Ayatollah Khamenei says nuclear weapons are ‘forbidden under Islamic law’

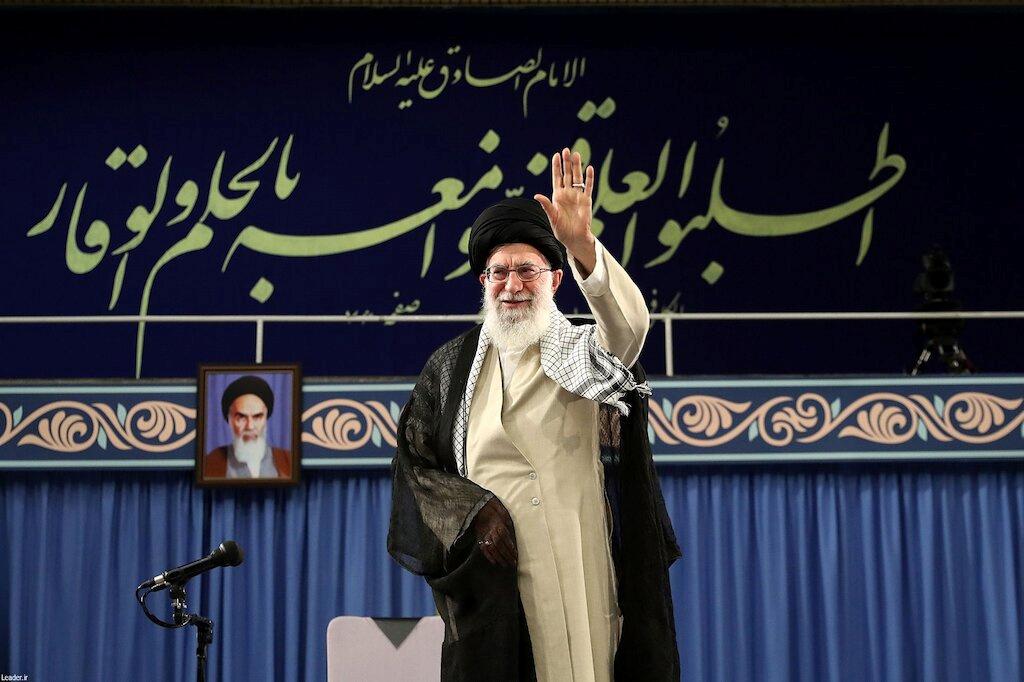

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Tensions have been high between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran. Over a year after the United States decided to pull out of the Iran Nuclear Deal, President Donald Trump has suggested he is open to dialogue with Iran about making a new deal. So far, Iran has not been enthusiastic about this proposal. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei recently signaled that he would not want to negotiate with the US under current circumstances. He also said that Iran was not looking to acquire nuclear weapons for a surprising reason — that they were illegal under Islamic law.

To help understand what Ayatollah Khamenei meant and what implications this statement could have, The World’s host Marco Werman spoke with Omid Safi, a professor of Iranian studies at Duke University and the director of the Duke Islamic Studies Center.

Marco Werman: Omid, Iran is officially an Islamic republic. Does Islam forbid the use of nuclear weapons?

Omid Safi: I think it’s good to start by realizing that when the Koran was revealed in the 7th century, there were no nuclear weapons in the world. The Koran, Bible and Torah don’t say anything about nuclear weaponry, chemical weaponry or biological weaponry. What the Koran has, and what the Islamic tradition has had over the last 1,400 years is a clear emphasis on what it calls the sanctity and the dignity of human life. What Ayatollah Khamenei, the supreme ruler of Iran, is referring to is that in 2010, almost 10 years ago, he issued a juridical opinion stating that weapons of mass destruction — nuclear, chemical and biological — are against the rulings of Islamic law.

Related: Iran rolls back nuclear pledges but stops short of violating pact

This statement from the ayatollah did make me scratch my head because if nuclear weapons are forbidden under Islamic law, did it make you wonder what the Iran nuclear deal was really all about?

Well, the Iran nuclear deal was very specifically to make sure that Iran’s nuclear energy capabilities remained at the level of nuclear energy and was never allowed to be enriched to the point of developing nuclear weaponry.

Right, but if the ayatollah says that they actually don’t want them anyway because it’s forbidden, then it seems like the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was a lot of work for nothing. Was it necessary?

It was necessary in order to lift crushing and crippling sanctions imposed largely by the United States, in alliance with global powers and allies, upon Iran. The sanctions have had a crippling impact on everything from medicine, to industry, to airplane parts and has really isolated Iran economically, which has led to a level of inflation in Iran that every Iranian complains about.

Professor Safi, why do you think the ayatollah made this statement now?

The ayatollah has been making this statement for the last 10 years or so. I think they find themselves at a time where they’re dealing with an unstable American president. It is very difficult to think about what the actual policy of the United States in the region consists of. We’re also seeing the rise of dictatorial and authoritarian regimes all around the world, whether you’re talking about Vladimir Putin and Narendra Modi and Abdul Fattah al-Sisi and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. We’re dealing with a rise of anti-democratic movements all around the world. Bashar al-Assad in Syria and too many others to name. I think the rulers of Iran have a fascinating way of speaking in a very adversarial way, but actually negotiate in a very pragmatic and diplomatic way. I think they are trying to get America, and whatever global power is still left, back to the negotiating table so that another deal can be worked out.

As to the ayatollah’s statement, if it’s all about human life and dignity, this ban on nuclear weapons, how well does Iran do on other aspects of human life and dignity?

Well, it’s a mixed record, as are the majority of the countries in the region. On one hand, it is certainly true that the Iranian regime has a rather atrocious policy of human rights towards its own dissidents. They certainly are in support of many movements around the region that could never be mistaken for being pacifist movements. But on the other hand, their main adversary, the United States, is in bed with Saudi Arabia, which is the main ideological exporter of extremism around the world through the Wahhabi strand. I think what we have to deal with in the case of Iran is that it’s a developing democracy where the majority of the population being under 30 years old are voting for a moderate candidate, and they’re dealing with an 80-plus-year-old supreme leader who will have to be replaced at some point. I think the question for Iran, being an ancient and proud civilization and being a democracy in progress, when their hard-line ruler says, “We have no interest in nuclear weaponry and please bring the United Nations and bring the global powers and verify that we’re not developing nuclear weaponry” — I think this represents an extraordinary opportunity for anybody in the world that would like to see a path other than warfare and destruction.

Related: Iran may sail around US sanctions with ‘cloaked’ tankers

Earlier this week, the foreign minister of Iran responded to a question about nuclear weapons, and he said Ayatollah Khamenei long ago said, “We’re not seeking nuclear weapons” by issuing a fatwa banning them. Professor Safi, we hear the word fatwa a lot. Explain how that applies in matters of national defense? Can a fatwa be revoked?

The fatwa is simply the opinion of a jurist. Not [just] anybody can issue a fatwa. It is not as if you or I could just open up our own website and start issuing fatwas. An analogy would be that not anybody can issue a Supreme Court decision. You have to become an attorney and a judge to be appointed to the Supreme Court and a case has to be brought in front of you and then you rule on the basis of that.

But could you imagine a situation where the 80-some-year-old ayatollah is replaced by somebody who may be more in line with the political leanings toward building nuclear weapons?

I think the reason that I have a hard time seeing that being the case is because of the underlying principle, which is this sanctity of human life. That part is enshrined in Islamic law. It’s true that the Islamic tradition, no more than the Christian tradition or the Jewish tradition, has never been a pacifist tradition as a whole. They’ve all had a notion of, if you would, a just war. This specifies the terms and conditions that have to be met in order for you to go to war, how you conduct yourself in war and most importantly, how do you get yourself out of war. It’s possible that some of those terms and conditions could be defined and redefined with the passage of time. As somebody who studies this tradition every day, what I have a hard time seeing happen is that a newly qualified jurist would all of a sudden say that the indiscriminate killing of civilians, which is what weapons of mass destruction are designed to do, of the type that the United States put on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is permissible under the letter if not the spirit of Islamic law. I think that really flies in the face of everything that we know about a 1,400-year juridical tradition.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.