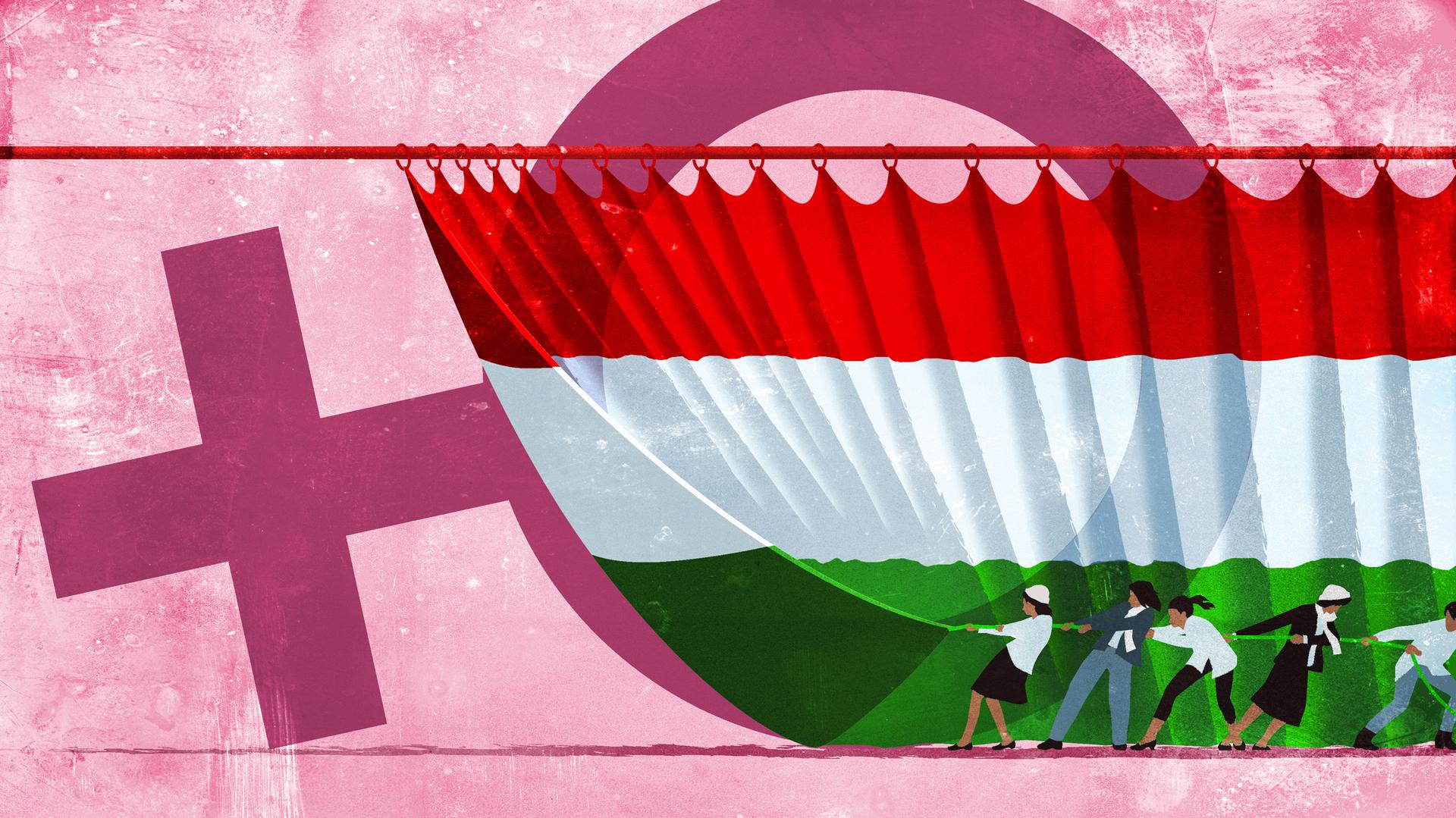

These women are challenging Hungary’s ‘men in suits’ politics

Anna Donáth spent her first night in police custody in December.

Her phone and bag were missing, and she worried no one knew where she was.

Donáth was arrested as she lead protestors through the streets of Budapest, who had gathered in opposition to a new overtime bill passed by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his far-right government.

But as Donáth, the vice-president of Hungary’s new political party Momentum, sat in the police station in the middle of the night, she heard something. It was the sound of chanting.

“‘Let’s free Anna, let’s free Anna’, they were shouting,” Donáth, 31, says. “There were a couple of hundred people there.”

After hours sitting in a police cell, she realized she had nothing to fear.

“It was phenomenal to suddenly know there was this community behind me,” she says.

Related: In Orbán’s Hungary, refugees are unwelcome — so are those who try to help

The overtime bill, dubbed the “slave law” by critics brought thousands out onto the streets. Budapest has seen its share of mass demonstrations but opposition parties rarely unite in protest. So when eight female politicians from all the opposition parties took to the stage, united against a government ruling, people took notice. In Hungary this was unprecedented.

Their hope is that together they can build a credible opposition to Orbán and his powerful Fidesz party.

But the number of women in Hungary’s parliament is small and Orbán’s popularity seems unchanged after almost nine years in power.

The rallies began in furious opposition to a change in Hungary’s overtime laws, which said that workers could be forced to work 400 hours of overtime — while giving employers up to three years to compensate employees. Legislators said the bill was a response to a labor crisis.

But as the protests grew, the message changed from anti-labor laws to broadly anti-regime.

A photo of Anna Donáth holding a purple flare aloft during one of the rallies has become a symbol of the protest movement. She, along with other female politicians, trade unionists and young students, hopes to create a credible protest movement against Orbán.

But Donáth said she understands the challenges women face getting their voices heard.

“The media here — that is, the pro-government media — portray politics as something that is for men in suits. They believe women should stay home and take care of the children.

“Hungary has a really macho culture,” Donáth says. “The media here — that is, the pro-government media — portray politics as something that is for men in suits. They believe women should stay home and take care of the children.”

Related: As Orbán rises, Hungary’s free press falls

Hungary does not have a good reputation for promoting women in political life. The Global Gender Gap Report noted in 2018 that Hungary was one of the lowest performing countries worldwide with regard to closing the political empowerment gender gap. Among European Union countries, it has the lowest number of female members of parliament: just 12 percent. Compare that to Iceland, where women make up almost half the numbers in parliament at 48 percent, or to Spain, where for the first time since the country became a democracy, there are more women than men in the cabinet.

Orbán does not see women’s low representation in government as a problem. In 2015, when asked why there were no women in his cabinet, Orbán said few women could deal with the stress of politics. Today, Andrea Bártfai-Mager is the one female minister in the cabinet.

Katalin Novák is vice president of Fidesz, the ruling party and a Minister of State for Family and Youth Affairs. She says Hungary’s poor record for promoting women in politics is because of the country’s recent history.

“We haven’t had a very long history in modern democracy,” she says. “We have only had free elections since 1990.”

Novák is dismissive of criticism of Orbán’s comments about women not being up to the challenge of politics.

“I don’t think that every man or every woman is eligible for [political] life.”

“It is a tough life for women, and for men as well,” Novák says. “I don’t think that every man or every woman is eligible for this life.”

Another leading figure of the recent anti-government protests is Bernadett Szél, a member of parliament. As one of only 14 female opposition MPs out of 199 total seats in parliament, Szél says she believes all political parties are to blame for the dearth of female parliamentarians.

“In little villages, there are more and more women working in local politics, but at the top, you hardly see any women,” she says. “The parties fail to promote them.”

“The parties fail to promote them.”

Szél recognizes that her position in politics is relatively unusual in Hungary and gives credit to her husband for making it possible.

“I have a wonderful man and at home, I’m given a lot of help,” she says. “It is very difficult to have your private life and professional life match each other.”

It’s not just in politics where Hungarian women struggle. The model in Hungary leans squarely towards male breadwinner and female caretaker.

Orbán announced this week that women who have four or more children will be exempt from paying income tax. The measure is aimed at encouraging Hungarian women to have more children so the country does not have to depend on immigration to grow its declining population.

But the effort also re-emphasizes the woman’s role as homemaker and mother.

Anikó Gregor, an assistant professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences in Budapest’s Eötvös Loránd University, says Hungarian women face “dual responsibilities.”

“Their primary responsibility is taking care of children and elderly people — and then being a worker contributing to GDP,” she says.

And there can be harsh consequences for women who do speak out.

Blanka Nagy, a 19-year-old high school student, was vilified by pro-government newspapers when she made a speech criticizing Orbán’s party at a December rally in Kecskemét. Nagy used a number of expletives in her speech about the Fidesz party. One news site, Ripost, alleged that she was failing at school and suggested she regularly watches sex tapes. She denies both statements.

Related: What does Hungary’s crackdown on free media mean for the rest of the world?

Nagy says she is not perturbed by the backlash, although admits the critical comments on her Facebook page made her a little uncomfortable — but she says she feels “no fear” at the thought of continuing to speak out.

As they challenge a male-dominated culture and weather attacks by those who disagree with them, Hungary’s female politicians say they face self-doubt too.

“I have lots of doubts about whether I’m doing well, whether I should be doing this,” Donáth says. “Then I think that’s a typical female thing to believe. Men would just jump in and do it.”

Szél recognizes the sentiment, too.

“Many women ask themselves, ‘Am I good enough to run for office?’”

Yes, they are, she says.

“So, I started a program where I invite women into parliament so they can see for themselves the possibility of a life in politics.”

It’s three more years until Hungary’s next general election, but local elections are scheduled for later this year. Szél and Donáth hope their efforts will see more Hungarian women on the ballot.