US government to Filipino seasonal workers: No visas this year

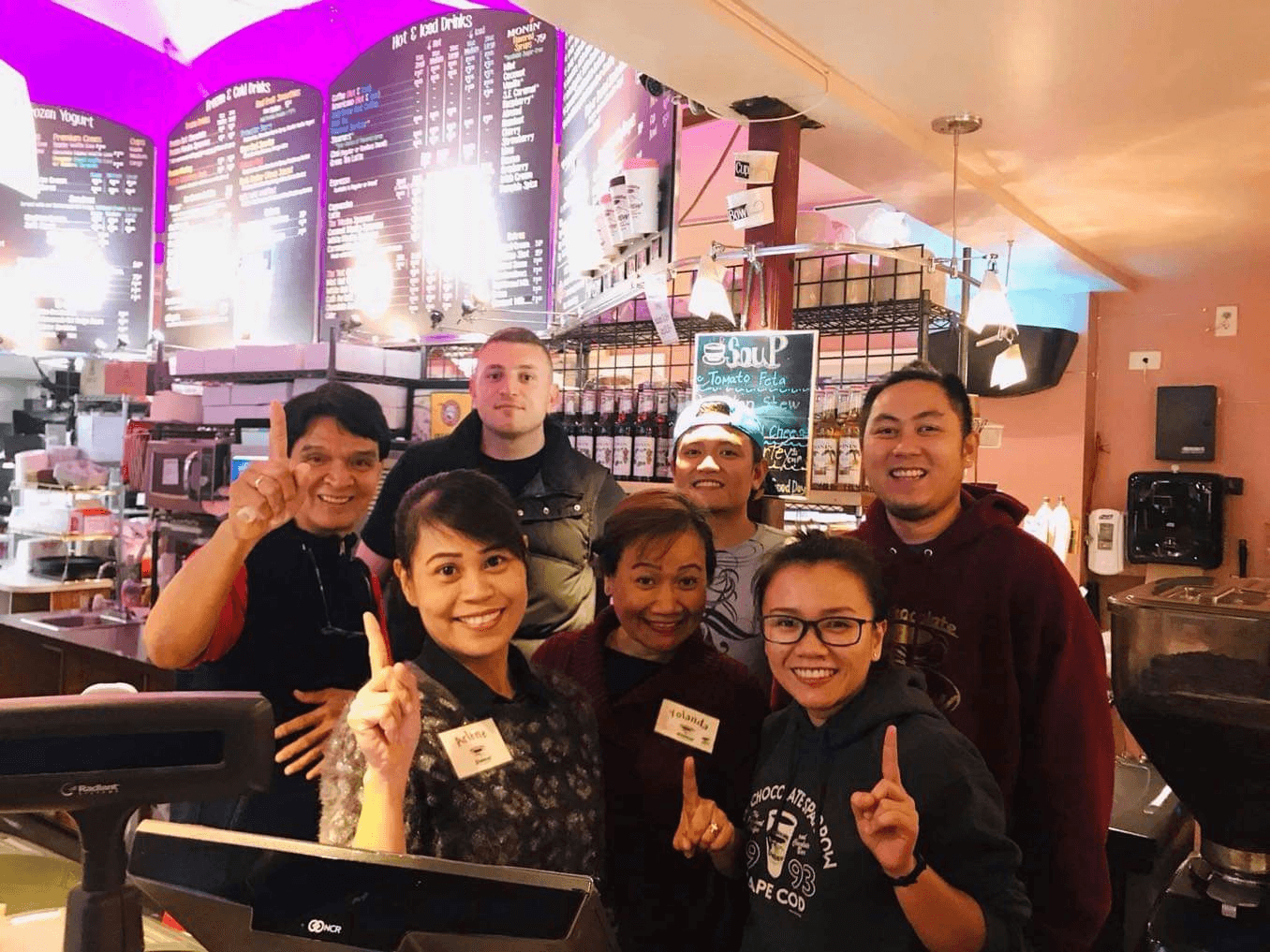

Rayben Tamayo stands in front of the ice cream counter for his summer employer, the Hot Chocolate Sparrow on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The owners put up a Philippine flag to honor their many seasonal summer employees.

For years, the Tamayo family has traveled from their home in the Philippines to their summer jobs at the Hot Chocolate Sparrow, a family-run coffee and dessert shop in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. They’re among the tens of thousands of workers who come from overseas on temporary, non-immigrant H-2B visas that allow them to work for up to six months at a stretch.

This year, however, they may not make it to Cape Cod. The Trump administration has said it will ban seasonal workers from the Philippines starting this year. It’s part of a broader effort to restrict US entry for foreign workers and push employers to hire Americans instead. And the Tamayos — along with their longtime employer, shop owner Perry Sparrow — are caught in the middle.

Sparrow is working with immigration lawyers and the Philippine Embassy to try to get visas for the family. The clock is ticking: The Tamayos are currently working as housekeepers at a Vermont ski resort on separate seasonal H-2B visas, which expire in less than a month. After that, the ban means they’ll have to leave the US and may not be allowed to return as workers.

The mother, Yolanda Tamayo, is making an appeal.

“To the United States of America President, honorable Donald Trump, please give us a chance to renew our H-2B visas. We did not violate any rules and regulations,” she said. “Please help us to go back to our summer employer.”

Come summer, the population of Cape Cod nearly quadruples with tourists and summer residents. At the Hot Chocolate Sparrow, which is located in Orleans, a small city on the Cape, lines stretch long as people wait for coffee, sandwiches, and ice cream.

And each year, the shops and restaurants in seasonal vacation spots such as Cape Cod — or the Outer Banks of North Carolina or Mackinac Island in Michigan — rely on foreign workers on H-2B visas to handle the influx of business. Filipinos comprise one of the biggest groups of H-2B visa holders. Trump also relies on H-2B workers to cook and serve food at Mar-a-Lago, his private club in Palm Beach, Florida.

Perry Sparrow said he first tries to hire American citizens for the summertime surge.

“The majority of our workers are American, but there’s just not enough,” Sparrow said. “You have 50-something restaurants in Orleans alone, and they all need workers.”

If Sparrow can first prove that he can’t hire Americans, he may bring in foreign workers on H-2B visas. He says that, frankly, he’d prefer Americans: It costs him a lot to pay for international flights and visa fees for his overseas workers. But the Tamayos are some of his most reliable workers.

“They fly back — the first day they land, they come back to work,” Perry said in an interview last year when he, along with thousands of other businesses, were struggling with a shortage of seasonal visas issued by the US government. “They pick right up where they left off. They know the inventory where everything goes, where they’re supposed to put things away. They’re valuable workers from day No. 1 when they come back.”

Back then, Sparrow was anxiously waiting to see if he’d win what’s called the worker visa “lottery,” under which businesses are randomly chosen to be able to hire seasonal H-2B workers. The Department of Homeland Security has the discretion to raise the cap of 66,000 H-2B workers per fiscal year. But in the past two years, it’s added a layer of screening — which has held up extra visas for months, when it’s too late for businesses that need help for the season.

“It’s a tremendous amount of stress,” he said.

This year, Sparrow’s stress is through the roof: In January, the Department of Homeland Security added another complication when it said Filipinos are no longer eligible for H-2B visas. It blamed Filipinos’ 40 percent overstay rate — high compared to other nationalities. So now, Sparrow is looking at a future without the Tamayos.

“You just feel kind of helpless. Business aside, it’s just unfair for them to lose out on an opportunity when they’ve done everything by the book. I mean, it’s more than just losing workers. All the customers know them here. It’s like losing part of your family.”

“You just feel kind of helpless,” Sparrow said recently. “Business aside, it’s just unfair for them to lose out on an opportunity when they’ve done everything by the book. I mean, it’s more than just losing workers. All the customers know them here. It’s like losing part of your family.”

That feeling is mutual.

“I really, really like to work there because they are really great. They treat us like a family member. They don’t treat us only like an employee,” said Rayben, Yolanda’s son, who has worked at the Hot Chocolate Sparrow for six summers.

Rayben is currently staying in a small apartment in Vermont, along with his wife, parents, sister and brother-in-law. He said he was shocked to hear Filipinos — along with workers from Ethiopia and the Dominican Republic — are now barred from getting H-2B visas.

“I feel really sad about it, because I think it’s really unfair, being a hardworking person,” he said. “They need to realize that Filipino people, they are here just to work and not to be doing illegal things.”

But in addition to overstays, DHS says Filipinos are using the H-2B visas as a cover for human trafficking. DHS officials declined an interview request with The World.

Yolanda Tamayo said she accepts the government’s trafficking claims: “We have to respect the decisions of the Department of Homeland Security.”

She said the people involved in illegal activity should be deported, but that her family shouldn’t be punished and denied their visas, too. “We are trying our best to strictly not violate any immigration law or US government law,” she said. “Maybe it’s God’s plan.”

But DHS hasn’t provided more detail about human trafficking from the Philippines.

“Who are these people involved? And where are they?” Yolanda Tamayo asked. “But we haven’t seen any list of these people involved.”

To some, the plan to ban Filipinos is simply unfair.

“If you’re going to punish an entire country, and the workers who want to come here to make a better life for themselves, I think you’re punishing the wrong group,” said Daniel Costa, director of immigration law and policy research with the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, DC. “You’re punishing workers from a country because previous workers were trafficked and victimized. The right response is to crack down on traffickers and to better regulate employers and the recruiters that use H-2B, and ban the recruiters and employers that violate labor and immigration laws rather than issue blanket bans on entire countries.”

Costa said the H-2B visa has a long history of worker exploitation, and structural flaws in the program could be a reason some Filipinos have overstayed.

“If they had to flee from an abusive employer, they probably still need to work to pay off the debts that they owe to recruiters,” he said.

Seasonal visa workers are tied to their employers: If they’re caught in a bad situation, they can’t just pick up and switch jobs — legally, that is. And a path to residency in the form of employer-sponsored green cards are very difficult to get for lower-skilled seasonal workers, the kind who tend to use H-2B visas.

So families like the Tamayos are stuck working within the H-2B visa system. Yolanda Tamayo has been going back and forth from the Philippines to work seasonal jobs in New England for 13 years. Her son, Rayben, says that when he was younger and living in the Philippines, he’d miss his mom when she went to work in the US.

“I graduated high school, college — she’s not with us, only my dad. And it’s hard for us,” Rayben Tamayo said.

Now he’s doing the same thing his mom did, splitting his life between the Philippines and the US. But he said the sacrifice is worth it. When he graduated college in the Philippines a few years back, jobs there were scarce.

“My first job ever in my life is being a janitor. It’s really hard. It’s in the mall. Per day, I made only 480 [Philippine] pesos — it’s only $10 per day,” Rayben Tamayo said.

In the US, he earns $11 per hour — enough to send some money back home to relatives.

Sparrow is appealing for an exception to the visa ban on the Tamayos’ behalf, since the family is already in the US and in good standing. But their future is uncertain.

“I seem to be getting different answers. It’s like trying to herd cats. I just don’t really know,” Sparrow said. “On top of all that, I’ve got a business to run every day.”

A DHS spokesperson said the agency will evaluate petitioners on a case-by-case basis, even if they are from the Philippines. The Tamayos have until mid-April to get an answer.

If not, they’ll have to head back to the Philippines, and Sparrow will have to figure out how to find enough workers to keep his summertime business running.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?