How to avoid accidentally becoming a Russian agent

Russia’s calling, but will you answer?

American citizens are unwittingly becoming Russian agents. That’s an unavoidable conclusion of Robert Mueller’s report on his investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election, and an important problem that requires a change in thinking about how people interact on social media. Old adages like “Don’t talk to strangers” don’t really apply in a hyperconnected world. A more accurate replacement is perhaps even more worrying, though: “If you talk to strangers online, assume they are spies until proven otherwise.”

Facebook estimated that 126 million Americans saw one of more than 3,500 Russian-purchased ads on its site. Twitter identified nearly 40,000 Russia-linked accounts that issued 1.5 million tweets, which were viewed a total of 288 million times. As a social media researcher and educator, this shows the scale of people’s exposure to state propaganda and the potential to influence public opinion. But that’s not the really bad news.

Related: The trolls are winning, says Russian troll hunter

According to the Mueller report, some US citizens even helped Russian government agents organize real-life events, aiding the propaganda campaign, possibly without knowing that’s what they were doing. There’s a whole section of the report called “Targeting and Recruitment of US Persons,” detailing how Russian agents approached people through direct messages on social media, as part of their efforts to sow discord and division in order to influence the 2016 US presidential election.

Mueller doesn’t say why these people let themselves be manipulated into participating. But this Russian victory, the co-opting of Americans against their own democratic processes, happened because the Russian government used old-school influence techniques on new social media platforms. Online predators with harmful agendas often use the same tricks, so learn to protect yourself.

Cooperate cautiously

Mainly, the Russians exploited what is called the drive to cooperate, an ingrained part of human nature that encourages people to work with others. It’s why you stop when you see someone stumble or drop something, or why you hold a door for a person carrying a lot of bags.

This human trait may have been better suited for times when people didn’t interact so much online with strangers — but rather a world where people used to interact primarily in real life with family, friends, neighbors, colleagues and classmates. Now, though, online interactions link people across the world through targeted advertising, specific search results, social media hashtags and corporate algorithms that suggest who else a person should connect with. These connections may seem as strong as in-person ones, but they carry much more risk for exploitation of human kindness and the need for belonging.

Related: Russian leaders literally cheer Trump’s victory

Generally speaking, social media accounts aren’t verified, which is a means of authenticating that an online account matches the identity of an actual person or organization in real life. Accounts are often anonymous, and it’s very easy and common for people to set up fake profiles that look like a real person. It is difficult to know for certain whom you’re interacting with or what they actually want out of your connection.

Thankfully, research has shown that people have defense mechanisms to avoid deception or what platforms have dubbed “inauthentic behavior.” Americans being targeted by Russians aren’t just sitting ducks — they have innate skills, if they remember to use them.

Reciprocate thoughtfully

Research on influence and its abuse shows how persuasion works and focuses on principles such as reciprocity — the act of returning favors and things like gifts for mutual benefit. This can be a small gesture, like friends taking turns buying drinks for each other. Online, it could be even smaller: Seeing someone share your post or respond to a comment you made can cause you to want to reply or like the post on their page.

Related: A guide to Russian ‘demotivator’ memes

To avoid being duped, check things out before you reciprocate. If you and another person in an online group are interacting in public view — sharing posts and making and liking comments — it’s probably fine. But if they then send you a direct message asking for a favor or to run an errand, keep your wits about you. You still have no idea who they are, what they do for work, what their name might be or even what country they live in.

Be especially cautious if they, for instance, ask you to wear a Santa Claus suit and a mask of Donald Trump’s face around your city. At least one American did this, according to the Mueller report. Consider Skyping them first, or seeing if they can speak to you without the aid of Google Translate or if their voice matches the gender they state on their profile.

Join forces skeptically

The Russian government also targeted close-knit communities with strong senses of shared identity, which scholars call “oneness.” They created online groups and pages that pretended to support and participate in the Black Lives Matter movement and the LGBTQ communities.

It’s clear that any identity-based online group could prove an easy target, so be careful when joining and affiliating with them, especially if you do not personally know the organizers in real life.

There are so many different situations where influence techniques could exploit aspects of human nature that it’s impossible to outline all the potential scenarios.

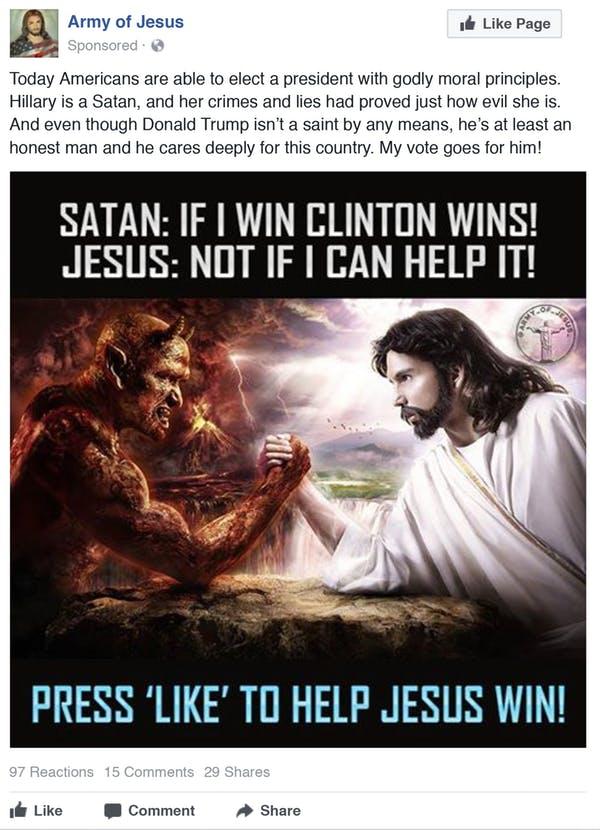

In his book “Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion,” psychologist Robert Cialdini offers a general rule to help defend against being swept into an influence campaign: Be on guard if you have a feeling of liking a contact more quickly, or more deeply, than you would have expected. Simply put, trust warnings from your gut if you’re starting to notice things are moving really quickly with someone you barely know. That’s especially true if this is an online friend, and even more so if the person regularly posts images of identity-based memes (known as memeplexes), like bald eagles (patriotism memeplex), rainbows (LGBTQ memeplex) or Jesus (Christian memeplex).

In an age where governments sow global political instability by exploiting social media and interpersonal trust, it’s more important than ever to be skeptical of people you connect with — not only online, but in line at Starbucks.![]()

Jennifer Grygiel is an assistant professor of communications (social media) & magazine at Syracuse University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!