Without proper intel vetting, could the US be headed toward ‘rushed war’ in the Middle East?

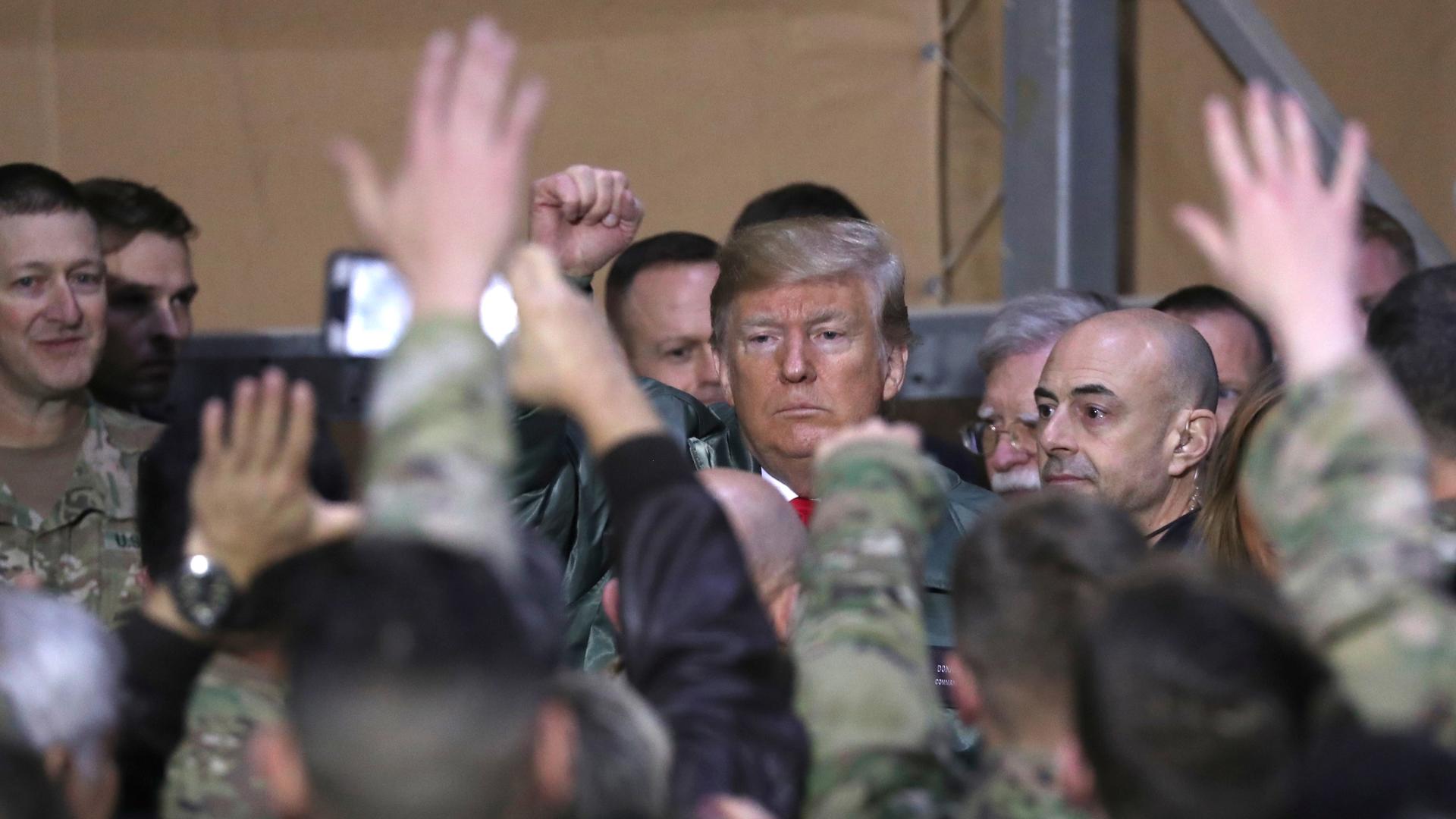

President Donald Trump delivers remarks to US troops in an unannounced visit to Al Asad Air Base, Iraq, Dec. 26, 2018.

The Trump administration ordered the partial evacuation of the US embassy in Baghdad, Iraq, Wednesday in response to what the administration has warned is an “increased threat” from Iran.

The administration has also begun reviewing plans for a military conflict in the Middle East, including one that would reportedly send 120,000 troops to the region.

Related: US pulls non-emergency staff from Iraq amid concerns over Iran

But some US allies have cast doubt on the threat assessment.

“There’s been no increased threat from Iranian-backed forces in Iraq and Syria,” said British Major General Christopher Ghika. “We’re aware of that presence clearly and we monitor them, along with a whole range of others, because that’s the environment we’re in. But as I say, we have no part of Iran in our mission. We are monitoring the Shia militia groups carefully and if the threat level [seems] to go up then we’ll raise our force protection measures accordingly.”

Suzanne Maloney is a senior fellow in the Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. She spoke to The World’s Marco Werman about what intelligence the Trump administration has received about the threat from Iran.

Related: Nuclear deal rollback won’t get Iran a weapon, but it’s not an empty threat

Suzanne Maloney: There is some real ambiguity about that. The White House suggested that Iran is, in fact, planning attacks against American interests or personnel in the region. There has been, obviously, a response in terms of pulling nonessential personnel from the US embassy in Baghdad and there are, of course, reports that the White House is studying military options on Iran.

Marco Werman: Other US allies seem to agree with the assessment from the UK. The European Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini called for maximum restraint after meeting with Mike Pompeo. How can we interpret these responses to the Trump administration’s warnings?

Well, I think it’s quite stunning. I won’t say unprecedented, but it’s highly unusual to see this level of public disagreement between American and British officials since the United States has exited the Iran nuclear deal. There’s been a real effort on the part of the Europeans to try to avoid a full-scale breach with Washington. I think what we see here is a deep sense of foreboding about precisely what the administration is up to — why these nonspecific threats have been publicized and why the United States is taking such fairly noisy action to apparently deter Iran from undertaking any of these attacks. I think, you know, we have a real Transatlantic rift here and there is an effort on the part of our closest allies in Europe to ensure that we don’t find the United States moving down a path that is reminiscent of the war with Iraq.

Do you think it then comes all back to the Iran nuclear deal? Are the sides that are worried about threats and the sides that are calling for restraint defined by who continues to support the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action?

Well, I wouldn’t put it quite that starkly. I think in talking to European officials over the course of the year since the Trump administration exited the deal, they too have suggested that they’re concerned about Iranian actions around the region. But I think there’s also a sense of deep resentment even as European officials seek to maintain some consensus with Washington. Resentment that it is, in fact, the Trump administration’s decision to walk away from the deal and then to impose really severe economic sanctions on Iran that have had a catastrophic effect on ordinary Iranians and on the potential stability of the regime there. That in and of itself has been a precipitating factor to the threat level that we see today.

Related: Iran rolls back nuclear pledges but stops short of violating pact

We have to remember too that there were disagreements about intelligence ahead of the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. So how are we able to evaluate the intelligence this time around and how concerned are you — especially in this age of fake news and disinformation — that casus belli will be especially hard to verify?

Well, I think this is where the intelligence community and the Congress here in the United States and similar institutions in Europe need to really step up to the plate. It is absolutely essential that there is an effort to try to vet the information and make public those details that the Trump administration is claiming justifies any change in our force posture in the region. Unfortunately given the president’s own difficulties in distinguishing between truth and falsehood, I think we have a real credibility problem on our hands. One of the concerns here is that this is a kind of rushed war that isn’t being fully vetted even within the defense establishment. And we saw something similar in the run-up to the war with Iraq. And I think there are real concerns about how serious the plans are and to what extent they’ve been fully shared with Congress. I think that’s going to be a key element of any next steps is ensuring that there is serious congressional oversight.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.