In Myanmar, underground poetry nights build bridges between Rohingya and Burmese writers

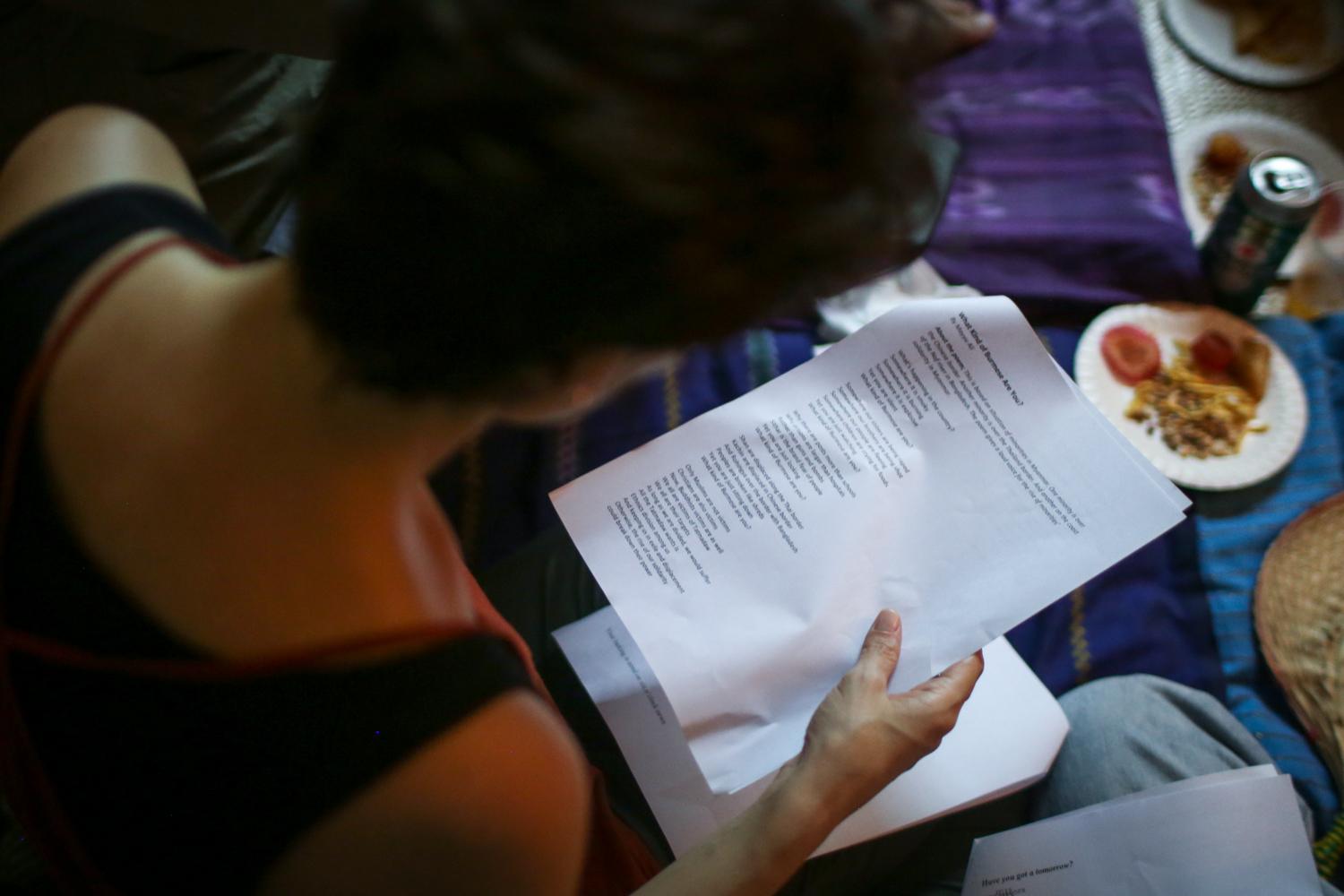

Maung Saungkha looks on as Rohingya poet Mayyu Ali reads his poem over a video call, projected on to the wall in a private home in downtown Yangon, Myanmar, Sept. 29, 2019.

In June this year, a small group of Myanmar residents crowded around a projector screen in an apartment loft in downtown Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city, to listen to poetry read via video call by Rohingya poet and refugee, Mayyu Ali, who was over 600 miles away in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

“Even when I live in the country where I was born/ I can’t name it as mine like you do./ Without identity,/ Just like an immigrant,” he said, reciting part of his poem, “That’s Me, a Rohingya,”while the audience listened, captivated.

“Even when I breathe the sky’s air/I’m not human like you are.”

“Even when I breathe the sky’s air/ I’m not human like you are.”

The first of three poetry readings over the summer and into the fall in Yangon, the events created space for Rohingya and Myanmar communities to share and exchange ideas in an otherwise deeply polarized society: Nearly two years earlier, the Myanmar military waged a brutal campaign against the Rohingya in Myanmar that drove over 740,000 of the persecuted Muslim minority into neighboring Bangladesh. Those who remain in Myanmar live in “urban ghettoes,” a UN official said this summer.

That campaign was the culmination of deep social and political tensions that have existed for decades in Myanmar, where the predominantly Buddhist country has long denied citizenship to the Rohingya along with education, healthcare, freedom of movement and other human rights.

The word Rohingya itself is taboo in Myanmar, where citizens pejoratively refer to Rohingya as “Bengalis,” implying their status as immigrants from Bangladesh.

“If you are based in another country outside of Myanmar, you can stand for the Rohingya easily. … But for [those of us in Myanmar], it’s very difficult and dangerous.”

The poetry readings offered a small beacon of hope at a time when the Rohingya in Bangladesh live in constant uncertainty. On Sept. 9, the Bangladesh Telecommunications Regulatory Commission “directed all telecommunication operators to shut down 3G and 4G services in the camps, according to Human Rights Watch, who also said high-speed service has been shut down since Sept. 10. Some 600,000 Rohingya people who remain in Myanmar continue to live in forced confinement to ghettos within Rakhine State, with no access to aid, telecommunications or basic services.

“If you are based in another country outside of Myanmar, you can stand for the Rohingya easily,” said poet and Myanmar resident, Maung Saungkha, who helped organize and also participated in the poetry event. “But for [those of us in Myanmar], it’s very difficult and dangerous.”

Maung Saungkha was jailed for six months in late 2015 for writing a poem, titled “Image,” which included the lines, “I have the president’s portrait tattooed on my penis/ How disgusted my wife is.” When a mutual friend told Maung Saungkha that Mayyu Ali wanted to read his poetry at the same event as him, it aligned with his interfaith and free speech activism.

“The Rohingya have always been fleeing and suffering from a lot of bad things. I never thought that they were writing poems,” Maung Saungkha said. “I am happy to be able to support [Rohingya] poets.”

The event’s participants and organizers were fully aware that they were doing something sensitive. In a country where even the word “Rohingya” is taboo, there was a risk that the audience would respond badly.

“Mayyu Ali said to me, ‘Please make sure that the audience is friendly,’ which in Yangon, is not easy,” said QL, an expatriate living in Yangon, who volunteered her apartment for the poetry event. “… I strictly vetted who was going to be invited to come, for [the poets’] peace of mind and safety but also for my own safety.”QL requested anonymity because she fears being targeted for hosting a Rohingya-friendly event.

On the evening of the event, after Maung Saungkha read his poems, Mayyu Ali appeared on a projector screen set up at one end of the room.

“First I greeted the audience with ‘mingalaba.’ … I saw there were some Burmese [people in the] audience and they greeted me, ‘mingalaba.’ I was amused and delighted by that, as I felt Burmese again, even though I am in a refugee camp.”

“First I greeted the audience with ‘mingalaba,’” said Mayyu Ali, referencing the standard greeting used between people in Myanmar. “I saw there were some Burmese [people in the] audience and they greeted me, ‘mingalaba.’ I was amused and delighted by that, as I felt Burmese again, even though I am in a refugee camp.”

For Hnin Yee Htun, who attended the event, hearing Mayyu Ali’s poetry reminded her of her own experiences. Her family fled Myanmar’s military regime in the 1980s and she spent her early years in a refugee camp on the Myanmar-Thai border.

“For me, it was quite emotional,” she said. “When I was a refugee I was quite little and I didn’t know that you could connect with the outside world. So, to be able to exchange stories so that we outside people get to see what they’re feeling … I’m glad he’s doing it.”

While the event was the first to bring together Rohingya and Myanmar poets, poetry has long played a role in Myanmar’s political history, Maung Saungkha said.

“In the colonial era, famous poets started writing about the [British] and why we need to fight them [for independence]. Poems were used to encourage and motivate people,” he said. “In the military era, poets were trying to talk about the real situation of Myanmar politics. But because of [the military junta] we could not talk about politics directly.”

The same indirect tactics are sometimes used in Myanmar today, where free speech remains under attack, as exemplified with the arrest of two Reuters journalists over their investigation into a massacre of Rohingya men.

Mayyu Ali, who published his work in Myanmar magazines under a pseudonym from 2009 to 2012, said he often used his poems to talk about issues faced by the Rohingya community.

“I started writing poetry because my writing is activism for me. I want to bring the attention of the international community toward the pain and suffering that Rohingya people have been facing: decades-long ethnic cleansing now that has the hallmarks of genocide,” said Mayyu Ali. “In my writing, I want my voice to be heard and to be representative of the suffering of my people.”

In the camps in Bangladesh, Mayyu Ali is a mentor to the next generation of young Rohingya poets, many of whom have limited access to education and other resources. Earlier this year, he launched Art Garden, a Facebook page where young Rohingya poets and artists can share their work.

“I get a lot of support from Mayyu Ali,” said Rohingya poet and refugee Anamal Hassan, who has published some of his poems through Art Garden. “It’s because of his love and support that I’m writing poems.”

And the number of budding Rohingya poets is continuing to grow, Mayyu Ali said.

“Now we have more than 150 Rohingya poets,” Mayyu Ali said. “Day by day, they have started writing poetry and the number of poets has been increasing. It’s a big achievement.”

But he faces an uphill battle to connect this growing community of refugee poets with a potential audience in Myanmar. Few other artists in Myanmar have created work or held events that include Rohingya, and influential Buddhist nationalists and government officials maintain that the marginalized community has no place in the country.

Yet Maung Saungkha and Mayyu Ali both said they have plans to continue holding poetry events in Yangon, including non-Rohingya poets from Rakhine state.

Some members of the Rakhine community assisted the military in driving the Rohingya from Myanmar, but as an ethnic minority, Myanmar’s military has also persecuted non-Rohingya living in Rakhine state, denying civilians access to humanitarian aid, arbitrarily detaining residents and cutting telecommunications without warning.

“We have been discussing and planning and thinking and moving forward and building trust with each other,” Mayyu Ali said, referring to Rakhine and Myanmar poets.

“We will write poetry about peace, harmony, reconciliation, and togetherness — not shooting and bad things — for inspiration to move forward and to bring both communities to see each other in love and in kindness.”