In search of refuge during the American Revolution, this enslaved black man joined the British army

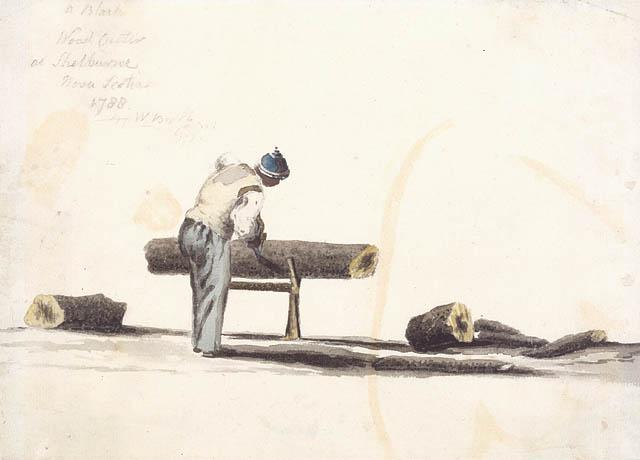

“A black wood cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia.” This watercolor sketch by Captain William Booth, Corps of Engineers, is the earliest known image of an African Nova Scotian.

The American War for Independence was a complex birth of a nation, steeped in both noble ideals and confusing contradictions. The founding document boldly declared that all men were created equal, but in reality, some of those same men owned fellow men, just of a different color.

For people of color, what was their best option? What good would the freedom of a nation be to them if it did not involve their personal freedom?

Questions of loyalty and allegiance were not limited to any one race or ethnicity. Thousands of colonists from every background for one reason or another chose to retain their loyalty to that of the only government they had ever known — the British. Whatever grievances colonists had, and all had some, they figured an armed rebellion against their kin was not the solution. Loyalties could shift as well (see: Benedict Arnold), adding to the complexities of the conflict.

Thousands of such men, known commonly as Loyalists, were embodied by the British into military regiments, some led by Americans, some by professional British officers. Among the latter was one regiment commanded by Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe, a 20-something who had served in the British Army since 1770. The regiment he commanded was known as the Queen’s Rangers. Raised in 1776, the Queen’s Rangers eventually reached a strength of 11 companies of infantry and five troops of cavalry.

After five years of fighting, American independence was still not decided or guaranteed. May 1780 saw a large British force besieging Charleston, South Carolina, the largest city in the south. Its capture on May 12, 1780 netted the British over 5,000 prisoners and dealt then-General George Washington and his cause a serious blow.

Included in the victorious troops were Simcoe and his Rangers. Enjoying the countryside and the relative calm after their victory, Simcoe took the liberty of informing his friend, the famous British Adjutant General John André that he had taken possession of four young enslaved black men, whose owner was none too happy for their absence.

“I understand Mrs. Elliot is to apply to the Commander in Chief for four Negro boys now with the Queens Rangers, & I think it necessary to explain to this matter” Simcoe wrote. He added, “The Boys are Taylors & Musicians, & are at this time clothed in the Rebel Artillery Uniform, which her Husband commanded.”

This was no doubt a reference to the late Lt. Col. Barnard Elliott, commander of the 4th South Carolina Regiment, an artillery unit.

Regardless of the circumstances, the four young men, now formerly enslaved, embraced the opportunity afforded them by the British. British policy on the matter walked a tightrope. While officially offering freedom to enslaved black people who joined the British, it only applied to those who had belonged to those in rebellion; those belonging to Loyalists had no such opportunity.

Another caveat in embracing formerly enslaved black people was a prohibition on their serving in most capacities in the army, primarily serving under arms in the ranks. There were other opportunities, however.

Thousands of formerly enslaved black people aided the British by serving in non-combat capacities through organizations known as the “Civil Branches” — organizations responsible for feeding, housing and fueling the army. Others served in the Royal Navy, onboard privateers or as unarmed pioneers (military laborers) either attached to regiments or in distinct corps.

One more option was that of musician. Military musicians, i.e. drummers, fifers, trumpeters and hornsmen all played an important role in communicating orders, whether in battle, on the march or in camp. There was no prohibition on blacks serving in this capacity, and officers like Simcoe utilized this loophole to his corps’ advantage.

Of the four young men he took possession of at Charleston, one is believed to have gone by the name of Barney. Barney was born in America around 1763, making him 16 years old at the time of his joining Simcoe. He would be taught to play the trumpet and serve as the trumpeter to Captain David Shank’s Troop of Cavalry in the Queen’s Rangers.

Far from a lowly position, trumpeters, like the other musicians, were paid two pence more a day in pay than common soldiers, a sign of the importance they held in the regiment. With his trumpet, a fine green uniform, a sword at his side and most likely a pair of pistols in their holsters, Barney followed his regiment through Virginia during the tumultuous spring and summer of 1781.

While the Americans under George Washington faced off against the British under Sir Henry Clinton at New York, their lieutenants, the Marquis de Lafayette and Lord Cornwallis respectively, played a game of cat and mouse in Virginia. Moving on to Williamsburg on June 26, 1781, Cornwallis left Simcoe behind with his regiment and a few others to gather cattle and provisions for the army.

At a Virginia location called Spencer’s Ordinary, Lafayette sent forward a detachment of his army to cut off and destroy Simcoe and his men. Among the first to spot the danger was the trumpeter Barney.

Stationed as a “vidette” (a cavalry sentry), Barney recognized that the enemy cavalry would surprise his troop without some fast thinking on his part. Putting spurs to his horse, he galloped off in the opposite direction, shouting orders to men as if they were in front of him. The men of his troop, seeing the deception — and danger — quickly mounted their horses and joined the battle.

In the words of his commander, Simcoe, written later to the Secretary at War: “[Barney] in the consequent Charge of Cavalry was distinguished by Fighting hand to hand with a French Officer who commanded a Squadron of the Enemy & taking him Prisoner. When the Cavalry afterwards charged the Rebel Infantry, He by his gallantry preserved the Life of his Captain & was severely wounded.”

Wounded but victorious, Barney continued with Simcoe and the Queen’s Rangers during the Siege of Yorktown that October, the battle that saw Cornwallis surrender his army and all but guarantee America’s freedom.

But what of Barney?

“His Activity had made him so remarkable That I personally interfered with The Baron Steuben at the Surrender of York Town to obtain that He might not risk the Hazard of being sent Prisoner into the Country,” Simcoe wrote.

Securing safe passage back to New York City on parole, Simcoe took Barney along with him, not only there, but quickly thereafter to England, where he remained for years. Having been given his freedom and served his king most honorably, Simcoe recommended Barney, now officially going by the name “Barnard E. Griffiths” to a means of support for his service: the Chelsea pension. The pension was meant as a financial support in old age and illness, and in the words of his former commander, “He has no other means of reaping the Protection his Services in The Opinion of Every Officer of the Corps as well as mine most amply merit.”

Barney received his pension and his freedom. His story is only unique in that it has come down to us through records of the time, many of which are long since gone.

Thousands of formerly enslaved people eventually settled in Nova Scotia and elsewhere under the British flag. They may not have been on the side of a nation fighting for its freedom, as some did, but their service earned them their own personal freedom, passed down to their posterity today.

Todd Braisted is a historian, author and researcher of Loyalist military studies.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!