved up all of his money to help her get a student visa to study abroad after their wedding. They hoped to eventually both finish their studies in Europe, so they could return home and find jobs before having a family of their own. But Tahirou couldn’t wait another two years to see her, so her decided to cross through Morocco. He was counting the days until he would see her again. She didn’t know he had left.”

Like the newlyweds, Marlyatou Diallo, 26, was crossing to meet her husband, who made it to Germany last year and had fallen ill.

“Marly wasn’t just my sister — she was the smartest, kindest woman I've ever known,” says Fatima, her older sister, who was watching Marly’s son for her until her return. Her siblings passed the phone around, each sharing with me their memories of “the little one.”

“She’ll be missed by all of us,” her brother, Barry, tells me, “But most of all, she’ll be missed by her husband and son, who she loved with all her heart. How can we explain to him how the world took his mother like this?”

Marly’s Facebook page is filled with albums documenting every moment of her son’s life — from his first tooth to his most recent birthday — 5 years old last month.

The last image she posted was perhaps an answer to her brother’s question — it read, “My son — I carried you for nine months in my body and I’ll carry you always in my heart. If there’s ever a day when I’m not beside you, know that my spirit is still there protecting you.”

An incomplete list

I have about 47 students in my lecture hall on Wednesday afternoons. Most of them are the same age as those smuggled across the rough waters of the Mediterranean at night. I have thought about how much attention would be devoted to remembering each of their lives if a tragedy of this proportion ever happened.

For the past two weeks, I have worked tirelessly collecting names and images, and yet I only have 39. There are still family members who don’t know if their loved ones are gone.

Twenty-six lives will never be accounted for in official statistics because no effort was made to recover their bodies from the water. Sixteen of the 21 recovered bodies will soon be dumped in mass graves because no effort was made to identify them in the morgue.

The states involved have no incentive to accurately report high death rates, and before reports can be corrected by media sources, a dozen others have occurred.

In the 24 hours following this tragedy, another boat carrying 39 migrants arrived safely at the Chafarinas Islands off the coast of Morocco, 94 migrants were reported dead in a capsized boat off the coat of Libya, and the Guardia Civil intercepted 31 migrants en route to Melilla. Migration across the Mediterranean is growing by the day.

I hope people stop and look at the faces of Marly and Tahirou, Karim and Hassane, “the twins” and the siblings who had no parents to mourn them. I hope they see there were 47 individuals who packed what few belongings they had on their backs, handed their savings over to smugglers, and stepped onto a small wooden fishing boat to begin their lives. They were proud and eager, like students at graduation.

But no one was there to see all of the work it had taken for them to get to that final crossing — the thousands of miles journeyed across deserts and in the backs of trucks, the years spent sleeping on forest floors, the untold abuses suffered along the way. They stepped onto a boat carrying dreams of supporting their parents and siblings, partners and children.

In all of the years I have spent working in migrant camps across North Africa, I have never met a single individual who wasn't there with the dream of helping someone else left behind. I don't think it's possible to endure the suffering they do unless you have that dream motivating you to reach the other side.

Before the waves overthrew the boat, before he fought for one last breath, I imagine Karim was thinking of how long it might take him to save up for a real soccer ball and if the ground in Spain would feel anything like the ground at home.

I hope people remember their stories the next time they read headlines about overcrowded boats and numbers, not names, of those lost at sea. The headlines never change, as if the same bodies are washing ashore again and again. But how could it be the same twins who brought music to their hidden camp, the same siblings who clung tightly to one another, the same big-hearted boy with dreams of being a soccer player?

Those 47 are gone, soon to be replaced with others, proud and eager.