Indonesia’s newest Gen Z craze? Marrying someone you’ve never even dated.

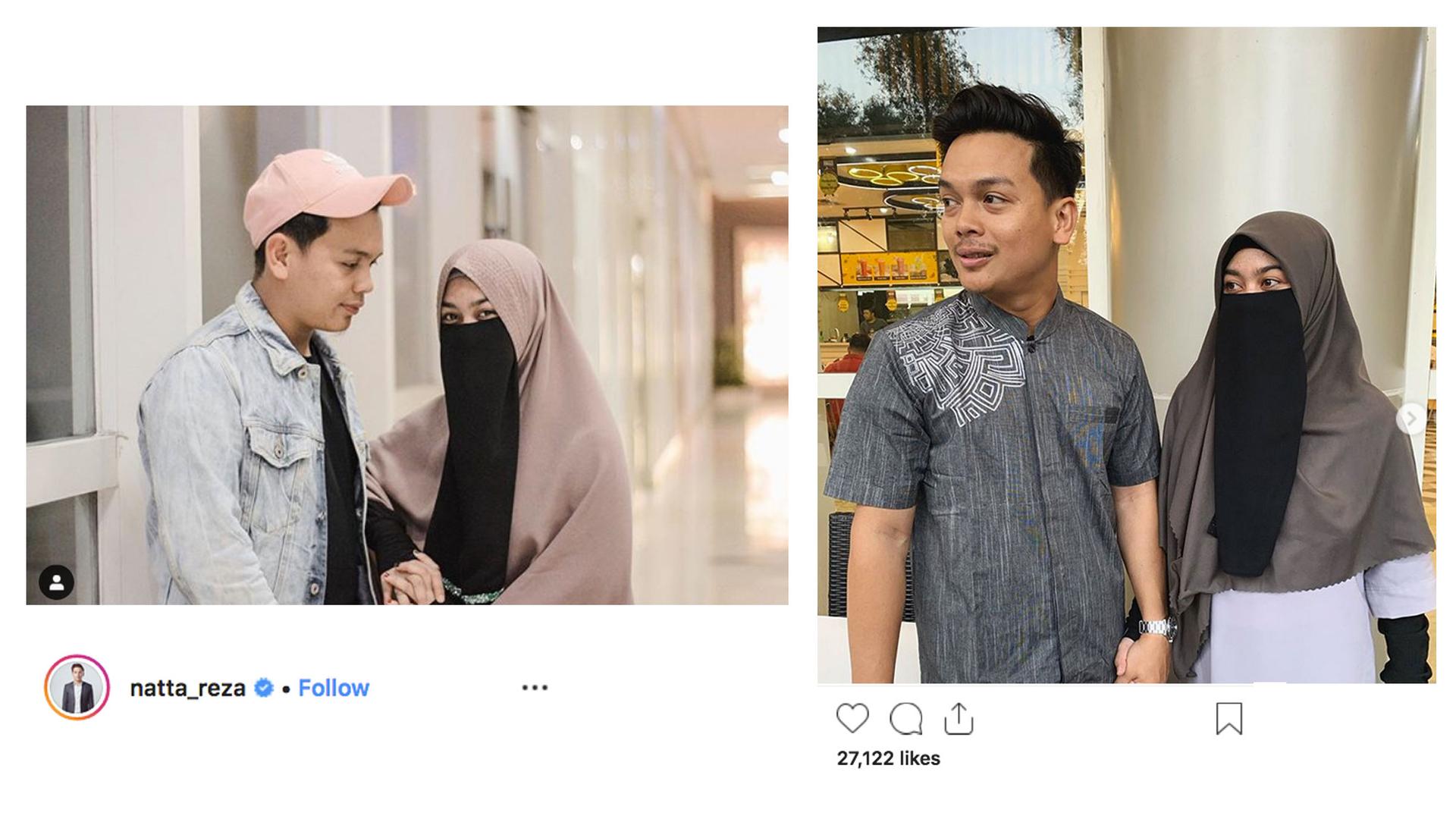

Indonesian social media influencers Natta Reza and his wife, Wardah Maulina, are shown. The couple regularly posts images depicting their marriage, untainted by dating, as a never-ending fairy tale, to their combined 2 million Instagram followers.

There’s nothing new about emerging generations embracing sexual mores that shock their elders. But many Indonesians, especially those with a more liberal disposition, really didn’t see this one coming.

There’s a fast-growing, Gen Z subculture in the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation. It’s personified by the group Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran, which means “Indonesia Without Dating.”

It’s exactly how it sounds: a movement to eliminate premarital dating, derided as a sinful, Western ritual that will ruin your life. These young Muslims instead want to push their island nation, long branded as religiously moderate, toward practices that more closely resemble norms in, say, Saudi Arabia.

“I really would never have thought, 20 years ago, when we were just going through the democratization process … that we’d become this kind of society,” said Devi Asmarani, founder of a feminist online magazine called Magdalene.

That sums up a sentiment shared by many Indonesians who remember the late 1990s, when a US-supported regime, headed by the dictator Suharto, began to unravel — and youth of that era imagined a freer, more open society blooming in its wake.

They are now stunned to see Gen Z kids popularizing attitudes so puritanical that, by comparison, America’s 1950s-era dating culture seems risqué.

“It’s pretty much about domesticating women. Cook. Be good to your husband. Serve your husband well in bed. And then you will have a good life. It’s ridiculous.”

“It’s pretty much about domesticating women,” said Dina Afrianty, an Indonesian scholar who studies women’s issues at La Trobe University in Australia. “Cook. Be good to your husband. Serve your husband well in bed. And then you will have a good life. It’s ridiculous.”

These young, orthodox Indonesians are hardly anti-modernists. “Indonesia Without Dating” is largely an online movement — propelled by “likes,” memes, Instagram videos and WhatsApp chat groups.

The core message is fairly simple. Casual hangouts with other boys and girls is forbidden. Face-to-face, premarital contact with the opposite sex must be supervised by a family member. The goal is getting married young, which is depicted as a shortcut to happiness.

Related: Indonesia’s Muslim youth find new heroes in Instagram preachers

The movement swirls around a profit-seeking business, Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran, which sells a variety of branded accessories: T-shirts, hijabs, keychains and trucker hats.

But the business also charges young people roughly $13 to enroll in WhatsApp chat rooms, which serve as advice sessions for those eager to find a partner.

Far from freewheeling, the chat groups are moderated in a way that is “super strict, rigorous and almost militaristic,” according to Elma Adisya, a Magdalene reporter who enrolled in Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran for an investigation.

The conversations are kept ultrapious, she says, and members are nudged to attend local “seminars,” often held at mosques, where young women publicly take vows against dating.

Teenage girls who are still dating boys may also be encouraged to dump them over the phone — sometimes in front of hundreds of other cheering girls (and thousands of viewers on YouTube). The group is fond of preachy lectures, such as this one posted to its Facebook page: “Oh, my sister, remember these words … dating will not bring you true love, for it is only a Satanic trap.”

The messaging can be ponderous. But the real star attraction at these events, Adisya says, are social media influencers, namely married male heartthrobs who speak to rooms full of young, excited hijabis.

“It’s like attending a boy band concert. The girls start squealing, saying, ‘Oh, my God! He’s so cool!’ It’s like fan-girling.”

Their emergence onstage can bring on gleeful screams worthy of a Justin Bieber performance. “It’s like attending a boy band concert,” Adisya said. “The girls start squealing, saying, ‘Oh, my God! He’s so cool!’ It’s like fangirling.”

The reigning king of this scene is Natta Reza, an Indonesian guy in his late 20s who is blessed with a perfect swoosh of black hair. His career is built upon a dreamy origin story. Several years ago, he spotted a young, veiled woman on Instagram, liked one of her photos and ended up chatting with her online.

He was instantly smitten. Within hours of that initial like, he proposed — and now his wife, Wardah Maulina, is a star in her own right. To their combined 2 million Instagram followers, they depict their young marriage, untainted by dating, as a never-ending fairy tale.

Reza has even used this narrative as a launch pad for his music career. His latest single, which in translation means “Dream Lover,” is nearing 7 million views on YouTube.

Both of them intersperse their anti-dating testimonials with endorsements: beauty products, junk food and halal juices promising quick weight loss. This is mixed in with the occasional religious lecture, including endorsements of polygamy, which is traditionally considered somewhat taboo in Indonesia.

The takeaway for college-aged Indonesian women, Afrianty said, is “Why make your life so difficult? Why work so hard to get a job? You can become someone’s second, third or fourth wife? Easy!”

This puritanical craze is hardly all-consuming. The mores it promotes are not the norm in Indonesia. But its power to sway young minds is undeniable, Afrianty says. It also belongs to a larger trend often called the “Arabization” of Indonesia.

Seafaring traders first brought Islam to Indonesia more than a millennia ago but, since then, societies scattered across the archipelago have cultivated their own Islamic rituals and ways of interpreting the faith. But in more recent years, Saudi Arabia has promoted its own brand of puritanism in Indonesia (along with many other Muslim-majority nations) — and has found a somewhat receptive audience.

This orthodox wave has taken on a life of its own. A subset of young Indonesians appears to be deciding that a hyper-conservative lifestyle is ideal. This has led to a flourishing of memes — and profits.

Tapping lovelorn angst is lucrative. Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran is believed to have at least 600,000 members — and each paid an enrollment fee of 180,000 rupiah or roughly $13, more than the daily minimum wage in the capital of Jakarta.

“This is all part of a growing Shariah economy in Indonesia,” Asmarani said. “It’s not just about fasting or praying five times a day. It’s all about fashion … and labeling everything ‘halal’ to increase sales.”