As Trump eyes more family detention, experts say it puts kids at risk

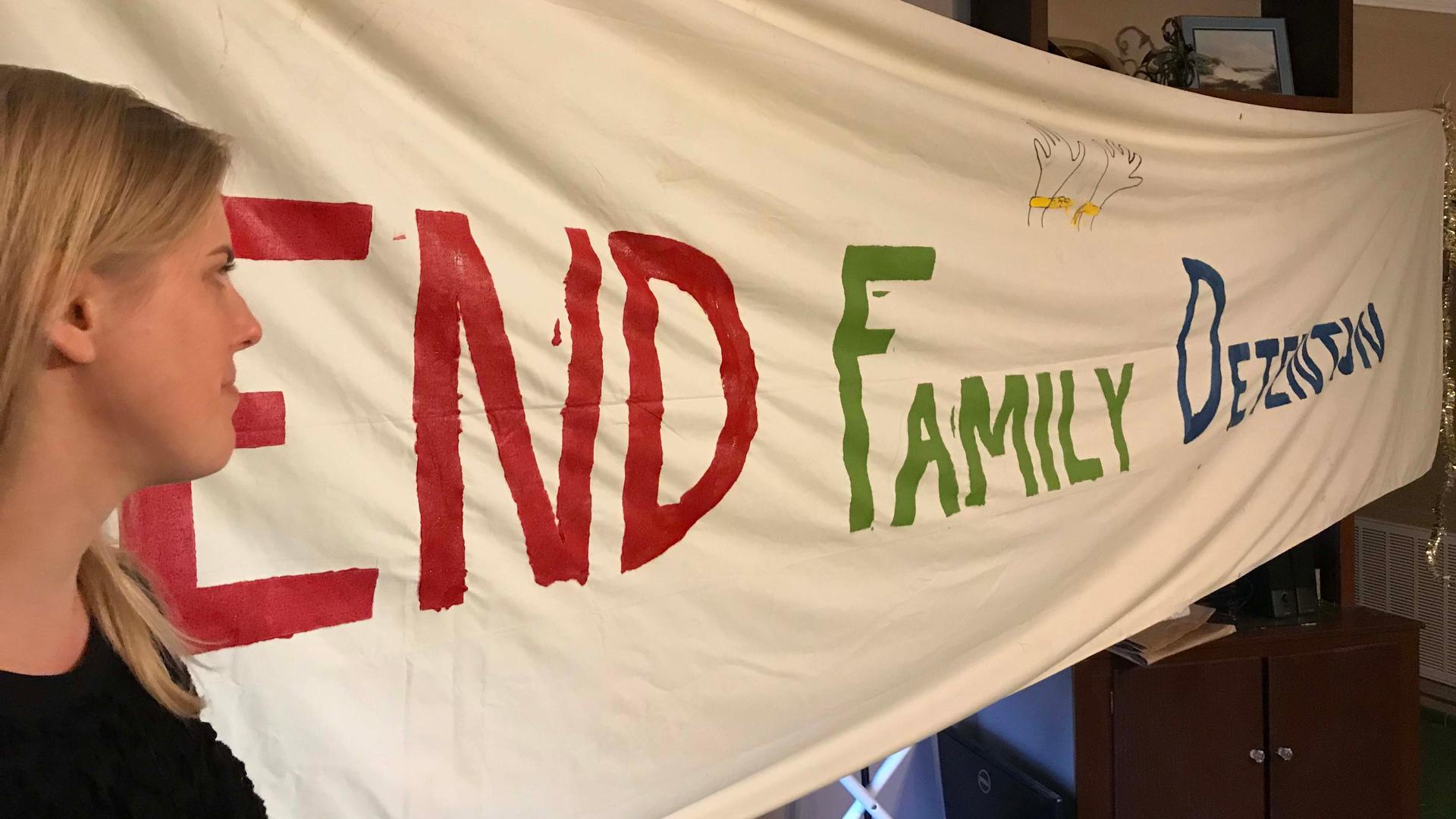

Katy Murdza is an advocacy coordinator with the Dilley Pro Bono Project, which helps families prepare for asylum procedings.

This story was reported in collaboration with KQED Public Radio.

As the number of families seeking asylum at the US-Mexico border grows, the Trump administration is contemplating detaining more parents with their children while they await a chance to go before an immigration judge. The government recently announced it will spend $40 million to build two tent cities for migrant families in Texas.

Most of the families currently arriving from Central America are being released into the US and given a notice to appear at an immigration court. Others are waiting in Mexico. A small minority, just 600 mothers and children, are detained together, according to an official with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, mostly at the South Texas Family Detention Center.

The facility next to the rural city of Dilley can hold up to 2,400 mothers and their children and is the largest family detention center in the country, but it has come under scrutiny as inspectors and detained families report instances of inadequate care. ICE has twice refused KQED’s request for a tour of the facility.

From the nearby road, large tents and tall light poles are visible. Katy Murdza, an advocacy coordinator who helps families detained at Dilley, says at night the detention center’s floodlights are so bright, there’s a glow a mile away. She says some of the mothers have told her the lights, which are never turned off, make it hard to sleep.

Murdza is with the Dilley Pro Bono Project, which helps families prepare for the first hurdle in the asylum process: convincing US authorities they will be persecuted or tortured if they return to their home countries.

Every time legal advocates enter the detention center, they undergo a rigorous security check, Murdza says. Similar to an airport inspection, they have to take off belts and pull all of their belongings out of their bags to show to staff.

“There’s a lot of things you can’t bring in,” she said. “You can’t bring in makeup, hand sanitizer, anything that ICE considers contraband.”

To speed things up, Murdza and many of her colleagues use plastic, see-through backpacks.

Once inside, attorneys and legal advocates can only access meeting rooms inside a trailer, or a courtroom where mothers and children present their cases to a judge via video conferencing.

Murdza says one of the challenges when helping families is managing the needs of kids. Because they’re often too sick to go to daycare, or too traumatized to be separated from their moms, children tag along to legal consultations.

“We’ve had kids throwing up in the meeting with the mom,” Murdza says. “Moms are deciding between going and waiting for hours at the clinic or meeting with their lawyer.”

Part of Murdza’s day is spent filing email complaints to ICE on behalf of clients she says aren’t receiving the care they need, like mothers with pregnancy complications or children losing weight quickly.

In a April 23 email, ICE said allegations were being made by “non-clinicians with very limited access and knowledge to the full range of services and care provided.”

ICE added that migrants at Dilley who require a higher level of care “are referred to the local hospital network.”

But not everyone agrees the care is adequate at Dilley, especially for children.

Dr. Scott Allen, who was contracted by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties to investigate the quality of medical care in family detention, found many problems.

Starting in 2014, Allen and his colleague, Dr. Pamela McPherson, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, visited all of the family detention facilities in the country to interview staff, detainees and review medical records.

In addition to Dilley, they toured the Karnes County Residential Center in Karnes, Texas, the Berks Family Residential Center in Berks, Pennsylvania, and the now-defunct detention facility in Artesia, New Mexico.

The doctors found problems with recruiting and retaining qualified pediatricians and mental health care providers, and a lack of access to emergency and specialty care, given the remote locations of most of the detention centers.

“The government had great difficulty in keeping children safe and meeting their own standards.”

“The government had great difficulty in keeping children safe and meeting their own standards,” Allen said in a phone interview earlier this year. “That has been continuous across facilities and continued until our last investigation.”

But the issues are not necessarily the fault of dedicated medical and custody staff, he cautioned.

“We found a lot of good people in these facilities, both from the contracting agencies and the government agencies, Homeland Security, who are working really hard trying to keep these children safe,” Allen said. “The problem is they are not being given adequate resources.”

Last June, after President Donald Trump threatened to expand family detention, Allen and McPherson sent a letter to Congress cautioning against the move.

“Our concern is that if you rapidly expand, the logistical challenges are multiplied and the number of children placed at risk is also increased,” Allen said.

The Trump administration initially proposed to increase the number of beds for family detention from 3,400 to 15,000.

The doctors, now represented by lawyers at the Government Accountability Project, are blowing the whistle again.

Both Allen and McPherson still work for Homeland Security as subject matter experts, but neither has been asked to investigate family detention since 2017.

Last month, the doctors sent another letter to Congress asking members to investigate whether Homeland Security has conducted any additional investigations of medical care and conditions in family detention.

The Trump Administration also faces legal obstacles to expanding family detention, including the 1997 Flores settlement, a long-standing agreement that set standards for humane treatment of migrant children in government custody.

“The settlement says you can detain children,” said Bill Hing, a professor at the University of San Francisco School of Law, “but if you detain children, you’ve got to meet certain requirements.”

Hing has served as a monitor for the Flores lawsuit, visiting government facilities holding kids, including the South Texas Family Residential Center. He says judge overseeing the settlement has made it clear that the facility in Dilley can only be used to hold children with their parents temporarily.

The Trump administration has challenged that interpretation in the Central District Court in California, arguing that the protections for migrant minors should only apply to children who arrive to the US without a parent.

Hing disagrees. “Even if you’ve got your mom with you, you’re still a child,” he said.

Hing visited the family detention center in Dilley about a year ago. He says it looked like a campus, with clean classrooms, a library and places to exercise. But then he saw a group of mothers in an orientation meeting, with young, but lethargic children on their laps, many of them sick.

“That’s when you do say to yourself, ‘Really, in the United States we have this where we’re detaining mothers and children?’”

“They just didn’t have any energy,” Hing recalled. “It was so sad to just watch this. That’s when you do say to yourself, ‘Really, in the United States we have this, where we’re detaining mothers and children?’”

But with thousands of families coming to the border every week, ICE may send more families to detention.

Back in Dilley, Murdza says no families have to be locked up.

“ICE can choose whether or not to detain someone,” she said. “And that’s why we are advocating for the end to family detention. It’s not something that’s required.”

We’d love to hear your thoughts on The World. Please take our 5-min. survey.