This teen migrated to the US border to escape gangs. He hopes to join his mom in the US.

Vladi, center, is from El Salvador. He says the gangs try to recruit you when you turn 14 or 15. He’s 15. He says instead of joining a gang, he joined the migrant “caravan” headed toward the United States.

In late November, reporter Monica Campbell headed to Tijuana, Mexico, to meet a teenager from El Salvador. He had arrived there recently, along with his grandmother, who accompanied him as far as Tijuana. They had joined the large group of migrants who made headlines that fall traveling north from Central America through Mexico.

But by late November, Vladi, 15, was on his own. His grandmother needed to return to El Salvador, and Vladi remained at a small youth shelter for other unaccompanied migrants like him. Many were hoping to seek asylum in the United States. So was Vladi.

There was also a loved one waiting for him on the other side of the border: his mom. Fearing gang threats, Verónica Aguilar left El Salvador in 2017 and presented herself at the US-Mexico border to seek asylum. After months in immigration detention in California, Aguilar then followed her original plan — to send for Vladi and have him join her and begin a safer life together in the United States.

In “The Boy in the Caravan,” an episode of The Frontline Dispatch that was produced in collaboration with PRI’s The World, we follow Vladi’s story as he tries to enter the United States at a time when the doors are closing at the border. We also go beyond the border to report on the immediate challenges young people — and their loved ones — face if they do manage to enter the US. Listen to the full podcast episode here:

Shortly after arriving in Tijuana in November, Vladi, center, stayed at a shelter for unaccompanied migrant youth located off a busy street about 10 minutes from the border. Youth at the shelter must follow certain rules: no smoking, no drinking, make curfew. This part of Mexico can be unsafe.

In December 2018, not long after Vladi had left, two teenagers from Honduras staying at the shelter were found murdered not far away. Their bodies were discovered on the side of the road.

Related: After two boys’ murders, migrants and advocates fear new ‘remain in Mexico’ policy

Tijuana can be dangerous, but El Salvador wasn’t safe, either. Vladi says he was threatened by the gangs, feeling pressured to join them.

“Once you turn 14 or 15, it’s the risk you run,” he said.

As he waited for his moment to try and enter the US, with the help of lawyers, he killed time at the shelter on his phone. He’s hooked on the “Clash of Clans” video game and enjoys watching Japanese anime. When asked how he pictures life in the United States, Vladi says he wants to go to high school and study.

“I have to get good grades, or my mom will take away my cell,” he said.

While Vladi waits in a shelter in Mexico, his mother waits for him in California. A couple took her in after she was released from detention in June 2018.

She says that Vladi’s dad was a main reason she fled El Salvador. He’s in prison for murder and was in a gang. When she tried to cut off ties with him, he told her she was being disloyal and keeping his son from him. Threats followed. One time, she was walking home, and a man stopped her and said, “Put out your hand.” He put three bullets in her palm and said they would be used to kill her.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, Aguilar built a life of her own and made ends meet. She worked at a supermarket and sewed Lycra tights in a factory. She also enjoyed lifting weights and competed at powerlifting events.

Life is so different now in California, especially without Vladi. But she says that she always meant to send for him once she’d figured out a place for them to live. She wanted to pave the way to the United States first — and she considered the migrant caravan a safer way to bring Vladi to the US, not a smuggler. Yet, she worried about him as he traveled north to the US border, talking to him four or five times a day.

“If he didn’t have a signal, it was horrible because I just thought, ‘My God, why isn’t he answering?’” she said. She tried not to panic, but was especially anxious when Vladi crossed into Mexico from Guatemala on a raft made of tires and wood.

As she waits for Vladi, Aguilar said she can “get so worried, there’s a pain in my chest wondering where he’s been, how he’s been, whether he’s eaten.” But she added, “I have faith in God it’ll all be fine. I just have to wait.”

As she waits for Vladi, Aguilar is also building a support network in California, including people from pro-immigrant rights groups who connect migrants with legal services as they approach the US-Mexico border and reach the US. She is also sharing her story as just one family’s experience among the thousands of migrants who have arrived at the border in recent months.

Aguilar says she is proud of the life she is building in Pinole, but wants her son with her. She feels especially bad she’s missed his 15th birthday and teases him on the phone that she’ll make him a pink cake when he arrives — like the cake someone would make for a 15-year-old girl celebrating a quinceañera.

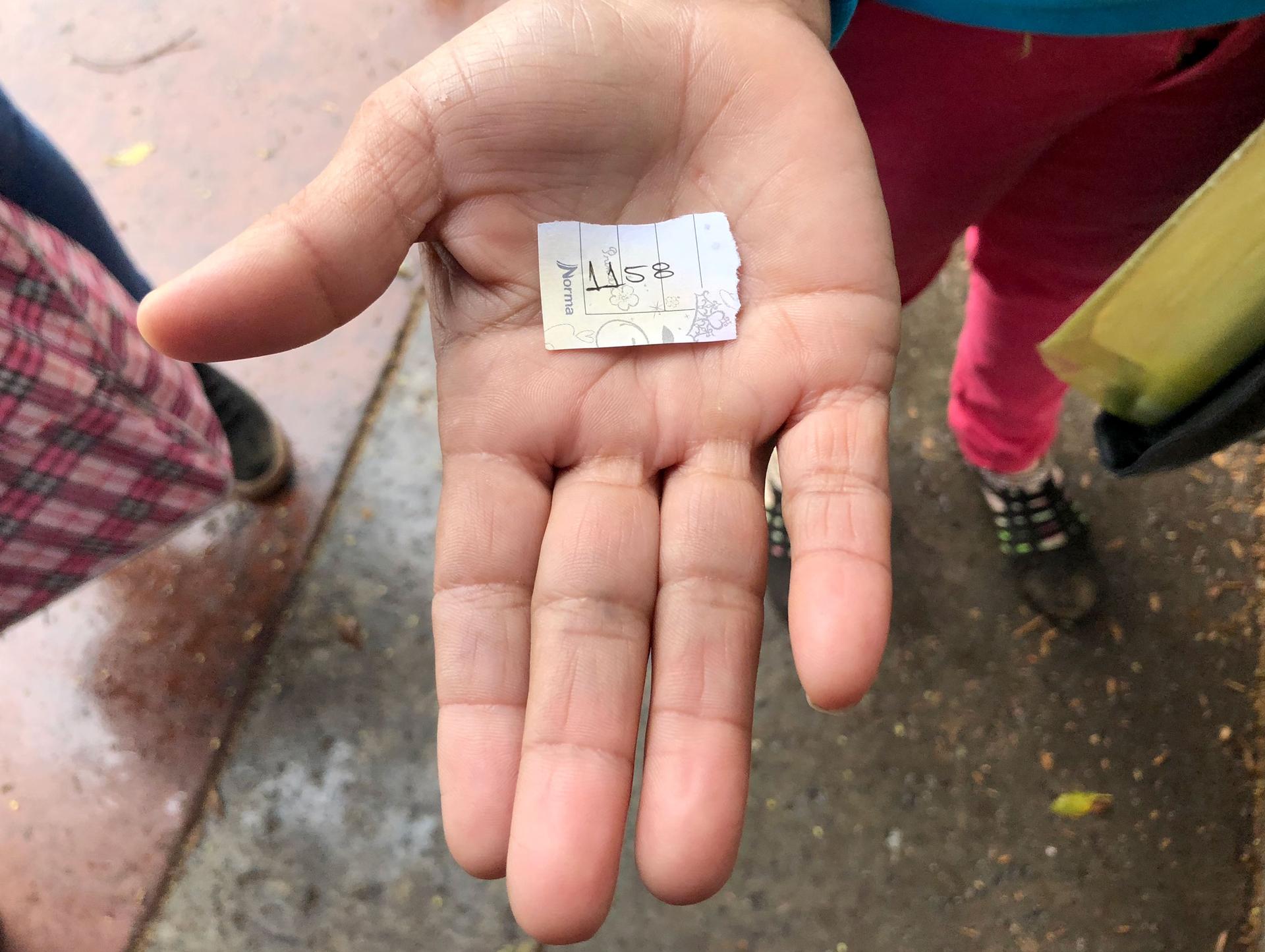

An asylum-seeker in Tijuana shows the number she was given that corresponds with her name in a notebook managed by Mexican officials in Tijuana. It’s a way of creating a line of sorts for the thousands of migrants amassed, waiting to cross. If your number is called, you can go up to the border to US officials and ask for asylum.

Vladi approached the US-Mexico border on Dec. 1 to ask for asylum. He was accompanied by US immigration lawyers.

The lawyers think border agents are profiling migrants, so they made sure Vladi would blend in — like a Mexican teenager going to the US to go shopping or something.

“And so much to his [Vladi’s] dismay, we found some khaki pants and a button-down, plaid shirt for him,” said Lindsay Toczylowski, one of the lawyers with Vladi at the time. “I had to physically tuck the shirt in and hike his pants up really high and put a belt on. I think he felt like he was in a nerd costume.”

When they got to the port of entry, the lawyers told the Customs and Border Protection officers how they were with asylum-seekers. A CPB supervisor came out and said: “Sorry, no room.”

They were getting turned away.

“They said they didn’t have the facilities to hold anyone,” Toczylowski said.

The lawyers started going back and forth trying to persuade the CBP officers to let Vladi in. Everyone waited outside in the cold and the wind for hours.

Then, someone showed up: a Democratic member of Congress from Washington state — Rep. Pramila Jayapal. She was in Tijuana touring the shelters and wanted to see the ports of entry up close.

“I stepped forward, and I started asking these questions of the border patrol agents,” Jayapal said. “They got very irritated, I think, that I was asking questions. I had not identified myself as a Congress member yet, because I wanted to see what happens if you’re not a member of Congress.”

She started pressing the officers, insisting.

“Once I did identify myself as a member of Congress and really pushed … the border patrol agent said, ‘We will take the two unaccompanied minors.'”

Vladi and another unaccompanied minor were allowed in.

Both the Department of Homeland Security and Customs and Border Protection declined interview requests.

Scenes like this are playing out a lot at the border right now — kids with lawyers, nerd costumes, trying to get into the US one by one, like special packages with lots of handlers.

After being kept in a holding cell at the California border for several days, Vladi was transferred to a large shelter for unaccompanied minors in Homestead, Florida, near Miami. He was allowed to make two, 10-minute calls a week.

He’s joining an estimated 10,000-some young migrants in federal custody, waiting for the government to decide what to do with them.

“He’s tired, but fine,” Aguilar said. He’s not being held at the border anymore. Aguilar’s been there, in the cells that migrants call hieleras — iceboxes.

But a new chapter begins — another wait — to see when Vladi can leave Florida. Weeks go by, Christmas and the New Year, and Aguilar grows frustrated with how long her son has been in the shelter. She knows it can take awhile — the average stay is two months — but she doesn’t get why. “I don’t understand what’s happening,” she said. “I did the fingerprints. I’ve proved he’s my son.”

She knows the government has to follow protocol, but she feels left in the dark about the process.

During their calls, Aguilar asks Vladi if he’d like a soccer ball once he’s out. Yes, he says. Aguilar then tells Vladi about some soccer fields nearby. She wants to get him excited about things he can do here, so he has something to look forward to.

Aguilar is also impressed with how Vladi is handling being detained. She feels it’s a sign of him becoming more mature.

On another call, Vladi asks if his mom can visit. She sighs.

“I can’t,” she said. “I can’t afford it.”

They exchange I love yous, and Aguilar said, “When you’re back, I’ll get your 15th birthday cake. A pink one.”

Editor’s note: The day before we published this story, Verónica Aguilar was told that Vladi would be released and flown to Los Angeles this week.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?