Illustrator’s sketches from a border bus station show a ‘miserable, degrading and demeaning’ experience

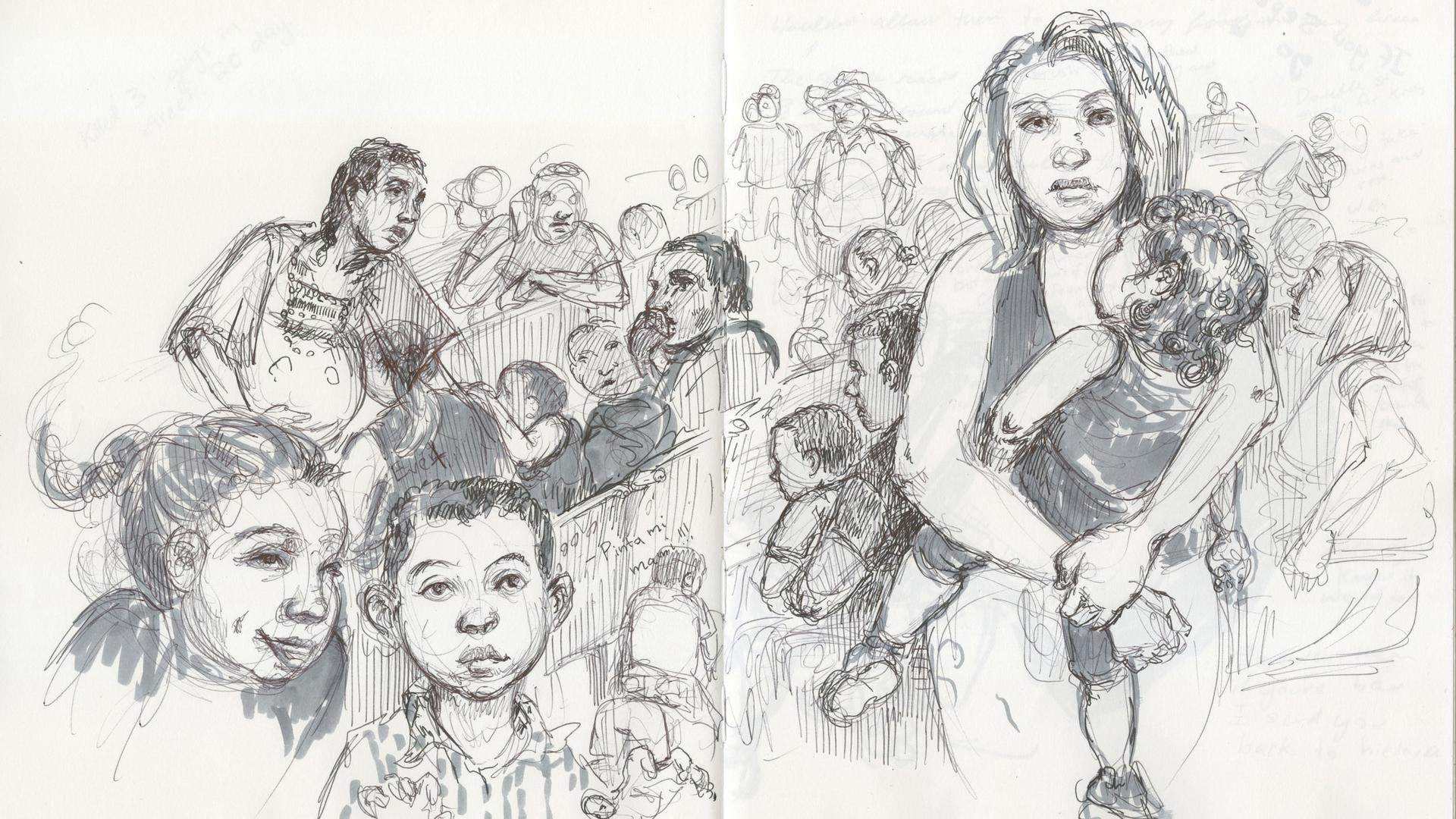

Molly Crabapple spent time in a McAllen, Texas, bus terminal sketching the scenes she witnessed. Here is one of here pen and ink illustrations showing a chaotic scene of women holding children in a crowded area.

When asylum-seekers are released to await a hearing, the first place some go is to a bus station. Bus stations have become pivot points for migrants.

Artist and writer Molly Crabapple, whose projects include “Brothers of the Gun,” an illustrated collaboration with Syrian war journalist Marwan Hisham, and her memoir, “Drawing Blood,” spent time in a McAllen, Texas, bus station to take in the scene.

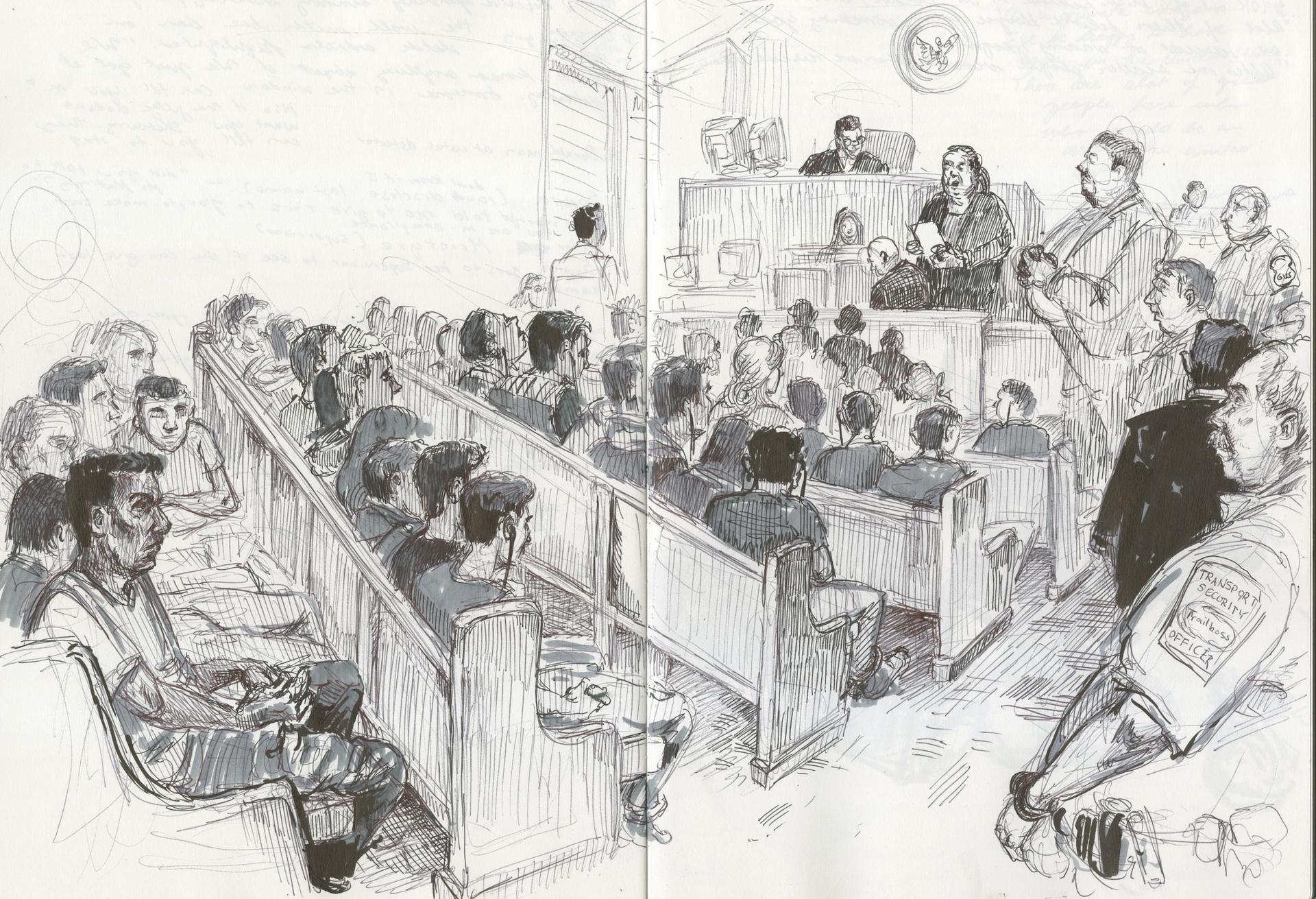

Crabapple sketched several images for her “Scenes from the Border Crisis” piece in Rolling Stone from the McAllen terminal and talked to The World about the experience and shared some of the images she sketched.

Related: After two boys’ murders, migrants and advocates fear new ‘remain in Mexico’ policy

The World: So you don’t take photos and then draw based on those images later, right? You’re taking in the scene and sketching at the same time?

Molly Crabapple: It depends on the assignment but for this particular thing that we’re talking about, those were all things that were drawn live.

So I imagine this has got to be kind of hard to do because so much happens in the course of a few minutes — like back in July you captured the moment a mother was reunited with her son. They had been separated at the border and you drew this little boy with a teddy bear in his mother’s arms and as he said, when they hugged again at the airport arrivals, it was like they were fused together. What is it like observing something so emotional and drawing it in the instance?

Well, I was crying. I had spent the previous day with that mother, Doña. She was talking about what it felt like to have her son taken from her, to be stuck in detention and then finally seeing her reunited with this little boy. So, I’m crying while I’m trying to draw as fast as I can.

I was thinking about your Twitter thread, in which you relate more details of what you were sketching at the bus station in McAllen, Texas, and in the immigration courts in Texas. Let me just read this one thing you wrote: “At a bus station where I met immigrant families who had just been released from these processing centers. So many moms asked me to borrow lipstick and eye pencil just to be able to look and feel like themselves again.” I found that really striking. You met these families that had just been released by ICE? What did they tell you about the detention centers where they’d been?

Immigrants nickname the Customs and Border Patrol processing centers “hieleras” (icebox) because they’re so cold. This is where immigrants are first held when they’re caught by Customs and Border Patrol and they might be held there for up to eight days, I heard. Then immigrants are either released or they’re turned over to ICE to be put in longer-term detention center, which is basically the same as a prison.

These immigrants were families with young children who had just been raised from the hieleras. They painted this picture for me of rooms that were so crowded that not everyone could lie down at once. They are not permitted to bathe except for maybe like once or twice in eight days and they’re not permitted to brush their teeth except when they’re in the showers and the Customs and Border Patrol also throw out people’s possessions on the pretext that maybe they’re smuggling drugs or something. It’s an incredibly miserable, degrading and demeaning and dehumanizing experience.

Related: At the US-Mexico border, migrants face an uncertain wait

From the bus station where these migrants have been dropped off, do they have the money, the resources to buy tickets for them and their kids? Where will they go? What do their futures look like?

There’s actually an intermediate step between getting out of the hielera and going to the bus station and that is that these people go to Catholic Charities. Catholic Charities has a shelter. They let people take showers, get a nap. They get some new clothing, get some toys for their kids and the Catholic Charities helps them get the bus tickets. Most of these people have family members in the US and they’re going to stay with their whatever relatives and most of them have also — most of the parents, I should say — also have been fitted with very large ankle monitors.

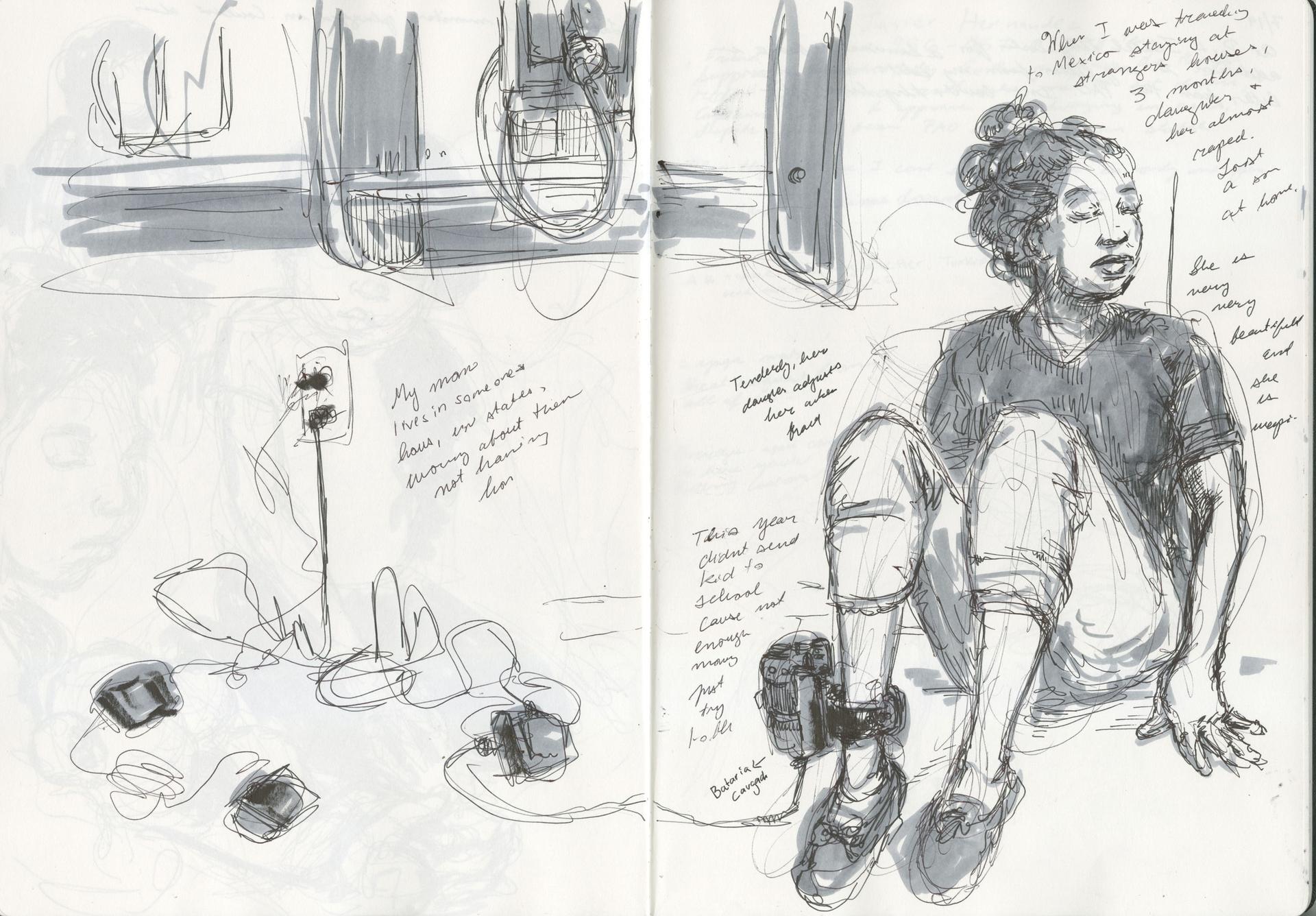

I want you to talk about another really arresting drawing you did at the McAllen bus station. It’s of a Honduran mother tethered to the wall by her plugged-in ankle bracelet. Tell us about this woman and the image, including what you wrote about it.

One of the things I think that many people don’t realize about ankle monitors, who perhaps have never worn one or seen one, is how large they are. But they also need to be plugged into the wall every 12 hours for some models of them, which is that you have to sit literally tethered to the wall like some sort of ball and shackle until this monitor beeps and tells you that it’s charged. These women are not criminals. These women are waiting for asylum cases. They’re not accused of any crime whatsoever. They’re not people who are out on bail. They are people who are claiming asylum, who consider themselves refugees. And we put these ankle monitors on them that are painful, that are intrusive and above all, that are stigmatizing. I don’t know any country in the world that does this with asylum-seekers except America.

Related: US officials reject blame for migrant girl’s death. Advocates point to Trump’s asylum policies.

I was looking at some of the comments in your Twitter thread and a few suggested that they came from people who saw your work and it seemed had suddenly found that empathetic nerve that allowed them to feel what these migrants are going through. Do you feel like your work is making a difference?

I think it’s never something that an artist or writer should say if their own work is making a difference. That’s sort of for the audience to say. However, I do think that because drawing is so obviously done with people’s hands so it’s so different from something that’s mediated with a machine like photography is, I think often that sort of evident labor can make viewers feel more empathy with your subjects.

Editor’s note: This interview has condensed and edited for clarity.