Garbage collection in Syria is crucial to fighting ISIS

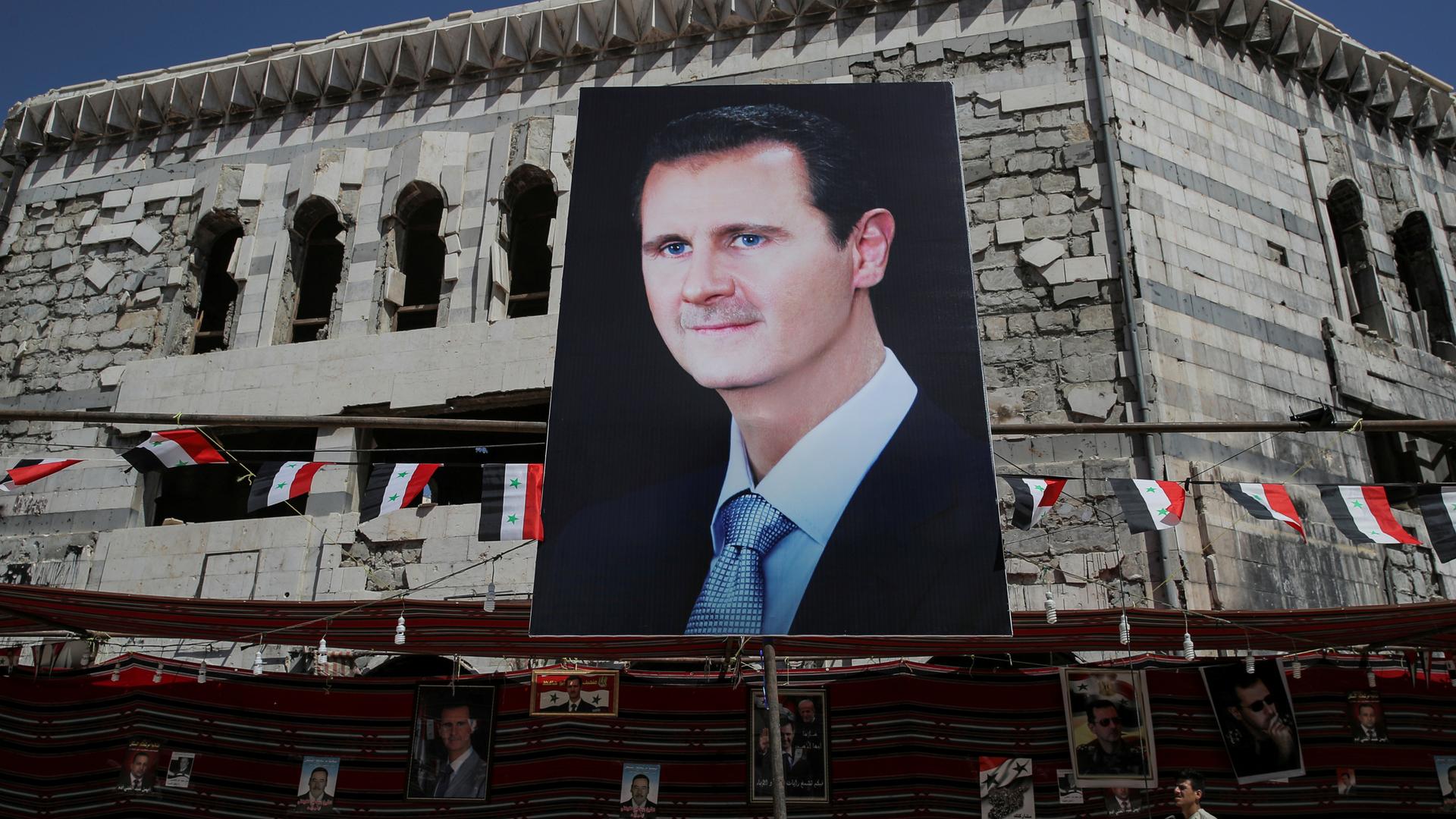

A huge banner depicts Syrian president Bashar al-Assad in Douma, outside Damascus, Syria, Sept. 17, 2018. A lack of basic civil services in war-torn countries like Syria often leaves a vacuum for militant groups like ISIS to take over essentially ungoverned spaces.

Just a few years ago, I was a diplomat working on the Turkish-Syrian border. My job was managing the US government team responsible for delivering aid to Syrian towns and cities loyal to the Syrian opposition.

These were towns that had turned against President Bashar al-Assad when the Arab Spring swept across the Middle East and Assad ordered his army to shoot peaceful civilians protesting against him.

Now I’m retired from the US Foreign Service and teaching international relations at the University of Washington in Seattle, where my students struggle to understand why the US never seems to learn from past mistakes in the conduct of our foreign affairs.

Given recent decisions and announcements by President Trump about withdrawing much of our aid and our troops from northern Syria while the civil war continues and ISIS still threatens, it’s a timely question.

Related: When the US pulls out of Syria, what happens to ISIS?

Stability and local services

To understand what’s at stake in Syria, it’s helpful to look at Iraq.

More than 15 years after the US invaded Iraq and eight years after the US said it was leaving the country, Iraq is unstable. Five thousand US soldiers remain in Iraq today, tasked with shoring up the still struggling Iraqi armed forces.

One of the reasons for the instability is the US decision in 2003 to dismiss nearly all leaders of the Iraqi civil service when it toppled dictator Saddam Hussein because they were members of Hussein’s Baath Party.

With much of the civil service gone, local services like water and electricity fell apart and essential public employees fled. That left a perfect vacuum for extremist groups like ISIS to exploit by taking control of essentially ungoverned territory. The US continues to pay the price for this avoidable decision today.

If the US cuts off support for communities inside Syria that oppose Bashar al-Assad and fly the Syrian opposition flag, and withdraws American troops from the fight against ISIS — as President Trump has announced — we will be making the same mistake again. We’ll be creating a vacuum our enemies can exploit.

Related: As US declares victory over ISIS, a withdrawal from Syria proves perilous

Keeping local officials on the job

The US has supported these communities since 2012. I directed the distribution of hundreds of millions of dollars in US government aid from 2012 until 2016, as head of the team known as the Syria Transition Assistance Response Team.

Syrian refugees will never go back home if their towns can’t offer the basic services they enjoyed before the war.

Our simple strategy was that when peace returns to Syria, key local officials would still be on the job, ready to reconnect their communities to the national systems that provided services before the war.

Thus would begin the long, difficult process of reuniting Syria.

The money and supplies my team and I delivered helped keep important local officials on the job so they wouldn’t give up and flee their country to seek refuge in Turkey, Lebanon or Jordan, like millions of others before them. These were experienced civilians who could keep the water and power on, manage the sewers and clean the streets.

We helped them with small stipends — a portion of their former salary — because the Syrian government had stopped paying them. And we provided equipment they needed to do their jobs: garbage trucks, generators, water tanks and fire trucks. We helped teachers, doctors and local police with small stipends, supplies and equipment, too.

Nothing was more satisfying for me than seeing videos of a new garbage truck that we sent from Turkey removing piles of garbage from the streets of Saraqib or one of the new ambulances we provided tending to innocent civilians injured in the latest barrel bombing in Aleppo.

It’s in everyone’s interest to keep civil service workers on the job, paid something and equipped. That will help put Syria back together again someday and deny ungoverned space for ISIS and other extremist groups. The last thing the US and countries in the region need is for Syria to disintegrate into warring regions, like Iraq and Libya today.

Related: Iraq gets on board with new rail service to Fallujah through former ISIS territory

International aid

Other countries joined the effort to rebuild Syria, notably the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark. Still more countries are contributing to an international fund based in Jordan that helps the same communities; my team cooperated closely with this effort.

Stopping this funding means jeopardizing Syria’s future at the worst possible time, just as the conflict appears to be coming to an end. I believe that reuniting the country should be the priority now.

Syria’s neighbors, especially Turkey, long supported the US approach because it kept Syrians in Syria, diminishing the flood of refugees to Turkey.

Of course, the Syrian government and its supporters, Russia and Iran, opposed our aid. The assistance we gave sustained communities that the government and its allies continue to bomb into submission and surrender, particularly in Idlib province.

But the aid President Trump cut, sometimes called stabilization assistance, goes to local civilian officials, working to help the sick and wounded and keep children in school.

An opening for ISIS

Similarly, withdrawing US troops sent to Syria to eliminate ISIS — when our own count suggests at least 1,000 ISIS fighters remain there — may serve short term political ends, but will likely come back to haunt the US and Syria’s neighbors.

President Trump may worry about the price tag for rebuilding Syria, once the war ends. He is right to be concerned. The cost will be enormous and arguably the US should not spend a dime.

The old adage — you broke it, you fix it — applies to the Syria conflict. I believe we should let Syria, Russia and Iran pay the billions it will take to fix what they broke — the infrastructure of bombed-out cities and towns.

The modest US investment in local communities that the White House cut off — $200 million, not billions — could have helped prevent the collapse of communities in the future.

Related: When the US pulls out of Syria, what happens to ISIS?

So, what do I tell my students in Seattle?

I remind them that they are our future leaders. I tell them that if we are not to repeat the mistakes of my generation, they should study and learn from history, and avoid short-term fixes to disentangle the US from future foreign interventions.

“Silver bullets” don’t work — and usually force us to return later, at a greater cost.![]()

Mark Ward is a lecturer at the University of Washington.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?