‘I get screamed at in the streets’: Colombia’s patience with Venezuelan migrants wears thin

“I would say 99% of people here have treated me well,” says Eric Sanchez, the violinist from Venezuela, who plays music in Bogotá’s fashion district, Colombia, May 9, 2019. But other Venezuelan migrants say they’ve been the target of slurs and insults since their arrival in Bogotá.

In Bogotá’s fashion district, Venezuelan migrants stand below traffic lights, holding cardboard signs that plead for help. Others offer small candies to well-heeled couples walking by, hoping to garner some pocket change.

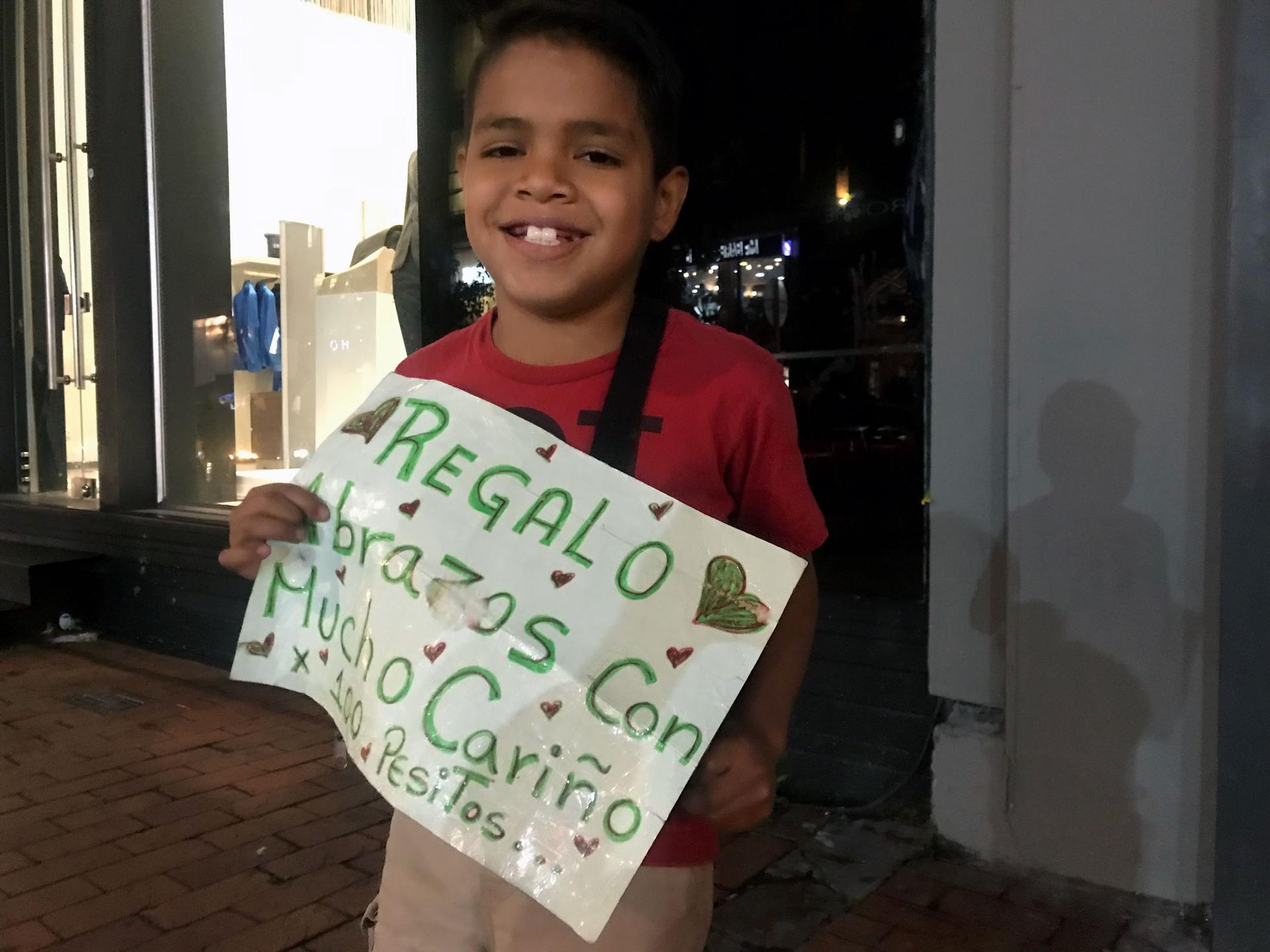

Outside the Andino Center, one of Bogotá’s most luxurious shopping malls, a 9-year-old Venezuelan boy announces repeatedly that he is offering hugs in exchange for coins. “Only 100 pesos,” reads his sign.

These scenes are a harrowing reminder of the crisis unfolding in Venezuela that has forced millions to flee to nearby Colombia, Ecuador, Brazil and Peru.

According to the United Nations, more than 3.7 million Venezuelans have left over the past four years to escape food shortages, high crime rates, and hyperinflation that has rendered the local currency so worthless that some artisans have used it to make origami-style handbags.

Colombia has taken in 1.2 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees since 2015. Last year, Colombia handed out temporary residence permits to 400,000 Venezuelan migrants and refugees, according to Colombia’s top migration official, Felipe Muñoz.

Related: As Venezuela’s crisis worsens, thousands flee to Colombia

The government has welcomed newcomers by offering health services and providing pathways to legal work.

But while the government undertakes flexible immigration policies, Colombian citizens’ patience with newcomers is starting to wear thin. In some cases, the mass arrival of Venezuelans has led to xenophobic outbursts.

“I get screamed at in the streets. … Some people have helped me, but others tell me to go home and find a job.”

“I get screamed at in the streets,” says Kelvin Rojas, a 23-year-old migrant who arrived in Bogotá two weeks ago.

Rojas begs for money with his 1-year-old son. In exchange for donations, he hands out worthless Venezuelan bolivar bills that he brought from home.

“Some people have helped me,” he says. “But others tell me to go home and find a job,” he adds, before recalling some of the slurs and insults people have launched at him.

Other migrants have fared worse.

In October 2018, a Venezuelan man was beaten to death by a mob in a Bogotá slum after false rumors spread through social media that Venezuelans living there were kidnapping children. The rumors were likely started by people trying to get the migrants out of the neighborhood.

In Ecuador, dozens of Venezuelans’ homes got ransacked in a small border town in January 2019, after a Venezuelan man held his Ecuadorian girlfriend hostage, and killed her in front of police.

In August last year in the northern Brazilian town of Paracaima, rioters burned down an informal tent village set up by Venezuelan refugees, after one of them was accused of assaulting a local merchant.

To simmer tensions and facilitate integration, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees launched anti-xenophobia campaigns throughout South America and works with local newspapers to produce positive stories about migrants and refugees.

Related: Defiant Maduro blocks humanitarian aid at Colombian border

The World Bank also stressed that migrants have a positive impact on Colombia’s economy as well as other countries in the region — despite the costs related to hosting them — noting that once they have legal residence, they can open tax-paying businesses or hold regular jobs.

But in some industries, workers have complained that the arrival of Venezuelan immigrants is driving wages down.

“A Colombian will not work for you for less than the minimum wage. … But what I have seen is that in some parts of town, Venezuelan barbers were working for half as much.”

“A Colombian will not work for you for less than the minimum wage,” says Arnold Bonilla, a barber in Bogotá’s financial district. “But what I have seen is that in some parts of town, Venezuelan barbers were working for half as much.”

Bonilla ads that Venezuelans are not the only ones to blame for “unfair” competition, but also abusive employers who hire workers illegally.

Silvia Ruiz, a Colombian human rights lawyer, says that some of the recent tensions with Venezuelan immigrants are not necessarily derived from xenophobic sentiment, but from a phobia toward the poor that has surfaced elsewhere in the world: Academics call it aporophobia.

“Colombians treat tourists extremely well, and we go out of our way to show them our hospitality,” Ruiz writes in a column in the Colombian daily El Tiempo. “At the same time, some of us are in favor of removing Venezuelans from tent camps (in cities) without asking ourselves where they will sleep next.”

Related: Malnourished Venezuelans hope urgently needed aid arrives soon

“What may be bothering us is not really foreigners,” she says. “But the poor foreigner without resources, who asks for things, does not offer something and makes us feel uncomfortable.”

“What may be bothering us is not really foreigners, but the poor foreigner without resources, who asks for things, does not offer something and makes us feel uncomfortable.”

And that might also explain why migrants with more complex skills seem to be less concerned with discrimination than those who try to compete with locals for construction jobs, or those who beg on the streets.

Outside the ritzy shopping mall where some impoverished migrants chase pedestrians for pocket change, a group of five Venezuelan musicians plays pop songs for tips, using a viola, cello, guitar and percussion box. All of them were classical musicians in Venezuela. Now, they make a living playing in the streets as well as at private events.

“I would say 99% of people here have treated me well,” says Eric Sanchez, the violinist. He adds that a woman once stopped her kid from approaching the group, mentioning their Venezuelan origin, but that it was an exceptional moment. “There’s no way that is going to stop us from pursuing our goals,” he says.

Kelvin Rojas, who begs on the streets with his son, has a less optimistic view of life in Colombia.

“It’s not easy for us to be here, asking for help,” he says. “I don’t wish anyone this fate.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?