Pizza makers, video gamers, rockstars: Ukraine’s new parliament turns politics ‘upside down’

Rockstar and Golos political party leader Svyatoslav Vakarchuk speaks at his party’s electoral headquarters on election day, July 21.

No one imagined it would be a fair fight.

On July 21, veteran Ukrainian politician Vyacheslav Boguslayev competed with a 29-year-old former videogame journalist and current wedding photographer for a place in the Rada — Ukraine’s parliament.

Boguslayev’s opponent, Sergey Shtepa, was just 3 years old in 1993 when Boguslayev worked as an adviser to Ukraine’s first president, Leonid Kravchuk.

Related: Ukraine voters reject status quo in vote for ‘unprepared’ president

The two battled in Zaporozhye, the city where thousands of voters also work at Motor Sich, an aircraft engine manufacturer that Boguslayev has led for decades. An industrialist with deep pockets and even deeper connections, Boguslayev held a comfortable seat in the parliament and embodies Ukraine’s tendency to intertwine politics with business.

Related: Ukraine’s public broadcasters want a free press

It should not have been a fair fight and — in the end — it wasn’t: Shtepa trounced Boguslayev — who only got 44% of the vote in the 77th district — bringing the businessman’s 13-year tenure in parliament to a close.

According to an analysis by Opora, an election monitoring non-governmental organization, first-timers like Shtepa will comprise 80.4% of the next parliament — the highest figure since the country held its first parliamentary elections after breaking away from the Soviet Union in 1994.

Related: Spellcheck beware: Ukraine’s capital is #KyivNotKiev

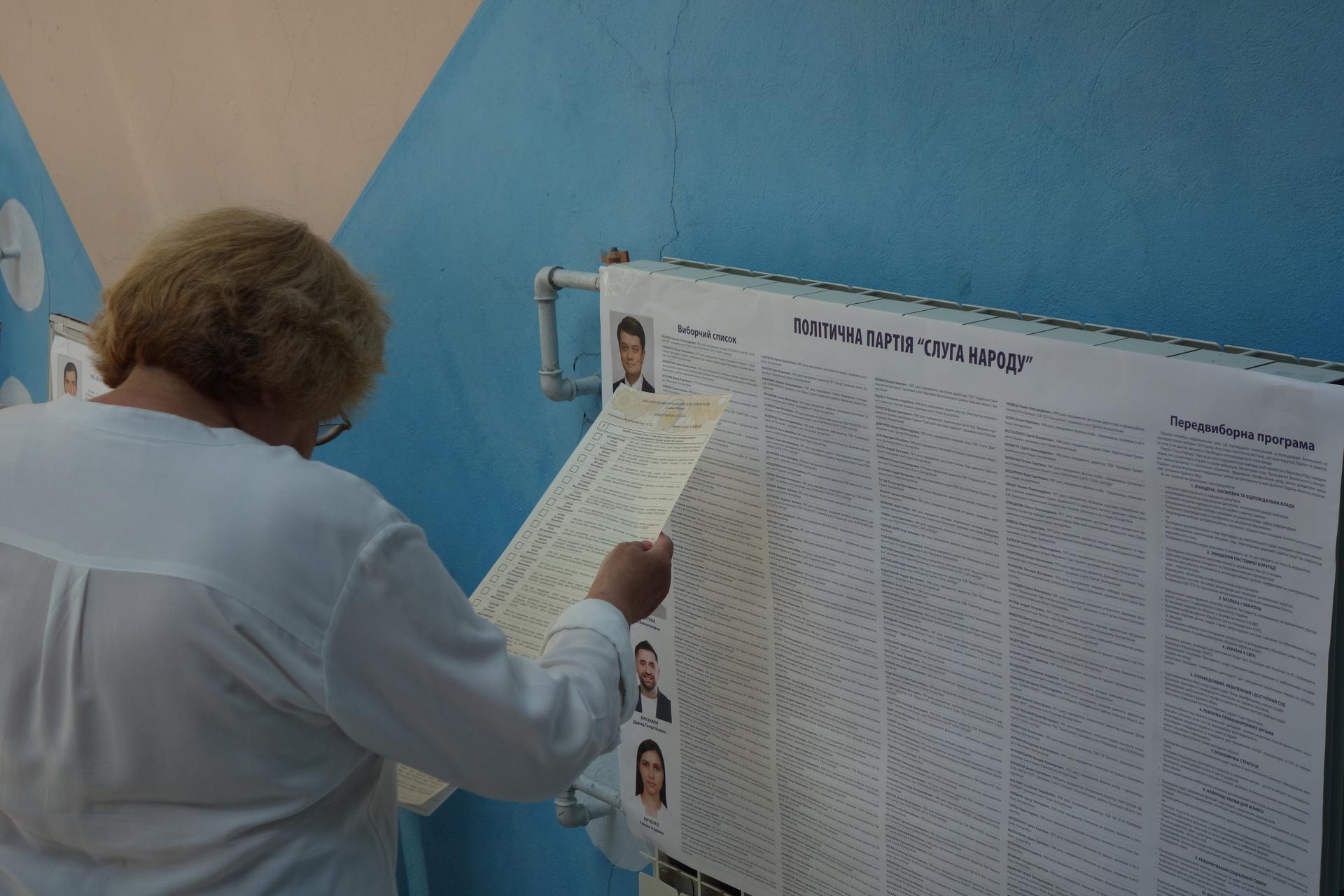

Shtepa stepped up as a candidate of the “Servant of the People,” the party of new President Volodymyr Zelensky, a former comedian. He and more than 200 other newcomers to Ukrainian politics took advantage of Zelensky’s unprecedented desire for change in the form of new lawmakers.

Related: This Ukrainian candidate is challenging language divisions in runoff

The explosion of the country’s political elite left a massive power vacuum that has triggered hope — but also uncertainty — over the ability of inexperienced lawmakers to deliver on Zelensky’s promises.

Two months ago, on inauguration day, Zelensky called for snap parliamentary elections, hoping to displace longtime Ukrainian politicians all over the country. The elections ended with a massive victory for Servant of the People candidates, who secured 254 of the parliament’s 450 seats — the first-ever single-party majority in the country’s post-Soviet history.

The pro-Russian Opposition Platform—For Life party took second place with 43 seats, while the parties of former prime minister Yuliya Tymoshenko and former president Petro Poroshenko secured 26 and 25 seats respectively.

“I feel like we’re back in 1993. … Zelensky has turned Ukrainian politics completely upside down.”

“I feel like we’re back in 1993,” said Balazs Jarabik, a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment think tank. “Zelensky has turned Ukrainian politics completely upside down.”

It’s not just a figure of speech. Most new faces will be coming from Servant of the People, which specified in the early stages of the campaign that only people who had never been deputy before would be accepted as candidates. Golos, a new party created by Ukrainian rockstar Svyatoslav Vakarchuk, enforced the same rule, though it only managed to capture 20 seats in the election.

The extent to which the Servant of the People won even stunned party insiders: Marina Bardina, a 26-year-old former activist and soon-to-be deputy, said the results in the single-mandate districts had “really surprised them.”

In Ukraine’s political system, half of the deputies are elected on nationwide party lists. The other half, however, run in local constituencies often controlled by local oligarchs — where Zelensky’s candidates were expected to struggle.

But “the power of [Zelensky’s] brand proved stronger,” Jarabik says, allowing candidates with little political experience and no name recognition to beat established figures simply by virtue of being “Zelensky’s candidate.”

Related: A mining town in Ukraine looks to one of their own for president

In the Odessa region, Oleksiy Leonov, owner of a pizza restaurant chain, managed to win against a politician who had held a seat in parliament since 1998 — and was running in his native district.

In another example, 25-year-old Oleksiy Movchan, project manager for an anti-corruption electronic tender company, prevailed in the eastern region of Poltava over Konstantin Zhevago, a steel magnate ranked as Ukraine’s seventh-richest man last year.

Now, however, some Ukrainians wonder whether the inexperience of these deputies could turn from asset to liability, as poll after poll emphasizes Ukrainians’ desire for radical — and speedy — change.

Anastasia Krasnosilska, a future deputy from Zelensky’s party and former board member of AntAC, one of the country’s most influential anti-corruption NGOs, told The World that the parliament would try to adopt a wide range of anti-corruption legislation in the first six months of their mandate.

This would include re-establishing anti-corruption state agencies previously discredited by scandals. They also plan to ease investigative procedures for NABU, the country’s main anti-corruption agency, as well as remove the legal immunity currently enjoyed by lawmakers — one of Zelensky’s most popular promises.

“They need training. … They need to be taught not just to push buttons.”

Given the stakes, can a group of restaurant owners, wedding photographers and actors successfully navigate the complex rules of parliamentary work? “They need training,” former president Petro Poroshenko scoffed in an interview. “They need to be taught not just to push buttons.”

Servant of the People has already tried to handle the criticism.

On July 29, it sent its 254 future deputies to a luxurious hotel near the Carpathian mountains for a one-week intensive course organized by the Kyiv School of Economics. The course, according to the school’s Facebook post, will include lessons in political strategy, macroeconomics and law, as well as communication.

Another question looms as to whether the biggest parliamentary faction in Ukraine’s history can sustain unity throughout its 5-year term.

Related: Comedian Volodymyr Zelenskiy set to win first round of Ukraine vote

While all deputies from Zelensky’s party are newcomers, their backgrounds differ wildly. Political analyst Anatolii Oktysiuk, co-founder of Democracy House, a think tank, has identified at least four groups: former activists, small business owners, former members of Zelensky’s production company and people close to Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky.

“I think my experience as an activist will benefit me … because I understand how to talk about and how to push these issues.”

Some of them have valuable experience: Bardina co-founded an NGO focused on gender equality issues and worked for the last five years as a parliamentary assistant to Serhiy Leshchenko, a respected reformist ex-deputy who failed to win a seat in the next parliament. “I think my experience as an activist will benefit me,” Bardina said on election day, “because I understand how to talk about and how to push these issues.”

Anastasia Krasnosilska’s advocacy work in the anti-corruption NGO AntAC also included lobbying for specific anti-corruption bills and monitoring parliamentary work on these bills.

But many others, like Sergey Shtepa or Oleksiy Leonov, do not have any parliamentary experience, which could complicate relations between deputies — Shtepa declined a request for an interview for this article.

“These groups also have different interests, which means there could be conflicts inside the party,” Oktysiuk said.

Despite these potential pitfalls, the situation is “a huge opportunity,” according to Oleksandr Lemenov, a lawyer and analyst at the Reanimation Package of Reforms, an NGO monitoring the reform process.

The majority enjoyed by Servant of the People in the parliament could allow Zelensky and his team to push through reforms without facing the hurdles faced by his predecessor. It’s also a unique opportunity to reduce the influence of oligarchs who have long held a tight grip on parliament.

“Whether they will succeed is anybody’s guess, nobody can say right now,” Balazs Jarabik said. “But we should give Zelensky the benefit of the doubt, because he has written a script and so far, everything has gone exactly as he wrote.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?