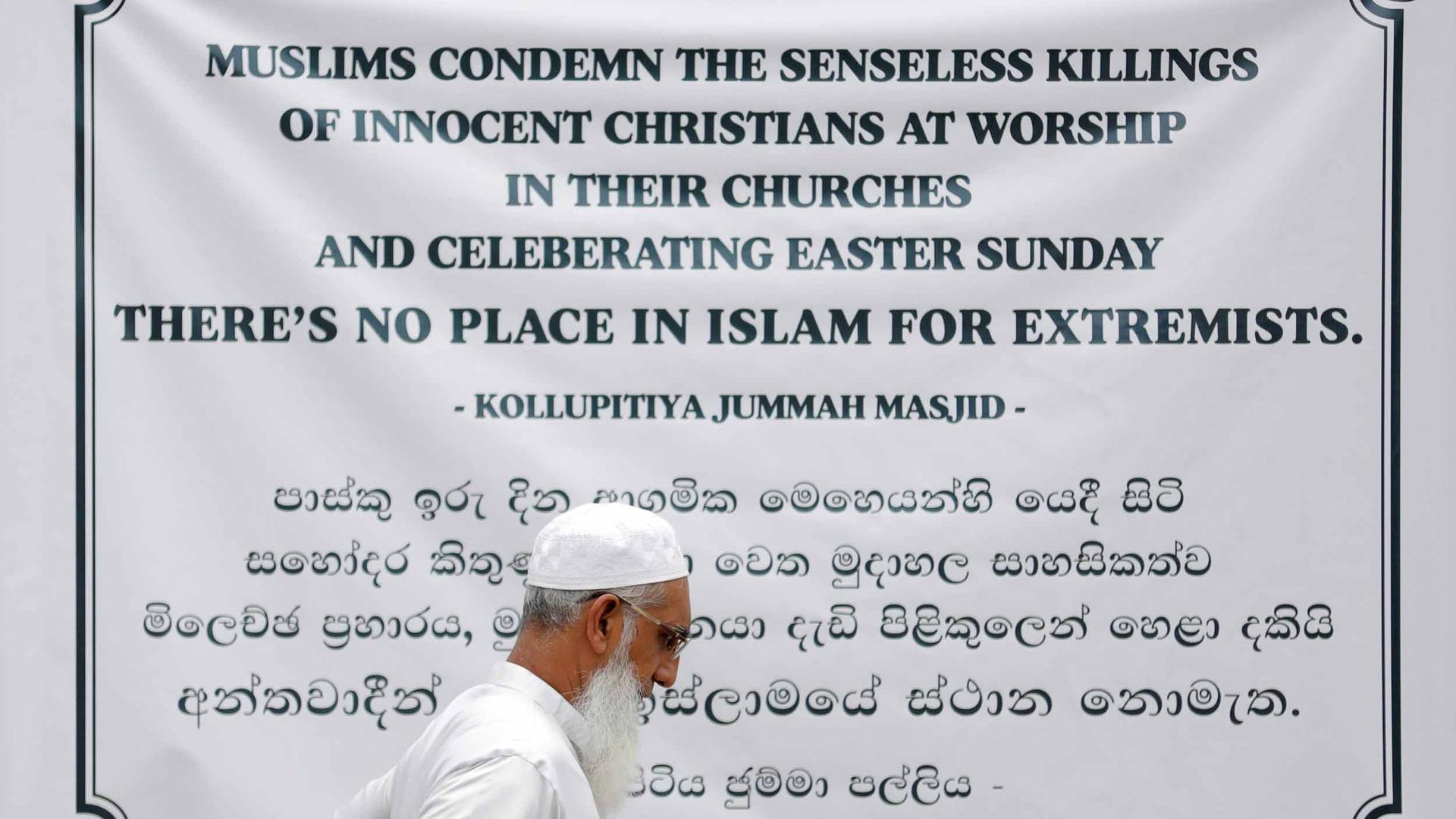

A Muslim devotee walks past a banner on a mosque wall during the Friday prayers at a mosque five days after a string of suicide bomb attacks on Catholic churches and luxury hotels across the island on Easter Sunday, in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on April 26, 2019.

Sri Lankan police are trying to track down 140 people believed to be linked to ISIS, which claimed responsibility for the Easter Sunday suicide bombings that killed 253, as shooting erupted in the east during a raid.

Muslims in Sri Lanka were urged to pray at home after the State Intelligence Services warned of possible car bomb attacks amid fears of retaliatory violence.

And the US Embassy in Sri Lanka urged its citizens to avoid places of worship over the weekend after authorities reported there could be more attacks targeting religious centers.

Related: How the Sri Lanka attacks relate to broader terrorism patterns

Archbishop of Colombo Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith told reporters he had seen a leaked internal security document warning of further attacks on churches, and there would be no Catholic masses this Sunday anywhere on the island.

The streets of Colombo were deserted on Friday evening, with many people leaving offices early amid tight security after the suicide bombing attacks on three churches and four hotels that also wounded about 500 people.

In Negombo, many Muslim-owned shops are closed, and families have shut themselves indoors. Others have said that mobs of people have come to their homes, brandishing sticks or knives. At least one man reported being beaten.

Though most have not been assaulted, the threat is serious enough that the police have taken emergency measures. They’ve bussed Negombo’s Muslims — nearly 600 people — to a community center in a village an hour from the city.

The authorities hoped that taking them there would keep them safe. But the scene at the center was chaotic.

Related: Sri Lanka blasts were revenge for New Zealand mosque killings

A couple dozen people stood outside the gates of the compound, agitated and yelling.

They were protesting the Muslims at the community center, many of whom are refugees from Pakistan.

Someone had hung up signs in Sinhalese and English that read, “We don’t need Pakistanis here.”

The police said the group outside was aggressive and unpredictable. After the crowd dispersed because of rain, the police stayed vigilant. They didn’t know if the crowd would come back or what it might do if they did.

“We don’t feel safe here also,” said Sair Ahmed, one of the Muslims who left Negombo.

He says the anger about the terrorist attacks that are now being directed toward them is misplaced.

“We are innocent people who didn’t do anything wrong.”

“We are innocent people who didn’t do anything wrong,” he said. “I feel pain after this terrorist attack, only pain. I don’t know what happened, what is going on now.”

Sri Lanka’s 22 million people include minority Christians, Muslims and Hindus. Until now, Christians had largely managed to avoid the worst of the island’s conflict and communal tensions.

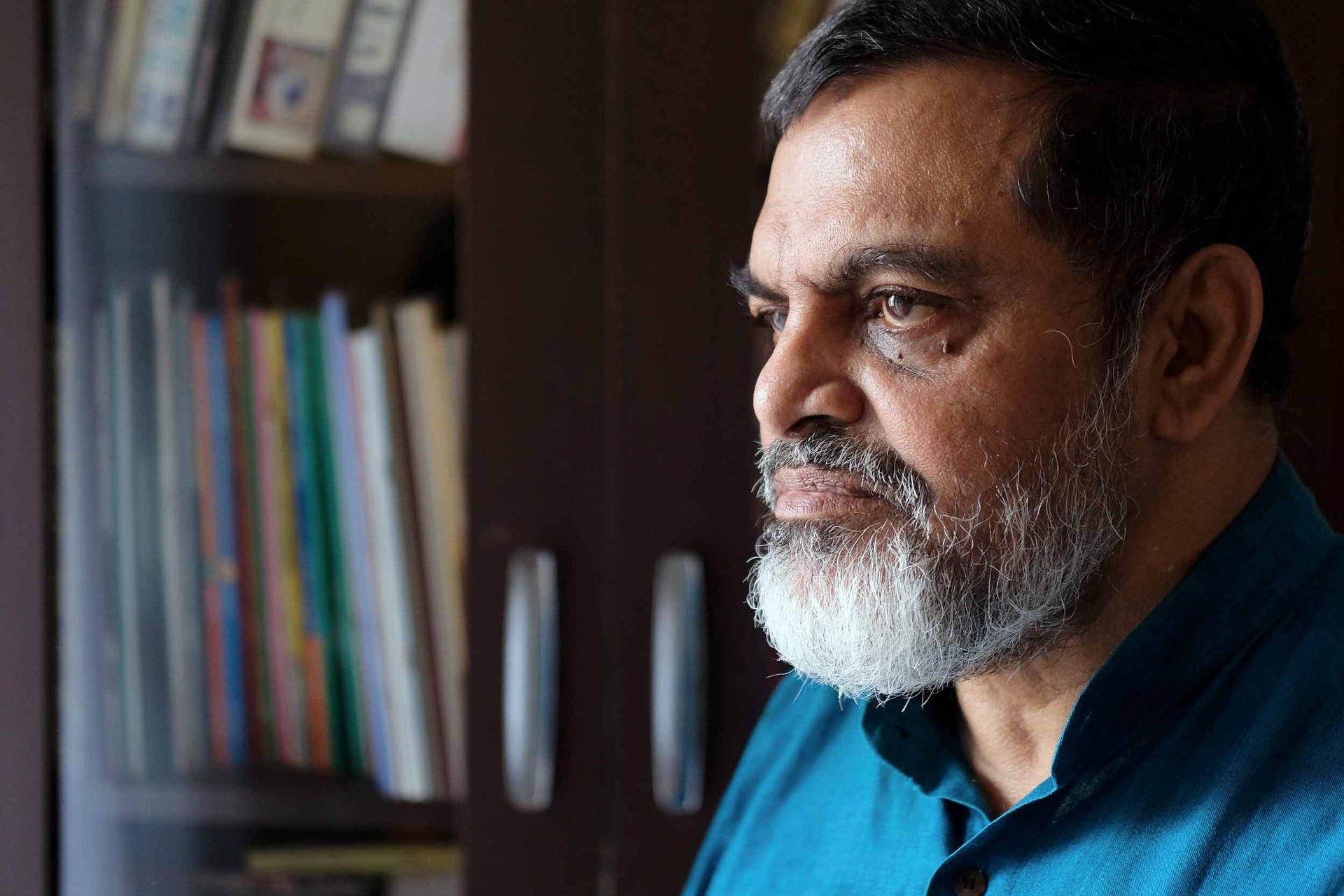

Javid Yusuf is a lawyer who works in human rights and peace and conflict resolution. He’s Muslim, as well.

“From the time of the ancient kings, Sri Lanka has been in my view a model of co-existence of harmony for centuries — Buddhist, Sinhalese, Muslims,” Yusuf said. “Unfortunately, after independence, we had a war; a lot of innocent people were killed.”

Related: Sri Lanka mourns with mass funerals

For nearly 30 years, there was a brutal civil war in Sri Lanka. But it was an ethnic conflict, not a religious one.

“The armed conflict ended in 2009,” Yusuf said. “Unfortunately, since 2012, there has been targeting of Muslims by extremists.”

A mob of Buddhist extremists attacked a mosque in 2013. The Buddhist extremists espoused a nationalist ideology, targeting Muslim and Christian Sri Lankans.

“They started developing stories and various myths that put insecurity in the minds of the ordinary Buddhist people,” Yusuf said.

Groups made unfounded accusations, accusing people of spraying women’s clothes with some kind of anti-fertility chemical.

“That’s the sort of fear psychosis they built,” Yusuf said.

Related: Who are Sri Lanka’s Christians?

And over the years, the rumors moved from hate speech and flared up into real violence. Towns have erupted into riots, with Sinhalese Buddhist mobs attacking Muslim businesses, houses and mosques, throwing stones and assaulting. This happened in 2014 and in 2018.

Bhavani Fonseka, a researcher at the CPA, says the government has not done enough for Muslim or Christian minorities.

“The fact that the government was not able to arrest, detain and prosecute perpetrators of religious violence is the reason why there has been impunity and that people have been able to continue these hate speech and attacks,” Fonseka said.

This has allowed Buddhist nationalist extremists to spread their ideology, hate speech and acts of violence, with little concern that they would be held to account.

When the Easter Sunday bombings happened, religious tensions in Sri Lanka were already high. Religious and political leaders — at least at the higher levels — have been careful not to set off the kind of vengeful violence they’ve seen in the past.

Sri Lankan authorities asked mosques to avoid Friday prayers, citing threats of additional bombings. Most mosques in Colombo heeded the warning.

Dawatagaha mosque in Colombo has decided to continue with prayers. Police and soldiers have been stationed outside the mosque.

According to Sri Lankan security agencies, the same group that perpetrated the attacks on Easter Sunday have also threatened this Sufi shrine.

“The reason we are holding prayers — that is our normal routine. We will have our prayers.”

“The reason we are holding prayers — that is our normal routine. We will have our prayers,” said Reyyaz Salley, the chairman of the mosque. “Along with our prayer for the victims who were killed during the bombing.”

The danger that the anti-Muslim violence will emerge is putting the city and authorities on alert.

“The real fear is that those who may want to seek revenge or may be very hurt, they may actually be very sad about the loss of their dear ones, may be used by these spoiler elements,” Yusuf explained. “You wind them up and get them to take the law into their own hands. That is the danger.”

Yusuf says that to prevent violence from spiraling, the Sri Lankan authorities have to implement to rule of law for all forms of religious extremism, whether Buddhist or Muslim.

“Small groups are not representative of Muslims, just like the small extremist groups are not representative of Buddhists,” Yusuf said. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s very easy to eliminate this group. It doesn’t have any support in the Muslim community. They don’t have a cause and what they are doing is totally abhorrent to civilized life.

The attacks are a setback for religious tensions in Sri Lanka.

“Hate speech has to be prevented because it has a way of distorting people’s minds, and you don’t know until they do something drastic.”

Reuters contributed to this report.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?